One of the earliest known mixed-race composers of African descent, Lusitano writes in an opulent, richly detailed style that reaches the realms of the ecstatic.

‘An Exercise in the Pleasure of Singing’

“There was electricity in their applause,” recalls Malcolm J. Merriweather, music director of New York’s Dessoff Choirs, about audience response at a 2022 concert of motets by African-Portuguese composer Vicente Lusitano.

“They were impressed by the grandeur of the music. They were captivated by Lusitano’s unique voice.”

Such reactions to Lusitano’s music have been dormant for nearly 500 years. Prominent histories of European music have mostly, or entirely, ignored the compelling biography of Vicente Lusitano. The composer was never wholly forgotten, at least among specialists in Renaissance music. But these sources discussed Lusitano in relation to a notorious dispute which he won, then lost, but is now winning again.

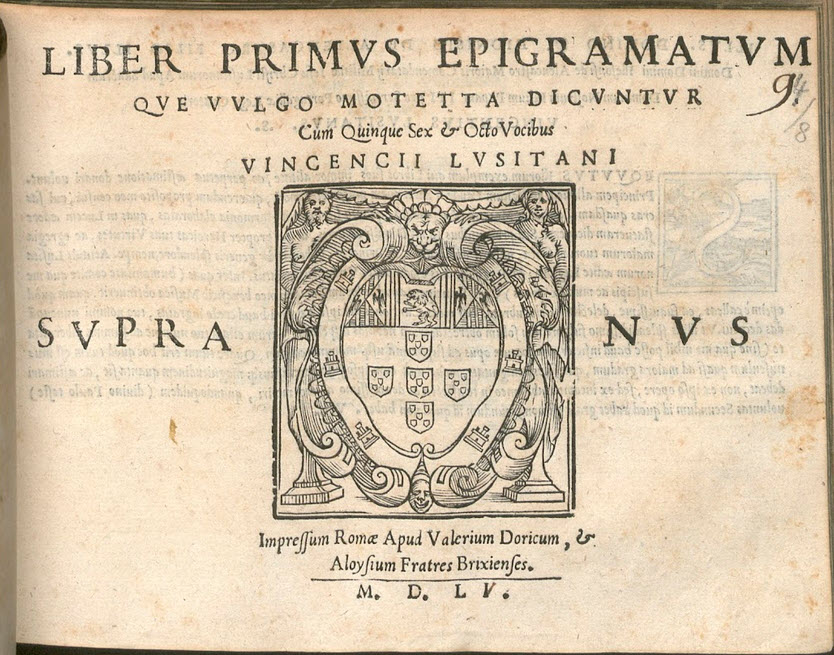

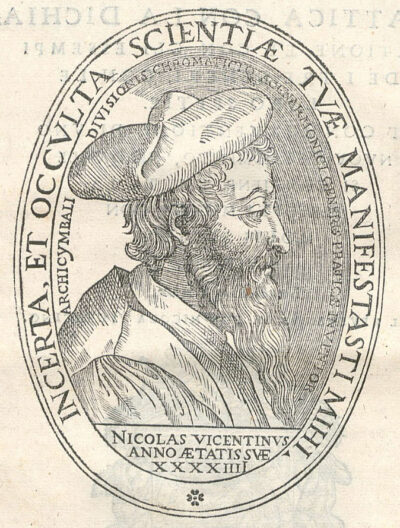

We can start in the most impactful year of Lusitano’s life, 1551, when he published a motet collection, Liber primus epigramatum, and defeated Nicola Vicentino (1511-c.1576) in the infamous debate, which involved conflicting definitions of mixed genus music. These events were connected, as Vicentino challenged Lusitano following a performance of Lusitano’s motet “Regina caeli” at the end of May 1551.

Over the next two weeks, a panel of three expert Vatican musicians — Bartolomé de Escobedo, Giulio D’Arezzo, and Ghiselin Danckerts — presided over the debate, convening the two composers for a series of formalized oral arguments that culminated with written testimony.

