A Cross-Generational Community Learns to Love the Viol

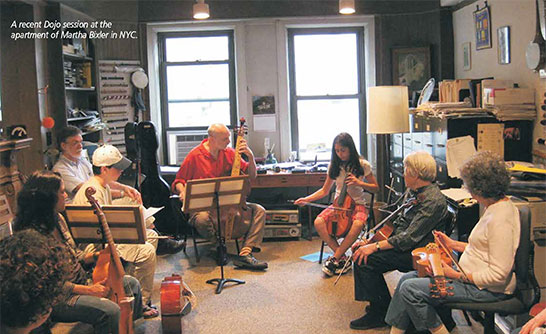

Where did you first run across early music? Did you take viol or recorder lessons at a community music school from someone like Grace Feld – man, who has taught for more than a half century at New Haven’s Neighbor – hood Music School? Did your music camp have an early instrument program, like the one that Mark Cudek has directed at Interlochen National Music Camp for four decades? Or did you wander into a collegium rehearsal at college as I did 45 years ago at Oberlin, when I dropped into Dean Nuern – berger’s office to retrieve a book and left with a tenor viol? In Manhattan, it could happen some Saturday morning if you were to knock on the door of Martha Bixler’s Upper West Side apartment, to find more than a dozen viol players of all ages and abilities participating in John Mark Rozendaal’s Viola da Gamba Dojo.

A viol player and Baroque cellist, Rozendaal started the Viola da Gamba Dojo in 2001 as a class at the Music Institute of Chicago in Evanston, Illinois. When he moved to New York in 2004, he brought it with him. He and his enthusiastic students were interviewed at the bi-annual Dojo Play-In held in June.

First of all, why group classes?

JMR: Music students do best when given the chance to meet each other and to have the pleasure and edification of ensemble playing. Choirs, orchestras, and bands provide that for singers and modern instrument players but no such institutions exist to bring the viol tribe together. The Dojo was created to provide all of that.

In the introduction to his Level 1 repertoire book, Rozendaal writes, “The Repertoire of the Dojo is designed to support and inspire the work of a community of learners dedicated to sharing the work, play, and growth that we experience with our beloved viola da gamba.” Indeed, the group learning aspect of the Dojo is one of the primary benefits of the experience.

Dawn Cieplensky: As a member of the Dojo, I am part of a loving community that has had longevity and continuity, growth, and development. For me it is a matrix of learning that I would not otherwise have—under John Mark’s direction and teaching, where players of all levels come together and play a repertoire that is ours.

What was your model for it?

JMR: Actually, I had four. When I started the Dojo, I was teaching group lessons for young cellists in the great Suzuki program at the Music Institute of Chicago, observing my son’s karate classes, singing in the Choir of Men and Boys at the Episcopal Church of Saint Luke in Evanston, and I was taking ballet classes myself—four different approaches to teaching performance skills.

In the Suzuki method, students worked in group and private lessons using a standardized repertoire. The common repertoire was carefully graduated to build skill upon skill in a doable progression—a great vehicle for sharing and reinforcing experience and motivation.

Similarly, in the karate dojo, students memorized and practiced a standard repertoire of “choreographies”— sequences of moves called “katas.” Students earned those famous colored belts in examinations for a given level, analogous to the series of books that contain the Suzuki repertoire. But, unlike most Suzuki classes here in the U.S., the karate dojo was a multi-level group; advanced students worked beside intermediate and very new students. This gave neophytes a model for every step of the path, and it offered more practiced students opportunities for leadership and teaching, both excellent ways of learning.

In the choir, I found an inspiring multi- level and inter-generational group— adults and children worked together with mutual respect and shared commitment.

At ballet class, I was intrigued by the structure of the class period. Every class at every level begins with pliés and simple knee bends at the barre and progresses through a careful varied sequence of simple, compound, and complex tasks until the end, when dancers have the chance to execute a few thrilling riffs across the length of the room. Years of study are telescoped, reviewed, and previewed in an hour; virtuosi do their pliés beside the neophytes. It makes one humble. (In ballet class I also re-learned the feeling of being really bad at something.)

Martha Bixler was one of John Mark’s first students when he moved to New York. She has the luxury of taking class in her own apartment, which she loves.

Martha Bixler: I got involved about ten years ago. John Mark came to New York City, and he had no place for the Dojo. So we decided to have it in my living room, and we’ve basically been doing it there ever since. He’s the only person who teaches all levels in one class, which is marvelous for me; he keeps going back to the basics. It’s not at all boring for the people who play well. It’s exciting.

Can you describe a typical class?

JMR: The Dojo sets up in a circle, with treble players on my left, tenors in the center, basses to the right. Music stands at first are placed behind the chairs. After we take a bow (borrowed from Suzuki classes, martial arts dojos, and zendos), we practice very simple exercises such as open string bow strokes and scales, watching each other so we can concentrate on making blended sounds and gestures. Then we replace our music stands to work from the Dojo repertoire, starting with simple songs and progressing to more difficult pieces. I choose repertoire based upon recent topics, future performances, and current participants (it is a drop-in class, a slightly different crowd each week).

Next, we practice music from outside the Dojo repertoire. For example, last year we included more 19th- and 20thcentury pieces so we could perform the “History of Western Music” at our spring Play-In. We have also performed the four-voice mass of William Byrd, Terry Riley’s In C, and excerpts from Taverner’s Missa “Gloria tibi Trinitas.” The end of the class often includes solo performances by students who have something prepared to share. And class always concludes with a bow.