It’s a poem, a song, a history across geographies. The Lisette Project uses it to explore questions of political power and cultural equity.

An enduring song that’s part of ‘a fabulous, curious, and sometimes problematic mishmash’ of cultures on both sides of the Atlantic

The poem “Lisette quitté la plaine,” the oldest known Haitian Creole text, is a love story told from the perspective of an enslaved African man. He laments the loss of his beloved Lisette, who has left “La plaine,” a region of colonial Saint-Domingue (modern-day Haiti), sold to another plantation or sent into domestic service. For members of the Lisette Project team, the poem has become a lens to view wide-ranging musical, social, and political histories and their enduring implications.

The Lisette Project explores the performance history of this poem in song, while the project’s website — lisetteproject.org — offers scholarship and performance resources that help put the text and its cultural background in historical context. The project was originally funded by a Mellon Grant that founder baritone Jean Bernard Cerin and colleagues received while Cerin was on the faculty at Lincoln University, one of the oldest HBCU’s in the U.S.

The poem was written around 1757 by Duvivier de la Mahautière, a white colonist in Saint-Domingue. Using the still-developing Creole language, de la Mahautière structured his poem to be sung to the popular French tune of “Que ne suis-je la fougère.”

With de la Mahautière’s new text, the song was popular among the white elites and the middle class in Saint-Domingue. It eventually traveled across the Atlantic to mainland France and later crossed again to the United States. Today, the numerous musical versions of “Lisette quitté la plaine” serve as a reminder of the zig-zagging historical connections between these three countries, connections that remain unknown to many Americans.

‘No one talks about Haiti’

Haitian history has never been in the mainstream of American consciousness, yet this history is central to appreciating the work of the Lisette Project. Slowly, from different directions, this might be starting to change.

The New York Times, in its substantial, nine-story Haiti ‘Ransom’ Project — published in 2022 in English, French, and Haitian Creole — describes an 18th-century Saint-Domingue with a glistening arts and culture sector: “During slavery, Haiti brimmed with such wealth that its largest and most important city, Cap-Français, was known as the ‘Paris of the Antilles,’ bursting with bookstores, cafes, gardens, elegant public squares and bubbling fountains.”

A recent episode of SalonEra, an online series from the early-music ensemble Les Délices, was devoted to work by the Lisette Project and collaborators. Among the performers and scholars was musicologist Henry Stoll: “If it existed in France, they probably had it in Saint-Domingue.” By some estimates, Stoll adds, there were more opera performances per capita in Saint-Domingue than there were in Paris.

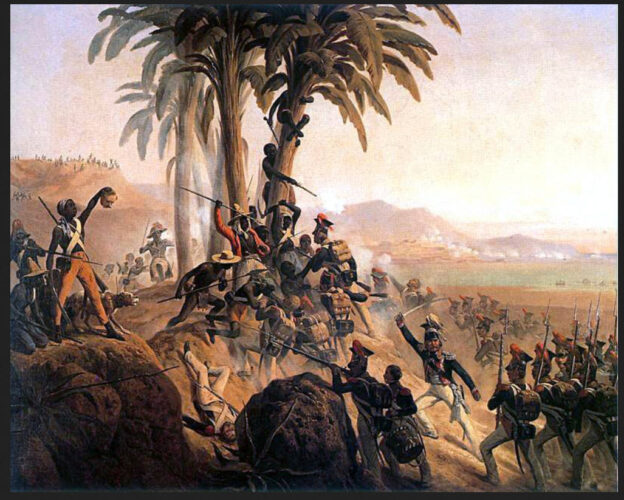

The wealth that fueled Baroque flourishings in France and its island colony was enriched by what scholars consider to be the most brutal slave economy in the Americas, driven by sugar and coffee cultivation. About 90 percent of Saint Domingue’s population was enslaved, controlled by a minority that maintained its power through the most inhumane of tactics. In 1791, members of the enslaved majority launched the first successful slave revolt in modern history. In 1804 they formed the independent nation of Haiti.

However, they had been made to pay for their freedom — a ransom at gunpoint for their independence. In 1825, France confronted the Haitian government with a devastating ultimatum: Pay massive reparations to Haiti’s former colonizers and slave owners, or go to war. With no allies, the self-emancipated nation chose the former solution and was forced to borrow exorbitant sums from French and later U.S. banks to repay these “loans” as well as the high interest and perennial late fees. Instead of investing in its own people and infrastructure, Haiti was still paying off its massive “double debt” until 1957.

