by Loren Ludwig

Published May 2, 2022

This article was first published in the May 2020 issue of EMAg.

The James River Music Book contains the only known extant works for viola da gamba in British Colonial America.

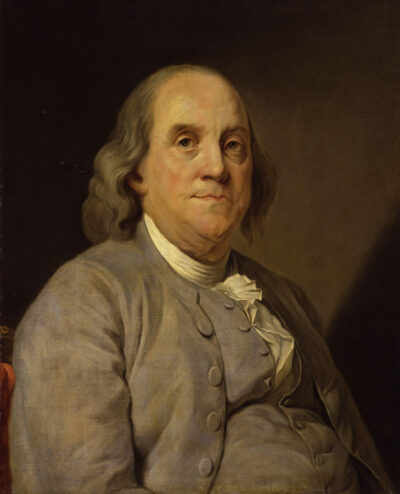

In 1789, Benjamin Franklin wrote to his agent in London from Philadelphia, “[Please] procure for me one of those little Books that teach to tune and play upon the Instrument called Viol de Gambo: which is about the Size of a Bass Viol, but is not the same, this having Six Strings. Send with the Book a Bow proper for the Instrument, and a Set of Strings.”

This was not the first mention of the viola da gamba in Franklin’s correspondence. About a decade earlier, his son had written him in France from embattled Philadelphia to report that the British had ransacked Franklin’s house and had “stole and carried off with them some of your musical Instruments, viz: a welch harp, bell harp, the set of tuned bells which were in a box, [and the] Viol de Gambo.”

By the final decades of the 18th century, the viola da gamba would have been an antiquarian curiosity—were it recognized at all—to the pillaging British soldiers or to the London shop where Franklin hoped his agent would find “the Instrument called Viol de Gambo.”

It is not known how or when Franklin became interested in the viol or where he acquired the instrument looted by the British from his house in Philadelphia. Musical-instrument making in Colonial North America was still in its infancy in the mid-18th century, and musicians relied on merchants to import instruments, strings, staff paper, sheet music, and other supplies from England or the continent. The few professional musicians active in the colonies during the 18th century would typically have been trained in Europe and brought their instruments with them. On the other hand, aristocratic amateurs—like Franklin—who modeled themselves on their British counterparts and maintained strong ties to Europe relied on agents to purchase and ship instruments and music from English and continental dealers.

But what of the viola da gamba? As musicologist Barbara Lambert documented, viols appear with some frequency in records of 17th-century Boston, though neither instruments nor music survive. Such records from Virginia and Maryland are much sparser. A Virginia court document from 1624, for example, records a libel suit alleging that one John Utie was insultingly referred to as a “fiddler” because he had been seen to “play vppon A violl [while] at sea.” The surviving 1685 estate inventory of another Virginian, Thomas Jordan, lists “a base viall unfixt.” An inventory from 1743 of the belongings of one Henry Carter of Lancaster County, VA, includes “a viol,” though 18th-century references to “viols” require caution: By the late 17th century, the term “viol” was as commonly used to refer to the violoncello as to the viola da gamba, a vagary of language that has complicated research on the instrument’s use in the 18th century.

These tidbits, while compelling, have proven insufficient to generate musical programs or reconstruct local performance practices. North American players and enthusiasts have had to rely entirely on their imaginations to connect their passion for the instrument with their region of residence.

But recent archival discoveries in Virginia and Maryland completely change this situation. In what follows, I will describe the James River Music Book (JRMB), a manuscript that has resided in Virginia since the 1730s and contains 15 works for solo viola da gamba, among other musical items. In addition, the earliest layer of the JRMB holds music by Lully, Purcell, and Handel, nearly doubling the page count of surviving instrumental music from the period and contributing repertoire for viola da gamba, organ, harpsichord, violin, and voice to the music now known to have been played in colonial Virginia.

While the British colonies to the north were settled by Christian fundamentalists fleeing religious persecution in Europe, the southern colonies of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Maryland attracted wealthy British speculators eager to cultivate the cash crop tobacco. Over the course of the 17th century, demand for tobacco in Europe increased tenfold. By the middle of the 18th century, there were nearly 150,000 enslaved people working the tobacco plantations of a wealthy planter class that saw itself as belonging to the English aristocracy on the other side of the Atlantic. And like their countrymen back in the Kingdom of Great Britain, the planters of Charleston, Williamsburg, and Annapolis cultivated as rich a musical life as they could.

