Cover Article in the May 2020 issue of EMAg, the Magazine of Early Music America

In this and coming issues, EMAg will feature makers of early-music instruments, celebrating artisans who design and craft wind, string, keyboard, and percussion instruments based on historical models. Some of these makers are players themselves, and all interact closely with those who collect, play, and love their instruments.

Current EMA members and EMAg subscribers can join the discussion below!

Whether playing our modern horns or their ancestors, we brass players like nothing more than to talk shop and compare equipment. How does one make or model of horn “play” compared to another? Does this mouthpiece give me a darker or brighter sound? Is that a custom build? With replicas of historical instruments, the questions tend to extend into building techniques: Is the bell hand-hammered? Are the tubes rolled or drawn? Are the sections of the instrument friction-fit or soldered? Which metal percentages were used in that alloy? Does the mouthpiece have a flat rim and sharp grain?

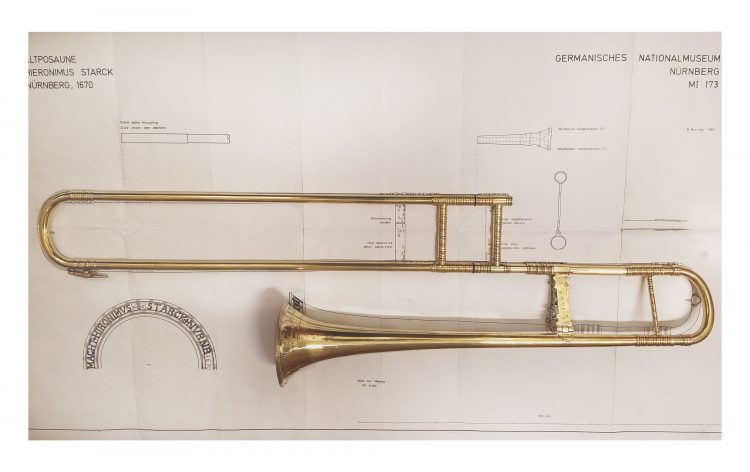

Fundamentally, these questions ask about the instrument’s fidelity to a historical model: Is the instrument I play made with the same attention to historical building techniques as the attention I attempt towards historically informed performance while playing it? After all, replicating instruments of the past is just as much a component of historically informed performance as is using those instruments to revive the music they were intended to play. (Special mention must be made of the work and research in this domain—the replication of historical instruments as a form of performance practice—of Robert Barclay, whose research may be found in The Art of the Trumpet-Maker: The Materials, Tools, and Techniques of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries in Nuremberg.)

The question of authenticity—that increasingly taboo buzzword—is complicated and certainly misleading. Although we indeed have original, authentic instruments from the past, the earlier in time we move, the more difficult it is to know exactly which quality of sound was most highly esteemed (and by whom?), and writings on technique become more vague and scarce. This relative paucity of source materials has led to several camps of building and playing preferences in the modern revival of early brass instruments and performance practices. Some builders and players opt for the familiarity and comfort of an instrument and setup (mouthpiece, embouchure, etc.) that produces a sound more immediately pleasing to modern ears. Others favor an instrument that is as faithful as possible in its construction to its model, but does the sound quality suffer? And to whose ears? The question of instruments and historical fidelity is thus particularly complex due to contrasting points of view.

The goal of this article is not to decide which instruments are “the best,” nor to qualify the plethora of instruments available, but rather to consider what we look for in an instrument, why we play the particular instruments we do, and what we can (or cannot) learn from these instruments. The article encourages a dialogue about original historical brass instruments and their replicas with the craftspeople in (or from) North America who make and restore those instruments. Let’s talk shop with the people in the shop!

One of the main challenges many of us in the world of early brass playing face is that we must be literate and proficient in several centuries’ worth of music, musical styles, and performance practices. Having the correct equipment or tools is essential to even being able to partake in music-making with others, especially with questions of historical era and pitch. For example, if I were

to arrive at a rehearsal of 16th-century music where the ensemble pitch is a’ = 465hz with a German Romantic trombone pitched at a’ = +/- 438hz, I would be hard-pressed to finesse the instrument’s sound to blend with the ensemble, let alone play in tune with a half-step transposition. And it would be even more difficult, if at all possible, for a horn player with a modern replica of a baroque horn at a’ = 440hz to take part in a performance with a baroque orchestra tuned to a’ = 415hz. Even if the orchestra were playing a composition in F major, the horn would have to be crooked to E, but temperaments of the period dictate that the 415 F be tuned significantly higher respective to the 440 E.

