by Wendy Heller

Published January 15, 2024

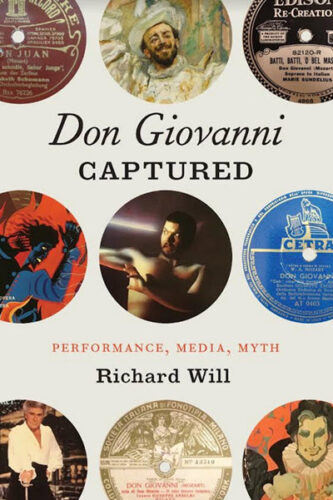

Don Giovanni Captured: Performance, Media, Myth by Richard Will. University of Chicago Press, 2022. 301 pages.

Don Giovanni is perhaps Mozart’s most alluring and controversial opera. Enthusiastically received at its 1787 premiere in Prague, Mozart and librettist Lorenzo da Ponte’s operatic portrayal of the libertine seducer Don Juan has inspired a wide range of reactions among scholars, critics, and audiences. The Romantics of the 19th century were particularly taken by the dark grandeur of Mozart’s music, the supernatural elements (especially the chilling moment when Don Giovanni descends to hell), and were fascinated by the Don’s libertine tendencies and sexual prowess.

For example, in 1813 the writer, composer, and music critic E.T.A. Hoffmann (best known today for writing the stories that inspired Offenbach’s Tales of Hoffmann) even published an influential short story about the opera in the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitschrift. In his “Don Juan,” a young man, whose hotel room, which magically leads directly into a private box in the theater, attends a performance of Don Giovanni. Utterly bewitched by the seething sensuality of Donna Anna, Hoffmann’s unnamed hero imagines her to be entirely overcome by the passion and pleasure triggered by the Don’s assault.

Some 20th-century commentators, inspired by Freud and psychoanalytical theory, would ponder Donna Anna’s Oedipal tendencies, while producers and audiences influenced by Hollywood readily pictured Don as the hero of a swashbuckling costume drama. By the 1990s, critics, directors, and operagoers became increasingly concerned about the underlying sexual violence. Director Peter Sellars summed up the situation succinctly when he quipped: “There’s a rape and murder in the first ninety seconds of Mozart’s Don Giovanni,” adding that it is “probably the greatest opera ever written…[that] 200 years later, we’re still struggling to understand.”

Richard Will’s engaging new book, Don Giovanni Captured: Performance, Media, Myth, takes on this struggle, albeit not through a conventional musicological analysis of the opera. Instead, he provides us with a comprehensive examination of the vast treasure trove of recordings of Don Giovanni from the early 1900s to the present that show the variety of ways in which the opera has been interpreted by generations of singers, conductors, directors, and record companies. (The appendix includes a valuable discography).

The first part of the book focuses on the many early 20th-century recordings that included only excerpts from the opera, most notably those made at 78 rpm which could hold barely five minutes of music, as opposed to the 20 minutes on each side of a 33 1/3 LP and the 75-80 minutes on a CD. (The author reminds us that the first complete recording of Don Giovanni, released in 1936 on 78s, required 23 double-sided discs!) The second section considers complete recordings of the opera on LP and CD, while the final section concentrates on video recordings, which play such an important role on YouTube and in the music history classroom today.

This insightful and original study illuminates fundamental trends in the performance of Mozart over the past 125 years, while also exploring the history of the recording industry as well as demonstrating the implications of performance choices for understanding the opera’s many complexities. Considering some 20 recordings of Don Giovanni’s Act II, scene 1 serenade “Deh, vieni alla finestra,” for instance, the author compares representative performances by Victor Maurel (1904) and Ezio Pinza (1930). Maurel, like many of his colleagues born before the turn of the century, sang Mozart with far more freedom and spontaneity than we are accustomed to today; his rhythmic flexibility, frequent changes of dynamics, and use of ornaments capture the intensity of the Don’s passion. Pinza and the baritones of his generation focused more on “articulating phrases and forms, in tempo and without decoration.” Pinza’s Don Giovanni sings with what the author describes as a kind of “modernist urbanity — a cool customer, with the suavity of an experienced sexual predator.” The book’s dedicated website (https://press.uchicago.edu/sites/will/index.html) includes a host of supplementary audio and visual examples that allows the reader listen to these examples and judge for themselves.

