by Aaron Keebaugh

Published December 16, 2024

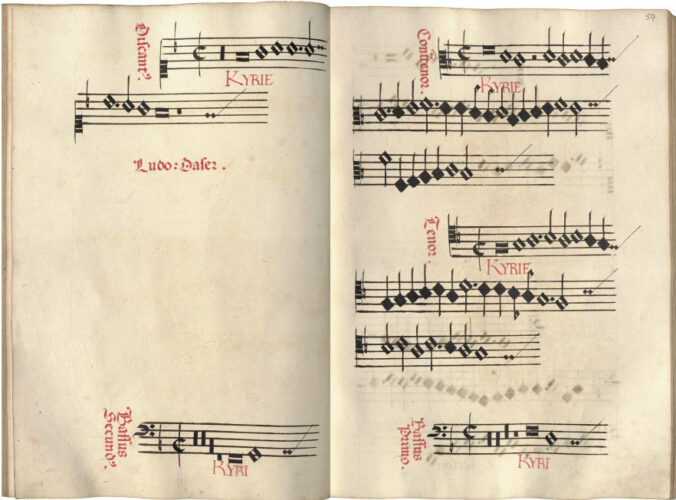

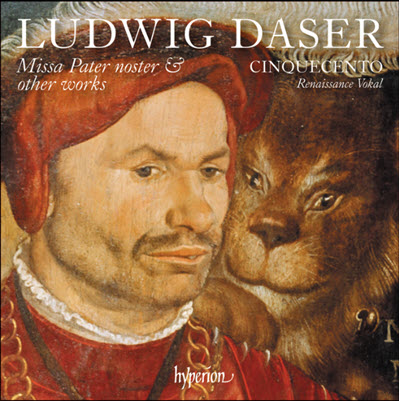

Ludwig Daser, Missa Pater noster. Cinquecento. Hyperion CDA 68414

Listening to the music of Ludwig Daser is like peering through the mist to discover a forgotten legacy. Prominent between the careers of Ludwig Senfl and Orlande de Lassus at the Bavarian Hofkapelle, Daser (1526-1589) is typically considered a transitional figure. Yet he was just as cosmopolitan, absorbing the Netherlandish styles so prominent in the work of his predecessors Heinrich Isaac and Josquin des Prez.

Daser is chiefly remembered for being caught in the political headwinds of his time and place. Sympathetic to Martin Luther’s reforms, the composer fell afoul of the Catholic powers at the Bavarian court. He was dismissed from his post there in 1563, and much of his music has fallen by the wayside.

Fortunately, Cinquecento has shed welcome light on the work of this frequently overlooked figure. Smooth, resonant, and searchingly intimate, their performances of Daser’s Missa Pater noster and various motets reveal a compositional voice that fits squarely within the world in which the composer dwelt. But whether this music rises to a level worthy of international renown — even today — is another matter.

However fixed in his time, Daser still possessed a lyrical gift that earned him admiration. His motets, parody masses, and German hymns reflect trends of his immediate past. Like the work of Senfl and Isaac, Daser’s sacred music is episodic, moving freely between chant and polyphonic sections in ways that can feel a little jarring. The cadential sections emerge suddenly from sustained voices that the harmonies simply latch onto. The effect may by surprising, but it comes out of nowhere, eschewing any resolution. Satisfaction is fleeting.

Yet there are beautiful moments along the way. The Missa Pater noster, possibly Daser’s most enigmatic score, makes a spectacle of such textural richness. The lines of the Kyrie flow gingerly; the Christe resonates with dark inflection. The Cinquecento singers perform them with clarion assurance, the treble voices bringing momentary splashes of light.

Lines in the higher tessituras ride like foam along the gentle waves of the Gloria. One cadence produces yet another lapping phrase, and the singers let it drift by striking the right balance between horizontal arc and vertical rhythm. The Credo is just as haunting; the Sanctus and Agnus Dei, by contrast, are vibrant and stark. Though it ends sorrowfully, the singers reveal hints of touching sweetness.

Other works are more of a showcase for the Cinquecento ensemble. Daser’s Benedictus Dominus is a textural marvel where sturdy, oaken basses anchor the pure-toned treble voices. Dynamic swells enhance all the textural colors. They do the same in Salvum me fac, where the voices glow with distant warmth. The singers are resplendent in Fracta diuturnis, the lines weaving an elegant sonic tapestry. Yet tension remains palpable, as evidenced in the trumpeting assurances of the Fratres sobrii estote.

Daser stripped his style of such grandeur for his Protestant hymn settings. And the singers aptly convey the sudden earthiness. They bring a hearty, down-home feel to Danck sagen wir alle. Their lines lift as much as lilt in Daran gedenck Jabob und Israel. If Luther’s theology aimed to steer clear of worldly excess, the singers still suggest the sheer exuberance beneath the surface.

Yet Daser’s skill is letting the listener sit in the very moment. The Christe, qui lux es et dies moves between solitude and almost stultifying apprehension. Single lines flower suddenly into two voices before encompassing the full ensemble, seeking yet not quite finding a way out of the tension. But Cinquecento lets those moment ring starkly. As the final Amen suggests peace and serenity, there’s a sense that personal convictions will endure. In that, Daser’s life and work can be most instructive.

Musicologist Aaron Keebaugh’s work has appeared in The Musical Times, Corymbus, The Classical Review, The Boston Musical Intelligencer, and The Arts Fuse, for which he serves as regular Boston critic.