Several of the instrument makers with whom I spoke said they began replicating historical instruments out of a need to have a proper instrument for a particular job. Historical horn maker Richard Seraphinoff, professor of music in horn and natural horn at the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, elucidated on this point: “In the mid-1970s, when I began studying natural horn with Lowell Greer, there were very few accurate copies of natural horns being made. The only choices were antique instruments, which were prohibitively expensive for a student, and almost no makers had begun making natural horns whose dimensions were copied precisely from original horns, or whose methods of construction were those of the 18th- and 19th-century makers. The initial attraction was that Lowell and I were invited to play with the Ars Musica Baroque Orchestra in Ann Arbor, MI, and we needed horns. The first instruments that we made together in Lowell’s workshop were made of modern horn parts, and it took the next 30 years of research, experimentation, and playing on the instruments I made in performances to arrive at the point where I was making copies of baroque and classical horns with dimensions, materials, and techniques that were true to specific originals in museums and private collections.”

It is great to be able to tell students about how much there is to work towards, both technically and musically, before we necessarily find the best instrument for the proper repertoire. There is so much we can learn about the performance practices for music of the Middle Ages, Renaissance, Baroque, Classical, and Romantic eras, such as phrasing, articulation, and sound concept. Although proficiency in these parameters can, in turn, inform our equipment selection, the fact of the matter is that we may only develop these playing techniques so far unless we are using the proper tools. In addition to learning about a particular style of music and how to play it, we can additionally learn from the instrument. As historical trumpet and trombone maker and player Nathaniel Wood has written of the demands he imposes upon his own craftsmanship, “My aim is that every instrument to leave my atelier will be not only a fine tool for the highest level of musicmaking, but also a good and demanding teacher.”

This is especially pertinent when it comes to sound concept. Seraphinoff spoke to this point. “The instruments taught me a lot about how to play the music. For example, many of us played Haydn symphonies for many years on French, early 19th-century instruments, which produce a round, full sound and were meant to be played in a larger orchestra. When I started making a copy of a Viennese instrument made in 1760, all of a sudden the more compact sound balanced better in a Haydn-sized orchestra of 15-20 players, the upper range was more accessible and secure, and the sound the horn produced gave a completely different feel to the wind section than we had previously heard from the larger 19th-century instrument. Copying many historical mouthpieces has also given me a lot of insights into the true sound of the baroque and classical horn.”

This is especially pertinent when it comes to sound concept. Seraphinoff spoke to this point. “The instruments taught me a lot about how to play the music. For example, many of us played Haydn symphonies for many years on French, early 19th-century instruments, which produce a round, full sound and were meant to be played in a larger orchestra. When I started making a copy of a Viennese instrument made in 1760, all of a sudden the more compact sound balanced better in a Haydn-sized orchestra of 15-20 players, the upper range was more accessible and secure, and the sound the horn produced gave a completely different feel to the wind section than we had previously heard from the larger 19th-century instrument. Copying many historical mouthpieces has also given me a lot of insights into the true sound of the baroque and classical horn.”

Greer, fellow historical-horn maker and player with whom Seraphinoff began building instruments, said of hearing an instrument that sounds out of place within a particular ensemble, “Unfortunately, we hear a lot of recordings where the horns sound quite modern. It’s not unusual to hear Baroque music from the 1740s played on 1850s French opera horns, played well but with the wrong aesthetic…I think in brass the people who hire are very undiscerning. Truly he or she may be a master player, but if they’re not equipped properly, it’s void.”