Further insights emerge from Will’s consideration of the complete recordings of the opera. While recitatives rarely garner much discussion, Richard Will shows how singers in the second half of the 20th century have tended to perform Mozart’s recitatives more slowly and make them more expressive. The style of accompaniment has changed, too: the uncredited harpsichordist for Ferenc Fricsay’s 1958 recording on Deutsche Grammophon uses rolled chords only for climactic moments, with simple block chords as the norm. John Constable on Colin Davis’ recording from 1973 is one of several harpsichordists who, using a livelier style and changes in texture and registration, adds a far more robust vocabulary of sonic effects.

Attitudes about tempos — particularly in dance-inspired movements — have also changed. The author provides an especially insightful discussion of tempo in the Act I finale, when the tension created by the simultaneous performance of three different dances (minuet, contradanse, and “Deutscher” or fast waltz) in three different meters (3/4, 2/4, 3/8) culminates in Zerlina’s climactic off-stage scream in response to Giovanni’s attack. The author describes how the faster minuet tempo used in most performances from the 1990s creates a more “urgent and chaotic” feeling that underscores Don Giovanni’s threat, whereas a more placid minuet “seems to trap all the characters except Don Giovanni in a kind of spell.”

Will’s analyses of the video recordings in the final section of the book encourage us to think not only about a given production’s visual elements — the setting, costumes, staging, and acting style — but also the strategies used by videographers to control the viewer’s gaze. In the first scene, for instance, the camera might focus on Leporello impatiently waiting for his master to finish his business, then move upward to zoom in on Donna Anna’s struggle with Don Giovanni or cut away to give a view of the entire stage, these choices necessarily impacting the viewer’s impressions of the opera’s violent beginning.

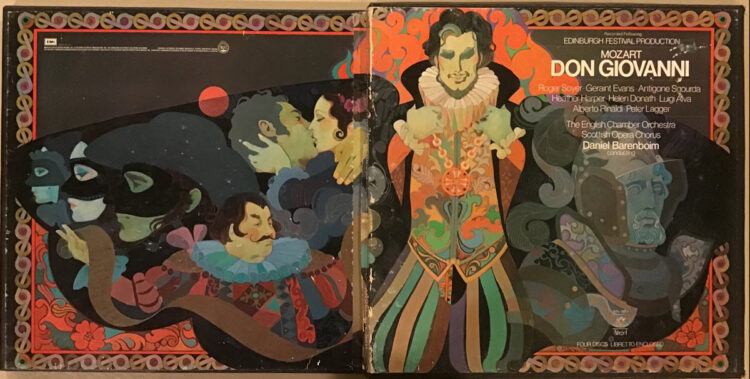

The author also provides valuable insights into the extensive extra materials that accompany the 78s, LPs, CDs, and video recordings. These can include translations and subtitles that emphasize or disguise sexual violence; the sense of the opera conveyed on album covers; and the essays that analyze the opera or make claims about a given performance’s historical authenticity, as René Jacobs did for his 2006 recording of Don Giovanni for Harmonia Mundi.

Don Giovanni Captured does not endorse any one version or interpretation of the opera. Instead, Will reminds us that every production has meaning, that performance traditions are unstable, temperamental, and as changeable as the weather, and that the best way to love Don Giovanni is to embrace the diversity and richness of the opera’s performance history. Sound recordings have much to teach us, if we but take the time to listen.

Wendy Heller is the Scheide Professor of Music History at Princeton University. Author of Music in the Baroque, Heller is currently completing a book entitled Animating Ovid: Opera and the Metamorphosis of Antiquity in Early Modern Italy. Her edition of Francesco Cavall’s Veremonda l’amazzone di Aragona will be published by Bärenreiter in 2024.