The dispute arose from Vicentino’s provocative notion that composers of the day did not understand the genera they used in their own music. Vicentino’s argument, which musicologist Giordano Mastrocola describes as “an ill-conceived syllogism,” claimed that any melodic motion by a major or minor third must be seen as a signal of mixed genus music because the diatonic genus’ tetrachord only contains whole and half steps.

Lusitano countered that singular melodic movements do not necessarily denote what Vicentino asserts. Because other distinguishing intervals of the chromatic and enharmonic genera (such as the diesis) did not appear in contemporaneous vocal music, Lusitano found Vicentino’s conclusions incongruous with common musical practice and thus dismissed them.

On Sunday, June 7, 1551, the Vatican experts ruled Lusitano the winner.

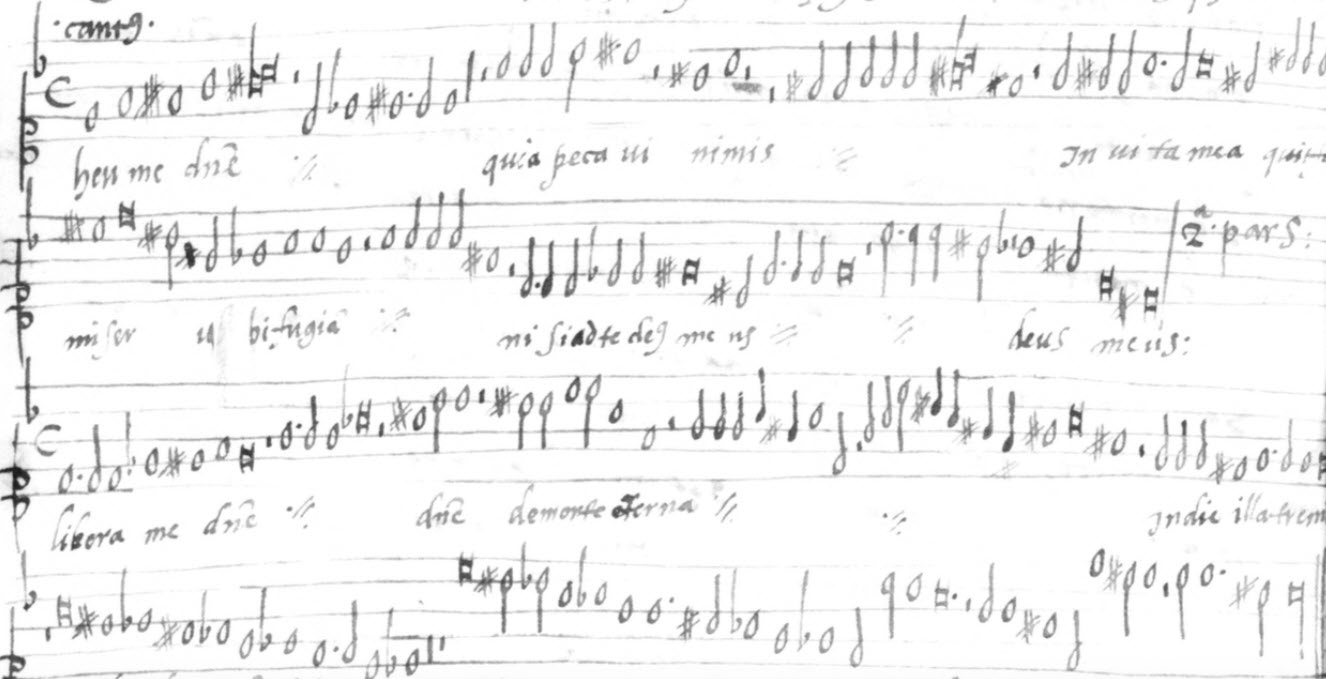

Yet his music wasn’t discussed in academic literature until the late 19th century, and only two of his works — the strikingly chromatic motet “Heu me domine” and the Italian madrigal “All’hor ch’ignuda” (1562) — appear on commercial recordings produced in the 20th century.