By the early decades of the 18th century, records show that there were all sorts of European instruments—including strings (both bowed and plucked), winds, and the full range of keyboard instruments popular in Europe—in these so-called “tobacco colonies.” There were frequent opportunities to gather to play music, to hear concerts, and to dance, both in public gatherings and in aristocratic drawing rooms. As in Great Britain, amateur music clubs in the British colonies gathered to slash and burn their way through chamber music and to hire professional musicians to teach and perform for them.

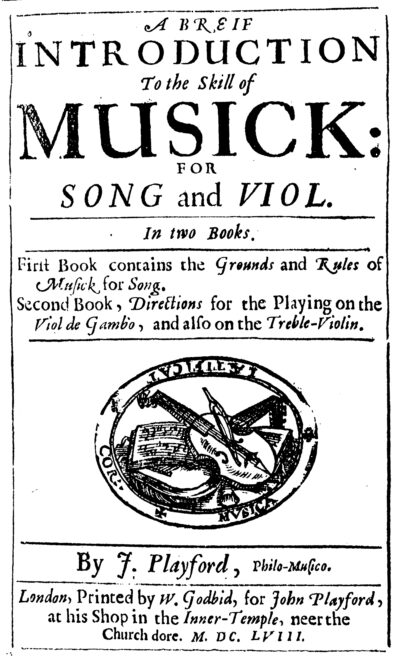

Inventories of the libraries of settler colonists—often compiled as part of their larger estate inventories—as well as surviving advertisements by book dealers and other merchants, offer a glimpse of some of the repertoire these colonial musicians likely played. While a few of these inventories have been studied by music scholars, such as Thomas Jefferson’s famous music library at Monticello, I found that numerous important items related to the viola da gamba had been overlooked “in the weeds” of scattered and incomplete colonial records. Among the publications that include music and instruction for the viol listed in colonial book collections are John Playford’s A brief introduction to the skill of musick (published in London in numerous editions from 1654-1730), which contains “directions for the playing on the viol de gambo,” and six “short lessons to the bass-viol” comprising five solo pieces and one duet (an almaine by Alphonso Ferrabosco [II]).

Inventories of the libraries of settler colonists—often compiled as part of their larger estate inventories—as well as surviving advertisements by book dealers and other merchants, offer a glimpse of some of the repertoire these colonial musicians likely played. While a few of these inventories have been studied by music scholars, such as Thomas Jefferson’s famous music library at Monticello, I found that numerous important items related to the viola da gamba had been overlooked “in the weeds” of scattered and incomplete colonial records. Among the publications that include music and instruction for the viol listed in colonial book collections are John Playford’s A brief introduction to the skill of musick (published in London in numerous editions from 1654-1730), which contains “directions for the playing on the viol de gambo,” and six “short lessons to the bass-viol” comprising five solo pieces and one duet (an almaine by Alphonso Ferrabosco [II]).

There were at least two copies of A brief instruction in Colonial Virginia, both of which appear in records from just after the turn of the 18th century. The current whereabouts of these volumes—if they survived the wars and other ravages of history—are unknown. (The several copies of Playford’s A brief instruction currently held by the Library of Virginia were acquired in the 1960s.)

Another item that offers specific musical works that we (now) know resided in the colonies is Christopher Simpson’s A compendium of practical musick, the 1667 and 1678 editions of which include instruction on the viol and a veritable library of chamber music for the viol in combination with other instruments. Simpson’s compendium includes, for example, six duets for “two bass viols,” six works for viola da gamba in tablature, eight “lessons for the treble, bass viol, and harp,” and numerous other pieces that do not specify any particular instrument but were presumably imagined as viol pieces by the printer.

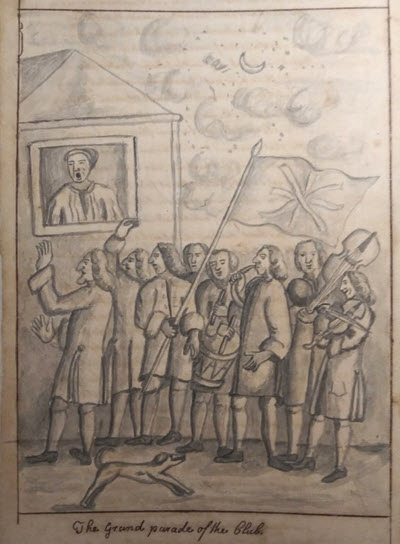

Simpson’s compendium is mentioned in a 1746 letter from the Annapolis viol player and Episcopal clergyman Thomas Bacon (1711-1768) to his friend Henry Callister, another Maryland music enthusiast: “I sent you Si—pson’s Compendium, which you will find easy & at the same time full enough for any young student in composition.” Bacon and Callister were members of the Tuesday Club of Annapolis, a group of wealthy and prominent colonists who gathered to play music and create elaborate Club rituals during the middle decades of the 18th century.