Beyond having the right instrument for the right job is the question of compromise. Across the board, the instrument makers with whom I spoke agreed that modern compromises can hinder players from having a better understanding of historical performance practices. According to trombonist Brad Close, a sackbut maker and owner of the Brass Medic, an instrument repair shop in La Crescenta, CA, “I think what is and isn’t possible on the instrument influences the style with which you play it. If you are playing an instrument that is modernized in some way, you will be lacking an element of understanding. But if a convenience can be added with minimal effect on authenticity, then the advantage gained can outweigh the disadvantage. I think every player has to decide for him/herself where the line should be drawn.” Typically, the cheaper the instrument, the more modern compromises it presents.

There was a consensus among the makers that “budget” instruments have their place—that, as serviceable instruments they serve the purpose of helping the student or amateur new to early brass start down the HIP path towards music that interests them. According to Seraphinoff, “If an amateur player or student can’t afford a hand-made, historically accurate instrument, rather than not have the experience of playing without valves, getting to know how to make music with a single overtone series, or learning the art of hand stopping, I would rather that they play on a less authentic instrument and learn those things.”

“On the other hand,” says Wood, “these mid-priced instruments also tend to make more compromises toward modern players’ expectations, and do not adequately encourage the player to approach the historical instrument in a meaningfully different way from a modern horn.”

Such modern affordances give players a false sense of what historical brass playing is all about. One prime example of this is the addition of vent holes on replicas of baroque trumpets and horns. “The trumpet and horn with holes have given us a faulty impression of the way they actually sounded,” Seraphinoff says, “and as more players devote more time to practicing the early 18th-century horn or trumpet without holes, they are able to perform successfully on them, and the listener experiences an entirely different feel for what the composer had in mind and what the instruments were expressing.”

Trumpet maker and player Nikolai Mänttäri Morales, who opened his workshop in Orlando, FL, in 2019, emphasizes the time investment required to master a truly natural trumpet, saying it took him five years to develop his embouchure to the point where he could play decently in the clarino register. He admitted to his initial frustration: “I could play everything on piccolo [trumpet], but suddenly could not play the most basic of tunes on natural trumpet.” He persevered, letting the instrument be his teacher, and the work paid off in the “golden” quality of sound alone, one featuring “a little fuzz” that is “not as pure or clean; it fits descriptions of how you would describe Baroque art.” It also accords with the grainier, raw sound quality of gut strings, for example. But it took a modern feature such as vent holes to help find and appreciate this “golden” baroque sound. “I think it has been a necessary step in the development of the early brass world,” Seraphinoff says, “and we’ll see in the next few years if we are beginning to transcend it and make playing without holes more the norm.”

Compromises work in both directions, though. Consider a historical compromise of a modern instrument: In an effort to lend a more historical sound to the low brass of early 19th-century wind ensembles, serpentist and ophicleidist Craig Kridel commissioned a mouthpiece—named for the late serpent maker Keith Rogers—that yielded the sound of a serpent on the euphonium. “The Rogers mouthpiece was designed for early 19th-century Harmoniemusik, and while we would have liked to insist that this music must be performed on authentic instruments, we knew we were outsiders talking to well-meaning modern instrumentalists who were either going to cut the lines or score them for tuba/euphonium,” said Kridel. “The mouthpiece permits the euphonium to blend with the bassoons, which was the purpose of the serpent and English bass horn. At least it mollified a dreadful performance practice that was in use and, with our presentations, introduced some sense of historical perspective and the quest for a more authentic sound for our modern-instrument colleagues. We would never consider a mouthpiece to help replicate the sound of an ophicleide. That is a skill that we wish to expect from today’s modern tubist [i.e., to play the ophicleide]. But we felt we could compromise with the serpent.”

Players interested in 19th-century repertoire and instruments may still find ophicleides and other Romantic- and Civil War-era originals, which survive in various states of repair. To this end, I asked Robb Stewart of Southern California about his work restoring antique brass instruments. “For repair of historically important instruments, the more important issue is preservation. I have put much effort into practices that avoid making changes that are not reversible,” he says. For such instruments, “I generally refuse to modify the original. There may be cases where a device can be added which is completely removable and I may or may not agree to that. As I got older, I would refuse to make modifications even on more modern instruments if I thought it was a waste of money and effort.” He further warns, “Unfortunately, the state of the art in the repair business is to make instruments appear to be in better condition as cheaply as possible. When rare antiques are subjected to this, they suffer much damage that can’t be reversed, such as removing metal by filing, sanding, and polishing and discarding original parts.”

