by Jeffrey Baxter

Published July 8, 2024

AUFERSTEHUNG (RESURRECTION), a YouTube film inspired by Heinrich Schütz’s Auferstehungs-Historie. Ensemble Polyharmonique, led by Alexander Schneider, produced in collaboration with CentreFilms. (Audio CD available on Accentus music ACC30620)

For the 400th anniversary of Heinrich Schütz’s Easter oratorio Historia der Auferstehung Jesu Christi (SWV 50), in April 2023, Ensemble Polyharmonique released an audio CD of their performance. Shortly thereafter, the Dresden-based early-music group embarked on a visual representation of the work, collaborating with a local studio of professional filmmakers, CentreFilms. The 50-minute project, RESURRECTION, is billed as “a film-tale about love, faith, and the incomprehensible, with music by Heinrich Schütz.”

The collaborators were guided by a vision from Ensemble Polyharmonique’s artistic advisor and dramaturg, Dr. Oliver Geisler. Together, they describe their conception of the oratorio as “a quiet and concentrated work with a refined dramaturgy in which the Easter jubilation only slow breaks through” and call their project as “an entirely new approach to this Baroque masterwork: Today’s viewers are confronted with the ways they deal with doubt, hope, consolation, fear, and unbridled happiness.”

Ensemble Polyharmonique and CentreFilm’s complete film ‘RESURRECTION,’ inspired by Heinrich Schütz’s ‘Auferstehungs-Historie’

Before watching the film, I wanted both to refresh my memory of this historic music and to hear what interpretive choices were made, specifically those of potential doubling wind instruments, continuo configuration, and flexible vocal assignments — important performance-practice hints all outlined by the composer in great detail in his 1623 publication. With score in hand, I listened to Ensemble Polyharmonique’s recording and was thrilled to hear the artistry and depth of understanding that these performers bring to this contemplative and often over-looked piece. Their fine audio performance — including the bold group-improvised string accompaniment under the plainchant of the Evangelist, tenor Johannes Gaubitz; the color choices of Baroque bassoon and varied plucked continuo instruments; and trombones in key choruses — deserves high praise. Perhaps even in a separate review.

CentreFilms, the small German collective of advertising and image-film professionals, have a diverse portfolio that includes a hipster ad for Deutsche Bahn and a fast-flying drone ad for the Bachakademie Stuttgart. Their website describes their mindset: “We don’t just create target group content. We promise goosebumps.”

The AUFERSTEHUNG film, with many haunting and strangely beautiful scenes, is richly presented in slow-moving, often gripping images and doesn’t attempt to represent or propel any action, although their disparate parts appear rather as a series of unrelated expositions. By design, it’s about impressions and reactions, never adding up to a comprehensive experience.

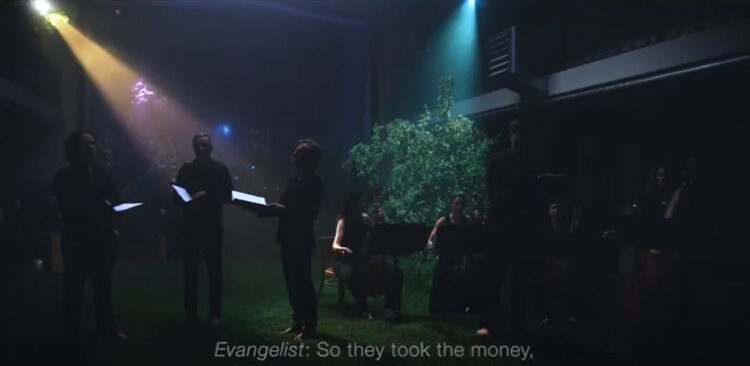

A small, seated audience is depicted quietly observing a “concert.” The performers are sometimes visible, wearing simple black and red concert attire and barefoot on green astro-turf. Images of the musicians are often overlaid with scenes of wide-open nature, extreme close-ups (a human eye as a window of the soul?), intervening and intruding interpretive dancers, and even vast expanses on the four elements: earth, air, fire, and water. There’s quite a bit of water imagery that’s either heavy on “tears” or a Freudian representation of the subconscious. (Schütz’s own written suggestion, in the detailed preface to his score, indicates that only the Evangelist should be seen, and not the choir.)

An opportunity provided by the ensemble’s musical director, Alexander Schneider, proves advantageous for the filmmakers: a brief, six-measure instrumental Sinfonia from Schütz’s 1666 Passion-motet, “O bone Jesu” (SWV 471), is interpolated at three points into the work’s eight inner scenes, thus framing the action and providing a ritornello for contemplative “breathing space.” It is in these moments that the film’s broad imagery may be most effective, unfolding without any sung text.

Two dancers are incorporated at various points in improvised (and unmetered) appearances: Giulia Russo, who evokes a Lucinda Childs-inspired manic style, and Christian Zacharas (aka “Robozee”), who describes his robotic moves as stemming from “the urban dance scene” where he performs “illusionary dance forms such as animation, waving, popping, and telling.”

The filmmakers make an interesting choice of imagery, one that reflect the composer’s unusual vocal disposition of the “roles” of Jesus and Mary Magdalene, since both individuals are musically represented by vocal duets. This duality, and the expressive power of two singers per character, are seen in the film’s differing visual suggestions of the two title characters, sometimes also acted by alto countertenor Schneider (the group’s director) and soprano Magdalene Harer, and sometimes suggested by the dance couple.

The interpolation of dancers comes off as a curious artistic move: their improvised movements — intentionally not choreographed with any rhythmic suggestions of the music — can sometimes suggest a sense of Mary’s distress, or a history of demon-possession, or of healing. But often times it’s distracting and confounding. The dancer Robozee’s silent popping and locking seems merely to remind the viewer of nothing deeper than “Oh, here is a disconnected image from contemporary life.” (To my tastes, a more effective incorporation of street dance in a Baroque work was seen in the memorable 2019 Paris Opera production of Rameau’s Les Indes Galantes.)

That said, the general tone and slow-moving pace of Ensemble Polyharmonique’s film captures the reflective nature of Schütz’s work, which — apart from the final chorus — eschews ebullient celebration for quiet meditation, inviting the listener to ponder the complexities of doubt and faith. With so much to consider, the filmmakers created a “behind the scenes” explanation video, too.

Jeffrey Baxter is a retired choral administrator of the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, where he managed and sang in its all-volunteer chorus and was an assistant to Robert Shaw. He holds a doctorate in choral music from The College-Conservatory of Music of the University of Cincinnati and has written for BACH – The Journal of the Riemenschneider Bach Institute, The Choral Journal, and ArtsATL. For Early Music America, he recently reviewed Cantata Collective’s B-minor Mass.