The Tuesday Club secretaries recorded thousands of pages documenting Club activities and transcribing some of the poetry, music, and proclamations of Club members, who were each referred to by humorous pseudonyms (Benjamin Franklin, for example, was Electro Vitrifico). Bacon, who emigrated from Ireland in the 1740s and seems to have served as the Club’s resident composer and leader of its ragtag band, is referred to as Signior Lardini. The records of the Tuesday Club mention that on May 26, 1747, Bacon performed on a “viol a gamba, or six stringed Bass.” Among other fascinating mentions of the instrument in Club papers is a poem recited at an event in 1754 that lists the banjo and viol in nearby lines—surely a uniquely “American” phenomenon.

“Sackbuts, Cymbals, Timbrels, lutes

Bangeos, dulcimers and flutes.

Bagpipe drones with Snuffling bellows,

Viols, violins, violoncellos

Pipes and Tabors, kettle drums,

Trumpets Shrill, and deep humstrums…”

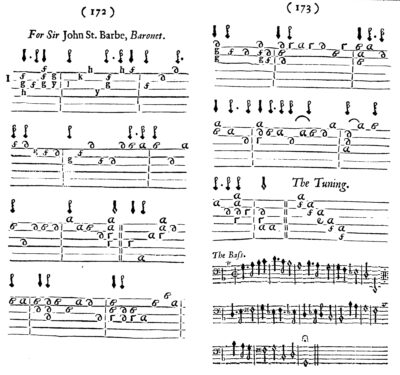

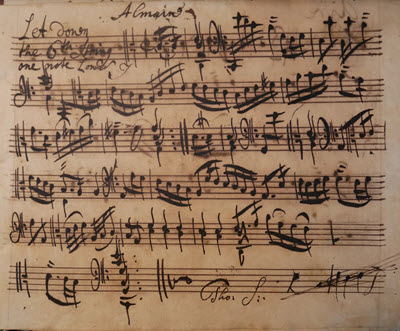

This brings us to the most compelling testament to the use of the viola da gamba in the British colonies, a manuscript containing more than a dozen solo works for viol known to have resided in Virginia since the 1730s. In the cases of the Playford and Simpson prints described above, only records of their presence survive, as opposed to actual copies from the 18th-century colonies. But the JRMB is an actual surviving manuscript that was owned and played from by musicians in Virginia and that contributes a dozen unica for viol—pieces that are otherwise entirely unknown. How do we know these works are for viola da gamba? Besides familiar notational markers, such as the use of bass and alto clefs and idiomatic chord spellings and ornament signs, the scribe removed all doubt by specifying that the reader “let down the 6th string one note lower.” Such an instruction could only be applied to an instrument with at least six strings (eliminating violin-family instruments), and the “dropped C” tuning that results from the instruction is familiar from English sources for viol of the period.