The goal of every instrument maker I spoke with is to deliver an instrument that serves the music for which it was intended as faithfully as possible. This involves various degrees of commitment, both to the instruments and to the music, on the player’s part. For horn maker and player Andrew Clark, “After more than three decades of performing on historical horns—both originals and reproductions—and taking careful note of their dimensions, characteristics, and sound, I came to the conclusion that what needs to be served by the instrument maker are the needs of the performer in giving the audiences a satisfying entertainment…My instruments therefore aim to embody the design ethos and sound world of historical models, but as far as possible give good intonation and ergonomic handling. I don’t claim to make exact replicas, but I do try to supply instruments that work really well for the performer.”

The goal of every instrument maker I spoke with is to deliver an instrument that serves the music for which it was intended as faithfully as possible. This involves various degrees of commitment, both to the instruments and to the music, on the player’s part. For horn maker and player Andrew Clark, “After more than three decades of performing on historical horns—both originals and reproductions—and taking careful note of their dimensions, characteristics, and sound, I came to the conclusion that what needs to be served by the instrument maker are the needs of the performer in giving the audiences a satisfying entertainment…My instruments therefore aim to embody the design ethos and sound world of historical models, but as far as possible give good intonation and ergonomic handling. I don’t claim to make exact replicas, but I do try to supply instruments that work really well for the performer.”

There are certainly more historically steadfast makers, however, who would be more hesitant to comply with certain desires or refuse outright, as in Wood’s case: “Ultimately, it doesn’t interest me to build instruments I don’t believe could have existed historically…I am convinced that the tools we choose to use in our musicking inform how we play. And I’m furthermore convinced that, partly because the instruments help us to develop an instinct for historical repertoire and partly thanks to the differences in sound, articulation, etc., performances on instruments that are as close as possible to those of the period are more effective. The music speaks more naturally and eloquently in the ‘voices’ which were known when it was composed.”

So, when the time comes to invest in a new instrument, what will you look for? What might one instrument be able to teach you over another? Most of us strive to learn as much as possible about the music of the past and how to perform it, and shouldn’t our instrument(s) and our medium of musical expression aid us in this endeavor? As Greer said of his own workmanship, “I tried to act as a puppet to the anonymous Bohemian master who made the instruments. I never found his shop but continued to follow his precepts.”

Short of having a time machine, we may never find the shop, but the original instruments that these historical instrument makers have left as breadcrumbs scattered over time have certainly led modern makers and restorers in the right direction. It’s up to us to follow their lead.

Adam Bregman plays historical trombones from every era, with a special interest in Medieval, Renaissance, and early Baroque repertories. He leads the annual Indiana Sackbut Workshop, teaches early brass at the San Francisco Early Music Society Medieval & Renaissance Workshop, and is pursuing a Ph.D. in historical musicology at the University of Southern California.

Adam Bregman plays historical trombones from every era, with a special interest in Medieval, Renaissance, and early Baroque repertories. He leads the annual Indiana Sackbut Workshop, teaches early brass at the San Francisco Early Music Society Medieval & Renaissance Workshop, and is pursuing a Ph.D. in historical musicology at the University of Southern California.

Your Input is Instrumental

Questions facing both players and makers are potentially fascinating. Therefore, beyond merely profiling makers of historical instruments, we would like to pose some of the following:

- To what extent is your work historically informed, and where do you part company with your historical counterparts to make your instruments work in the modern world?

- For whom do you make your instruments, and how does that affect your choices?

- What have you learned along the way that has changed your approach?

- What information would you most like to share with modern players of your instruments?

- What questions about your instruments and those of the past keep you up at night?

Because players perform such an important role in this discussion, we would also like to hear about their insights into the marriage between historical instruments and performance practices. Finally, to all of our readers, your questions and comments can inform us as we interview makers and players around the country. To that end, we invite you to share you questions or comments in the discussion below.