As lenders in France and the U.S. built their own wealth, Haiti’s debt, as the Times reports, “cemented [its] path into poverty and underdevelopment.” In 2003, as Haitian President Jean-Bertrand Aristide demanded that France pay reparations back to Haiti, France and the U.S. joined forces to see him removed from power.

‘Mon perdi bonher à moué’

This turbulent, painful history leaves its imprint on how today’s audiences experience “Lisette quitté la plaine,” in all of its musical iterations. De la Mahautière’s original text appears here in Haitian Creole alongside Jean Bernard Cerin’s English translation:

| Lisette quitté la plaine, Mon perdi bonher à moué Gié à moin semblé fontaine Dipi mon pas miré toué. Le jour quand mon coupé canne, Mon songé zamour à moué ; La nuit quand mon dans cabane Dans dromi mon quimbé toué Si to allé à la ville, Ta trouvé geine Candio Qui gagné pour tromper fille Bouche doux passé sirop. To va crer yo bin sincère Pendant quior yo coquin tro ; C’est Serpent qui contrefaire Crié Rat, pour tromper yo. Dipi mon perdi Lisette, Mon pas touchié Calinda Mon quitté Bram-bram sonnette. Mon pas batte Bamboula Quand mon contré laut’ négresse, Mon pas gagné gié pou li ; Mon pas souchié travail pièce Tout qui chose a moin mouri. Mon maigre tant com’ gnon souche Jambe à moin tant comme roseau ; Mangé na pas doux dans bouche, Tafia même c’est comme dyo Quand mon songé, toué Lisette Dyo toujour dans jié moin. Magner mion vini trop bête A force chagrin magné moin. Liset’ mon tandé nouvelle To compté bintôt tourné : Vini donc toujours fidelle. Miré bon passé tandé. N’a pas tardé davantage To fair moin assez chagrin, Mon tant com’ zozo dans cage, Quand yo fair li mouri faim. | Lisette has left the plain I have lost my joy. My eyes look like fountains Since I last saw you. By day, when I cut sugar cane, I miss my beloved; By night when I lay in bed, In sleep I hold you. If you go to the city, You’ll find young dandies Who deceive women With their mouths sweeter than syrup You’ll think they are sincere While they are very cunning They are deceptive serpents Who cry “Rat” to deceive them. Since I lost Lisette, I haven’t touched the calinda I have left the Bram-bram sonnette I haven’t beat the bamboula When I meet other women They do not catch my eye. I do not care about work All that mattered to me has died. I am skinny as a stem My leg is like a reed Food is not sweet to my mouth Booze is like water. When I think of you Lisette Tears fill my eyes. My manners have become stupid From the force of my despair. Lisette I heard news You intend to return soon Come then still faithful. Seeing is better than hearing. Delay no more You’ve made me sad enough I am like a bird stuck in a cage When they starve it to death. |

The Lisette Project’s work includes a short documentary by filmmaker Brandi Berry and a lecture-recital, which focuses on the following five musical versions:

–The first known musical setting of the poem, which the French colonist de la Mahautière set to the popular French tune “Que ne suis-je la fougère,” circa 1757.

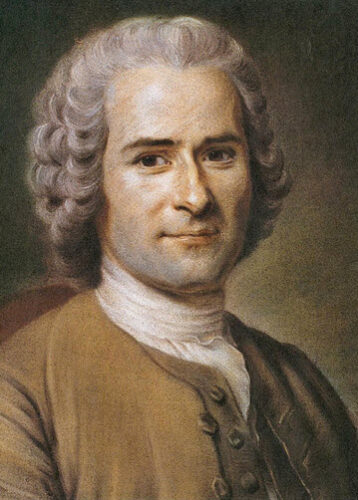

–A new setting of the same story, “Chanson Nègre,” composed in France by the influential philosopher (and composer) Jean-Jacques Rousseau, with words by the Chevalier de Flamanville, 1778.