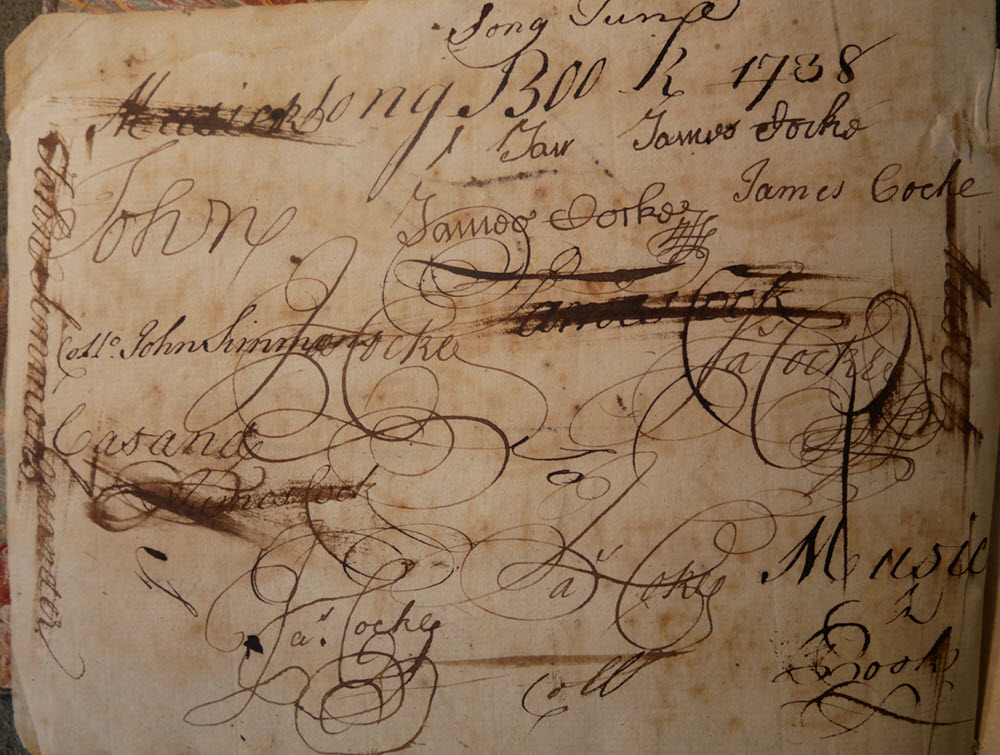

Listed in the catalogue of the Virginia Museum as “Musick song book, 1738,” the JRMB is a compilation of 34 leaves measuring approximately 6 x 7 3/4 inches. The earliest date to appear, on the verso of the second leaf, is 1738, in the same hand that signed the verso of the first leaf “Edward Tarpley His Book” in large, elegant cursive. While several later hands entered dozens of tunes and dances from the second half of the 18th and early 19th centuries, the earliest layer—which includes 15 dances and airs for viola da gamba, two pages of pedagogical material, a fragment of an aria from Handel’s opera Teseo arranged for keyboard, and three short “fugues for the organ”—appears to be in the hand of an experienced music copyist. The JRMB holds the only known extant works for viola da gamba in British Colonial America and appears to represent the earliest known appearance in the Colonies of instrumental music by Purcell, Lully, and Handel, as well as the earliest known source of music for organ. A James River Minuet later in the book provided my nickname for the collection.

The opening pages of the manuscript are covered with different signatures and pen tests entered by generations of subsequent owners of the manuscript (including one James Cocke, who would serve as Williamsburg’s mayor later in the 18th century). The quality of the music and the professionalism of the copying suggest that the earliest layer may have been complete before the manuscript was brought to Virginia. Certainly, the paper (bearing an Arms of Amsterdam watermark) and the music itself are of European origin. But who was Edward Tarpley, the earliest recorded owner? And what might have the circumstances been of the arrival and use of this mysterious collection in 18th-century Virginia?

Archival records show that Edward Ripping Tarpley was born to wealthy Virginia landowners in Richmond County, in 1727, and died in his 30s in Williamsburg in 1763. No surviving will of any members of the Tarpley family mentions a viola da gamba or other musical instrument, although most of the records relating to the Tarpley family were destroyed by fires in 1787 and 1865, including Edward’s estate inventory (if it existed). The Tarpley family owned a store in Colonial Williamsburg and socialized with the upper echelons of Virginia settler society, with whom they likely played chamber music and danced (social dancing was extremely popular in the 18th-century British colonies). Edward would have been about 12 when he signed the JRMB, and the manuscript passed to another member of the family upon his untimely death. While we can’t know with certainty whether Edward played the music in the earliest layer of the JRMB, we now know that this valuable collection of still nearly fashionable music resided in Coastal Virginia.