Before 2020, performances of Lusitano were rare. But the start of the global pandemic and the Black Lives Matter protests for George Floyd, a Black man murdered by police in Minneapolis, helped shift the cultural conversation.

Lusitano’s unique position — the only published composer of African descent in 16th-century Europe — meant early-music performers across the United States could use his music in response to these emergent social issues. While notated music by African composers pre-dates Lusitano’s career by hundreds of years, and paintings depict Black musicians and composers in Europe long before Lusitano, current scholarship suggests his polyphonic output stands alone in the history of Black classical music.

Lusitano was not the first published composer of African descent. Saint Yared, a 6th-century Ethiopian priest, wrote music and developed notation systems that survive to this day. Nor should Lusitano be billed as “the first composer of African descent in Europe” since the dark skin on the portrait of Lorenzo da Firenze (d. 1372 or 1373) in the Codex Squarcialupi suggests he may have been Black.

There are also written and other visual records of Black musicians performing in Europe before and during Lusitano’s lifetime. It’s plausible, perhaps likely, that some of these musicians created original music, even if there’s currently no documentation. (The term “composer” has a fluid meaning, depending on context.)

How and why did Lusitano fall into obscurity in the first place? There was no isolated incident but, rather, an iterative process facilitated by print technology over hundreds of years. From the 16th century onward, limited and sometimes inaccurate information about Lusitano was published and uncritically reproduced by the next generation of scholars, lending authenticity to errors and misunderstandings.

Lusitano, like other musicians from oppressed populations, was always more likely to slip into the shadow of “canon” composers. The history of the field we call “early music” is thoroughly entwined with the practices and profits from European colonialism and the forced diaspora of Africans around the world. And the traditions and biases of early music also intersect with the racism, sexism, and discriminatory culture of each society.

The history of the field we call ‘early music’ is thoroughly entwined with the practices and profits from European colonialism and the forced diaspora of Africans around the world.

But Lusitano’s racial identity is not the only reason his legacy was undervalued for so long. Misunderstanding and deliberate misinformation plagued Lusitano’s posthumous portrayal, which distorted the meaning of his writings, dampened interest in his biography, and even obscured the existence of his compositions. To understand the full story, we need to start at the beginning.

A Winning Debater

Vicente Lusitano was born in Olivença, now part of Spain, around 1522. Portuguese chronicler João Franco Barreto, in a 17th-century manuscript, offered the only known textual evidence of Lusitano’s heritage when he referred to the composer as “homem pardo.”

The word “pardo” first appears in 12th-century Portuguese texts as a descriptor of darkly colored objects, and later references dark fabrics. This meaning of “pardo” becomes racialized in the 14th and 15th centuries to designate mixed-race people of African descent whose skin color was considered ambiguous. Documentation of Lusitano’s mixed-race identity may be limited, but scholars have not found evidence to the contrary.

Many pieces of evidence further illuminate this understanding of Lusitano’s racialized identity. First, 16th-century Portugal had a significant Black population. Lusitano was born about 80 years after Portugal began importing enslaved Africans, and records show African and African-descended people represented up to four percent of Olivença’s population during his lifetime.

Second, Black musicians received musical training in Portugal during this era, for example, early 16th-century paintings depict Black shawm players performing in the Portuguese court. Finally, the Catholic Church’s professional restrictions targeting priests of African descent align with barriers Lusitano likely encountered in his career across Europe. He was ordained but never held a benefice, nor ever gained employment as a maestro di cappella in Portugal, Spain, or Italy.

This would be a curious oversight given Lusitano’s ability, publications, and reputation. But Pope Leo X had barred Black priests from such employment in 1518. It is plausible these professional limitations motivated Lusitano’s conversion to Protestantism and relocation to Germany in the early 1560s.

