by

Published October 21, 2016

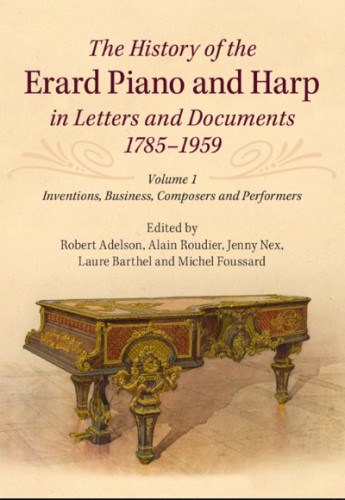

The History of the Erard Piano and Harp in Letters and Documents, 1785-1959.

Robert Adelson, Alain Roudier, Jenny Nex, Laure Barthel, and Michel Foussard, editors.

2 volumes, 1134 pages. Cambridge University Press, 2015.

By Nicholas Renouf

BOOK REVIEW — Drawn from the Gaveau-Érard-Pleyel Archives now maintained by the AXA Insurance Group in France, this sumptuously produced two-volume set about the history of the Érard piano and harp represents a rich lode of information not only for those interested in these instruments, but also for all who want to learn about the role of music within the context of European culture of the last two centuries.

It would be difficult to overestimate the inventive genius of Sébastien Érard (1752-1831). At the age of sixteen, Sébastien, who had apprenticed himself in his native Strasbourg to the keyboard maker Johann Heinrich Silbermann, left for Paris. While still in his twenties, Érard had already mastered the art of keyboard instrument making. Protected by a privilège du roi at the end of the reign of Louis XVI, he provided both harpsichords and pianofortes to members of the highest levels of society. His royalist associations obliged him to withdraw to London for a period during the Reign of Terror. There, he continued to improve the mechanism of the piano, as well as that of the harp. His success ultimately resulted in patents, both English and French, which revolutionized the manufacture of the two instruments and resulted in the development of the modern grand piano and concert harp.

It would be difficult to overestimate the inventive genius of Sébastien Érard (1752-1831). At the age of sixteen, Sébastien, who had apprenticed himself in his native Strasbourg to the keyboard maker Johann Heinrich Silbermann, left for Paris. While still in his twenties, Érard had already mastered the art of keyboard instrument making. Protected by a privilège du roi at the end of the reign of Louis XVI, he provided both harpsichords and pianofortes to members of the highest levels of society. His royalist associations obliged him to withdraw to London for a period during the Reign of Terror. There, he continued to improve the mechanism of the piano, as well as that of the harp. His success ultimately resulted in patents, both English and French, which revolutionized the manufacture of the two instruments and resulted in the development of the modern grand piano and concert harp.

Érard’s inventive successes gave rise to a business that became a nexus for the musical world of 19th-century bourgeois society. With the aid of older brother Jean-Baptiste and nephew Pierre, both instinctive businessmen, Maison Érard rapidly expanded operations in both Paris and London. The firm was especially successful in exploiting its relationships with many of the most important pianists and composers of the day. The symbiotic relationship between the Érard company and such musicians as Liszt, Thalberg, and Mendelssohn — and later Saint-Saëns, Fauré, Massenet, and Ravel — exemplifies an ongoing fruitful interaction of the forces of art, technology, and commerce. All of this is impressively documented in the letters, patents, testimonials, and other items assembled and painstakingly annotated in these books.

It has long been assumed that the repetition action was key to the flowering of the Romantic-era pianism of Liszt and Chopin. Pierre Érard’s letter to his uncle in Paris on June 22, 1824, describing the 13-year-old Liszt’s London debut brings to life this history-making premiere for artist and instrument:

Dear uncle,

Liszt’s concert yesterday was a real triumph for your piano! The room where he played is very big but very good for music. The whole piano world was there. Clementi, Cramer, Kalkbrenner, Ries. They were all surprised by the young Liszt, who truly played in the most amazing way, and much better than I had ever heard him. The entire audience and all the teachers agree that the piano is the best that has ever been heard in public!

Nearly a century later, during an era when German Bechsteins and American Steinways had already made significant inroads even in France, Fauré revealed his “brand loyalty” to the Érards with a jocular remark in a 1910 letter to Albert Blondel, director of Maison Érard from 1879 to 1935: “In any case, if ever anyone says that Érards are dry, send me the insolent one!”

When first confronted with these books, this reviewer had some reservations that the overwhelming extent of these archives might be better served by their presentation in a searchable, online digital archive. However, longer acquaintance with these tomes has led to a deep appreciation of the judicious selection, organization, and impeccable annotation of the documents and letters exercised here. The books allow the reader to look beyond the information on the subject presented in biographies and scholarly articles — interpreted and filtered by a secondary author — to arrive at a direct examination of the granular and contemporary factual evidence.

The five editors and those who aided them in publishing this monumental publication deserve the highest praise for an important work very well done. Researchers and amateur “pianomanes” who may wish to go even further should be encouraged by the footnote on page 2 of the introduction referencing the Centre Sébastien Érard, where we may hope an increasing number of primary source documents of the Gaveau-Érard-Pleyel archives will continue to be made available.

An alumnus of New England Conservatory and the Yale School of Music, Nicholas Renouf is curator at the Yale Collection of Musical Instruments, director of music at St. Mary’s Church in New Haven, and co-founder of the Saint Gregory Society.