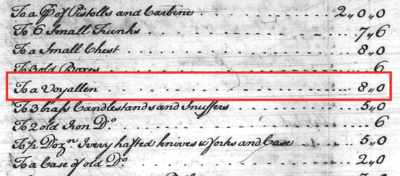

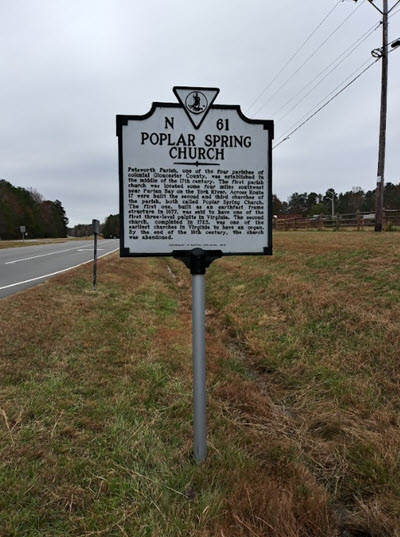

Another figure of potential importance to the story of the JRMB is the organist Anthony Collins, whose name appears in the Vestry Book of Petsworth Parish, Gloucester County, VA. Gloucester is located about 13 miles from Williamsburg—half a day’s ride plus a ferry crossing of the York River. During the late 1730s, the vestry committee commissioned an organ from England for the Poplar Springs Church. In June 1737, Collins was secured to assume the post of organist, which he held until 1740. He died in January 1741 in neighboring Middlesex County. His estate inventory records “a voyallen” and “a parcel of Musick Books.”

Collins’ musical expertise and the absence of records of him in Virginia prior to his marriage in 1732 suggest that he emigrated to the Colonies from England or Ireland, a possibility supported by the conspicuous absence of slaves listed in his estate. It seems likely that Collins was Tarpley’s music teacher and the possible origin of the music in the earliest layer of the JRMB.

The Poplar Springs Church—and its organ, one of the first in colonial Virginia—was destroyed in the early 19th century, though the Parson’s house still stands near the historical marker dedicated to the long-overgrown location of the church. The house dates to the middle of the 18th century, and when I knocked on the door on a recent research trip, I was welcomed inside by the friendly, historically minded owners. I had recently performed the solo music from the JRMB in a program at Colonial Williamsburg, and I asked whether I might play a few of those pieces in one of the original surviving rooms of the house. I like to imagine that those walls—which may have heard impromptu performances by Collins and members of the vestry committee following services at the nearby church—recognized the music that had likely traveled with Collins from Europe and made its way from Gloucester to Williamsburg and the possession of the young Edward Tarpley.

The petite, binary dances in the opening pages of the JRMB closely resemble solo works for viol that appeared around the turn of the 18th century in England (think Benjamin Hely’s c.1700 The complete violist or the later editions of Playford’s Musicks recreation on the viol, lyra-way). By the last decades of the 17th century, English composers had completely digested the French dance idiom for solo viol of the previous generations. That English viol players adopted French style in unaccompanied music from the early 18th century complicated my search for concordances, because it meant that any source containing English or French solo music from the period became a candidate. It also suggests that the French-style pieces in the JRMB represent a holdout of French music in the Colonies, which would become increasingly Italophilic as the 18th century progressed; Jefferson’s famous preference for Italian music is just one example.

The petite, binary dances in the opening pages of the JRMB closely resemble solo works for viol that appeared around the turn of the 18th century in England (think Benjamin Hely’s c.1700 The complete violist or the later editions of Playford’s Musicks recreation on the viol, lyra-way). By the last decades of the 17th century, English composers had completely digested the French dance idiom for solo viol of the previous generations. That English viol players adopted French style in unaccompanied music from the early 18th century complicated my search for concordances, because it meant that any source containing English or French solo music from the period became a candidate. It also suggests that the French-style pieces in the JRMB represent a holdout of French music in the Colonies, which would become increasingly Italophilic as the 18th century progressed; Jefferson’s famous preference for Italian music is just one example.

As the JRMB becomes better known (my scholarly article on the source is under review and my recording of the suites—generously supported by the Viola da Gamba Society of America—will be out later in 2020), more of its contents may be positively identified. This may help fill in some of the missing story of the manuscript’s likely trip from Europe to the Virginia Colony during the 1730s, as well as, perhaps, the generations of musicians who played from the manuscript and later copied into it fiddle and dance tunes. As in the case of the Tuesday Club poem above, in which “bangoes” and “viols” live side by side, the JRMB features antique dances for viola da gamba alongside Virginia tunes like “Butter’d peas” and “The James River Minuet.” This mixture is, of course, uniquely American, and suggests a story of adaptation and syncretism—including the centrality of slavery and the presence of enslaved peoples and their cultures—that continues to transform how we imagine the music of the period.

Loren Ludwig is a scholar/performer based in Baltimore. He researches what he describes as “polyphonic intimacy,” the idea that music in the Western tradition is constructed to foster social relationships among its performers and listeners. Ludwig is a co-founder of LeStrange Viols and Science Ficta and performs with ACRONYM and numerous ensembles in the U.S. and abroad. He also serves as program coordinator for the program in the Arts, Humanities, & Health at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.