Prior to the summer of 1550, Lusitano appears to have entered into the service of Dom Alfonso de Lencastre, the Portuguese Ambassador to the Holy See. Lusitano’s Liber primus epigramatum (1551), his only known motet collection, is dedicated to Alfonso’s son, Dinis, and it is possible Dinis was Lusitano’s pupil. This connection helps explain how Lusitano traveled from Portugal to Rome, as the ambassador and his entourage, including Dinis, departed Lisbon on August 13, 1550, and presented their credentials to Pope Julius III on January 7, 1551.

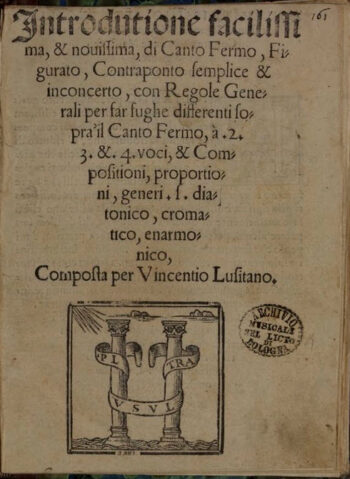

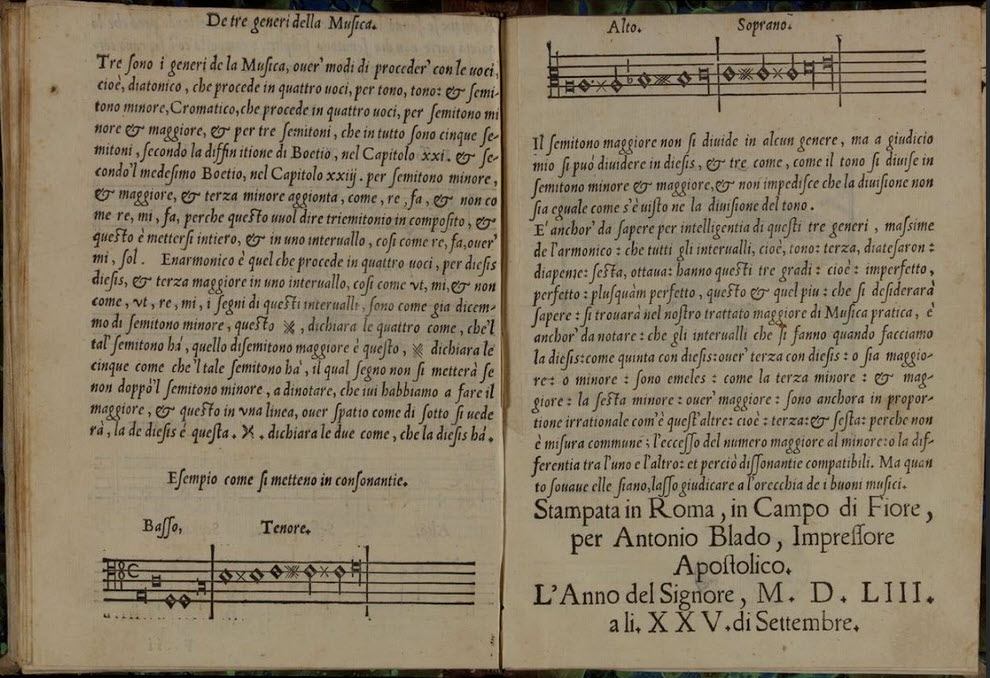

In 1553, two years after the debate with Vicentino and the Vatican experts’ decision, Lusitano published the first edition of his pedagogical composition manual, Introduttione facilissima, in Rome. Two subsequent editions were printed in Venice in 1558 and 1561, indicating that Lusitano was a successful teacher and that he moved to northern Italy sometime in the mid-1550s.

Correspondence shows Lusitano converted to Protestantism and married sometime before 1562, at which point he traveled to Stuttgart to audition, unsuccessfully, for a musical position at the court of Duke Christoph of Württemburg.

The known documentation recording Lusitano’s life ends here.

His manuscript treatise on improvisation and counterpoint, Tratado de canto de organo, was part of the private collection of poet Philippe Desportes (1546-1606), suggesting Lusitano also had connections to French artistic circles.