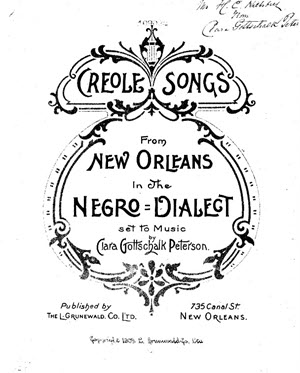

–A new setting titled “Zélim to quitté la plaine,” with words and music by Philadelphia composer and pianist Clara Gottschalk Peterson, published in her 1902 anthology Creole Songs from New Orleans in the Negro Dialect.

–A 1920 setting titled “Lisette” by Haitian pianist and composer Ludovic Lamothe. Lamothe’s version incorporates méringue, a traditional Haitian dance form.

–A 1942 arrangement, “Lisette, ma chère amie,” by composer, pianist, singer, and ethnographer Camille Nickerson. This setting combines Peterson’s 1902 tune and a text that is close to the original poem.

Connect the dots

The first version to come to Cerin’s attention was not the original, but rather the 1942 Louisiana folk song by Camille Nickerson. Cerin, who grew up in Port-au-Prince and Philadelphia, returned to Philadelphia after completing his graduate studies. In 2019 a local artist asked him to curate a concert to accompany an exhibition that, as Cerin describes it, “explored the relationship between Louisiana, Philadelphia, and Haiti.” He sang Nickerson’s setting on that program.

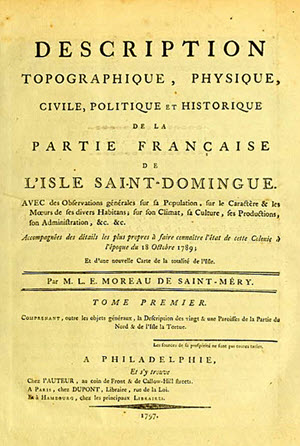

In his research, he also came across a history book about Saint-Domingue written in Philadelphia in 1797. The book, Description topographique, physique, civile, politique et historique de la partie française de l’isle Saint-Domingue, includes the original song text “Lisette quitté la plaine” and notes that it was sung to the tune “Que ne suis-je la fougère.” Cerin recognized the poem from the Nickerson song, got his hands on the tune, and found that the poem did indeed fit the melody.

Yet no mention of the original Saint-Domingue version of “Lisette quitté la plaine” was made in the literature that Cerin first encountered when he studied Louisiana folk songs. This reflects the siloed nature of existing scholarship related to the poem. “Literary historians engaged with the text, but not with the music,” Cerin says. “People studying the poem in Haiti don’t engage with the fact that it ends up in Louisiana, and people writing about Louisiana don’t engage with the fact that the poem is from Haiti.”

By making the performance history of “Lisette quitté la plaine” the focal point of the Lisette Project, Cerin saw an opportunity for music to connect the dots between studies in disparate fields. He began reaching out to potential collaborators across disciplines and throughout North America.

After this initial excitement, Cerin hit pause. Studying historical sources is one thing; performing them is another. He quickly found himself confronting challenging questions.

“‘Lisette quitté la plaine’ is a slave narrative written by someone who could have been a slave owner,” says Cerin, “and it was popular among slave owners.” At the same time, he acknowledges that “just because that was the case doesn’t mean that enslaved people couldn’t have sung it or that it didn’t come from them in the first place.”

Several references to Africanisms in “Lisette quitté la plaine” — such as the bamboula instrument or the calinda dance — give reason to question whether “Lisette quitté la plaine” might also have unexplored origins among Saint-Domingue’s African-descended population.

‘Oh, this is a pastoral!’

In a recent conversation, SalonEra musicologist Stoll noted that such references offer “a precious glimpse into the rich and diverse musical practices that flourished among Saint-Domingue’s enslaved population. Not only do they show the prevalence of West African musical traditions in the colony, but they also show the importance of these traditions in the development of what would become Haitian music.”

Stoll continues, “They also suggest that — despite the colonial administration’s efforts to proscribe drumming, dancing, and other forms of African musical expression — French colonists were not wholly ignorant of the musical worlds around them. In fact, several of their songs and operas show a certain indebtedness to the cultures of the colony’s African majority.”