But soon after, the narratives that came to define Lusitano and his music stem from the 1551 dispute in the historical record, which were based on Vicentino’s personal, embittered account of the event, published in his 1555 treatise L’antica musica alla ridotta moderna prattica.

Here, Vicentino uses fabrications and an intentional misreading of Lusitano’s writings to discredit the African-Portuguese composer and render the debate’s outcome illegitimate. Despite the availability of contradictory evidence, Vicentino’s version of the debate proved persuasive to generations of historians. Lusitano became trapped as an ancillary, conservative and, most damning, uninteresting figure. Lusitano won the battle but lost his legacy.

Subsequent scholarship has also shown that many of the concepts Vicentino claims to have originated in L’antica musica are found in earlier texts from around Europe. Musicologist Giordano Mastrocola has noted precedents to both Lusitano and Vicentino’s discussion of melodic intervals in early 16th-century Iberian treatises as well as the work of 15th-century Italian theorist Florentius de Faxolis. Does this suggest Vicentino’s negative portrayal of Lusitano was part of a larger, exaggerated attempt to cast himself as an unparalleled innovator?

Black Lives Matter in Renaissance polyphony

In the last few years, not only have academics explored Lusitano’s biography in new ways, but an international cohort of musicians has amplified his legacy as a substantive composer.

The San Francisco-based vocal ensemble Chanticleer dove into Lusitano’s music at the onset of the current wave of interest. Tim Keeler, Chanticleer’s music director, joined the organization in March of 2020, and he “began to think about programming and composers that would fit” the awakened cultural mood. He credits conversations with Marques L.A. Garrett, who runs the University of Nebraska-Lincoln’s choral activities, as a start on the path toward Lusitano.

The world might have been ready to hear Lusitano, but resources on his life and output remained limited, making his music difficult to program. Keeler and his Chanticleer colleagues encountered these challenges first hand. In June 2020, IMSLP only offered a scan of the original edition of Lusitano’s substantial Liber primus collection. Fortunately, in a sense, pandemic disruptions meant Keeler had time to make these 16th-century partbooks compatible with Chanticleer’s 21st-century performance practice.

He recruited a Chanticleer baritone, Matthew Knickman, to make rough, full-score transcriptions of Lusitano’s motets. This enabled Keeler to assess the music and imagine how it could fit into Chanticleer’s programming. They settled on the motet “Ave spes nostra,” music that “suited the voice ranges of our ensemble,” Keeler observes. He calls it “a fun piece—although we couldn’t find anything about!”

Scholarship gap and bad actors

Performances of Lusitano’s music were uncommon until recent years, and those prior to 2020 did not program a representative sample.

The aforementioned chromatic motet “Heu me domine” was, essentially, the only piece of Lusitano’s heard in concerts, most likely because a modern transcription of the work became available in the 1970s. “Heu me domine” is presented in Lusitano’s manuscript treatise, Tratado de canto de organo, as an etude demonstrating the challenges of performing multi-part polyphony that uses the chromatic genus. This harkens back to the subject of Lusitano and Vicentino’s dispute.

Tratado de canto de organo was known as an anonymous work until the 1960s, when Robert Stevenson identified Lusitano as the author, citing shared musical examples between the manuscript and Lusitano’s Introduttione facilissima as well as unusual Spanish spelling that indicate the author primarily spoke Portuguese.

Several key precursors led to the current boom. Around 2010, Samuel J. Brannon, researching Lusitano for his dissertation at the University of North Carolina, stumbled on the Liber primus epigramatum, which had just been digitized by the Bavarian State Library.

Brannon produced his own modern editions of Lusitano’s motets, and by 2020 was excited to see the new surge of enthusiasm for the composer. But he was also concerned about bad actors: “People were latching on to the trend and attempting to make a buck by publishing hastily made transcriptions online.” To counter this, he re-edited his transcriptions and posted them to free online sites IMSLP and CPDL.

Liza Calisesi Maidens, choral director at the University of Illinois-Chicago, had been researching lesser-known Renaissance and Baroque choral works suitable for treble choirs, church choirs, and K-12 choirs. In the spring of 2020, Maidens and her research partner, Katy Maguire Lushman, learned about Lusitano’s madrigal “All’hor ch’ignuda.”

“The madrigal was of particular interest because it was written for only three voices. It was important for us to share flexible and accessible repertoire for choirs of varying degrees of ability, sizes, and voicings,” Calesisi Maidens explains. Finding copies of the original partbooks was difficult and not only because they were working at the height of a pandemic. She describes it as “a treasure hunt,” and after months of searching, they found all three partbooks in a library in Poland.

A composer’s renaissance

From Chanticleer’s December 2020 video of the motet “Ave spes nostra” to the Dessoff Choirs’ Lusitano performances at the end of 2022, the many groups who have programmed Lusitano’s music in the last two-and-a-half years have approached it with both respect and creative flexibility.

Andrus Madsen adapted his personal edition of the five-voice motet “Aspice Domine” for a group called X-tet, Boston Baroque’s resident chamber string ensemble. They recorded the piece for a concert documentary released in 2021, now available on YouTube. Taking “a really slow tempo with almost no vibrato, so they sound like viols,” Madsen explains, “is so stark, and beautiful and haunting.”

In the summer of 2021, Mark Cudek, artistic director of the Indianapolis Early Music Festival, added two of Lusitano’s motets to a program called Marginalia featuring soprano Esteli Gomez, a viol consort, and other instruments. The personnel forced Cudek to adapt these pieces from their more traditional format of a cappella voices. “We did ‘Heu me domine’ with just four viols and the ‘Regina coeli’ with Esteli singing the top line and the viols accompanying her.” Cudek was thrilled with the results: “That instrumentation worked beautifully, especially with viols which sustain so nicely.”

In September 2022, the Marian Consort released a CD, Vicente Lusitano: Motets, on the Linn Records label, which is the first commercial recording to exclusively feature motets from the Liber primus epigramatum collection. (In January, Karen M. Cook reviewed this album for the Early Music America website.) And the first quarter of 2023 has featured more exciting performances of Lusitano’s music, including a New York concert called Music of Portugal’s Golden Age in March.

One theme that emerges from these recent engagements with Lusitano is that his music is compelling, satisfying to perform, and unquestionably worthy of concert programs. Malcolm J. Merriweather joined Scottish-Congolese conductor Joseph McHardy and Chineke! Voices last summer for their London-area tour and recording project featuring several motets from Liber primus. Merriweather adores Lusitano’s interesting use of polyphonic textures, especially “the frequent duets between voice parts. I felt like sometimes there was a chamber music piece within the motet with three parts, but every part is singing around it.”

McHardy may be the only conductor who has performed both Lusitano’s Catholic motets and the Protestant work, “Beati Omnes,” giving him a broad perspective on the composer’s style. “In the Liber primus, clarity of text is less important than sound itself,” McHardy says. “Lusitano writes in an opulent, richly detailed style which can reach the realms of the ecstatic. It seems clear that his soundworld is very much generated by the shapes of the individual vocal lines themselves.”

On the other hand, McHardy notes, “‘Beati Omnes’ is punchy, direct, jovial. Each new note carries a new syllable and one can hear how the reforming emphasis on the intelligibility of the word is being realized in the music.” Overall, McHardy, whose Lusitano album with Chineke! Voices is scheduled to be released later this year, finds all of Lusitano’s works wonderful to perform. “To sing this music is almost an exercise in the pleasure of singing,” he says.

Thanks to reliable editions of Lusitano’s compositions available online, and a growing archive of YouTube performances, American early-music practitioners finally have the resources to revive Vicente Lusitano’s compositional voice.

Garrett Schumann is a composer and music scholar who teaches at the University of Michigan. His research and writings on Vicente Lusitano have been published by Grove Music, the New York Times, and VAN Magazine.