The musical interconnectivity among social classes in the 18th-century colonial Caribbean context that musicologist Maria Ryan describes in SalonEra’s Finding Lisette episode further strengthens the case for “Lisette quitté la plaine” having possible undocumented African origins: “People lived in close quarters,” Ryan explains. “There was segregation to an extent, of course, but there are lots of accounts of boys in the field whistling Handel with accuracy or the circulation of tunes beyond where they were intended or where listening was even anticipated.”

When Cerin first brought “Lisette quitté la plaine” to the attention of Baroque oboist Debra Nagy, artistic director of Les Dèlices, her immediate reaction to the text was “Oh, this is a pastoral!” — a popular 18th-century literary genre in which a man of low social status can’t be with the woman he loves because of external social forces out of their control. This reimagining of the European pastoral in the Haitian context, combined with possible African origins, make the first documented song in Haitian Creole, as Cerin puts it, “a creole — or a mixture — itself.”

It is this multifaceted history of “Lisette quitté la plaine” that makes Cerin feel empowered to bring this song from the archive to the stage: “What is powerful about ‘Lisette quitté la plaine,’” he says, “is its enduring presence over time, coupled with changes in the people who set the text, their motivations in setting it, and changes in who was listening to it.”

‘We have to ask ourselves why Haiti has been left out of the Enlightenment narrative.’

Cerin has performed “Lisette quitté la plaine” on the Lisette Project’s lecture-recital at universities and festivals around the country, sometimes joined by sopranos Michele Kennedy or Melissa Joseph. The performance is often coupled with a showing of the Lisette Project’s short documentary. In addition to the five above-mentioned versions of “Lisette quitté la plaine,” the program includes pieces contemporary to each version that explore complementary ideas. Many of these ideas engage with ever-debatable elements of Enlightenment thought.

“Using music to situate Haiti within our understanding of the Enlightenment has become a central goal of the project,” says Cerin. “We have to ask ourselves why Haiti has been left out of the Enlightenment narrative. The questions that Enlightenment philosophers are engaging with — in terms of who is human, who is not, what is a man, what is a citizen — are being engaged with in Haiti. But in Haiti they’re going one step further.”

Cerin explains, “In the first Haitian constitution, all citizens are black, as a legal designation, not a ‘scientific’ one. The word for man in Creole is ‘nèg.’ Where I am from, a white man is a ‘nèg.’ They were intentionally claiming the word to just mean human. Having been enslaved, they were aware of the shortcomings of Enlightenment philosophy, that it wasn’t going far enough.”

In curating the concert program to foreground this context, Nicholas Mathew, one of Cerin’s collaborators on keyboard, believes that audiences “stand a better chance of hearing music as it really was and is: a fabulous, curious, and sometimes problematic mishmash.”

Mathew describes the lecture-recital as “a compelling paradigm for how to engage with what may be unfamiliar music,” noting that, “Cerin always tells the audience where the music came from, how it came to be in front of them, who put the effort in to make and remake it, and how it is entangled with all the other music that they have just heard. It helps, of course, that the music is pretty easy to love!”

Soprano Michele Kennedy says she loves the “Lisette” program, not least because she knows it’s entirely new music to audiences: “It is at times very playful, flirty, and fun and, at other times, it branches into tales of enslaved people, class struggles, and searing social commentary.”

Feeling the power of programming these songs, she continues, “is not only an intimate musical experience, but one that can vivify and humanize a group of people whose stories have been long neglected in our American history lessons. In bringing this repertoire to the stage we are centering Haitian classical music in the wider musical canon. It is high time that these important songs are more widely known. And, not least, the music is deeply affecting and absolutely beautiful!”

In the fall of 2023, Cerin will begin a new post as director of the vocal program at Cornell University, which comes with research funds to help expand the Lisette Project. His hope is for long university residencies, where he can work with voice students on repertoire from Haiti and the Haitian diaspora.

“There are many very uncomfortable aspects of our history that come to the surface very quickly when you engage with colonial music,” Cerin says. “A lot of that uncomfortable stuff can be the solution to the history that we’re trying to unpack today. In that way, early music can be the antidote.”

Ashley Mulcahy is a Boston-based mezzo-soprano and graduate of the Voxtet Program at the Yale School of Music and Institute of Sacred Music. She sings with numerous ensembles and co-directs her own voice and viol ensemble, Lyracle. For EMA, she’s recently written about children learning to play the viola da gamba in Texas.