by Steven Silverman

Published March 30, 2025

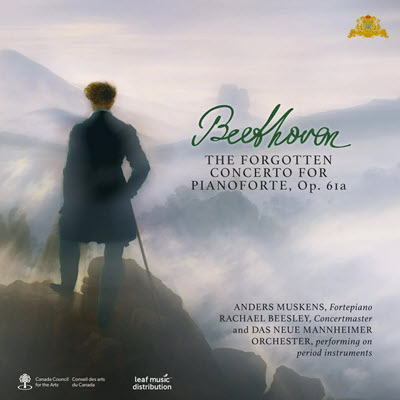

Beethoven: The Forgotten Concerto for Pianoforte, Op. 61a. Anders Muskens, fortepiano, and Rachael Beesley, concertmaster, with Das Neue Mannheimer Orchester. Leaf Music AM202401

Beethoven’s now-beloved Violin Concerto premiered in 1806 to a mixed reception and general confusion by the audience. A year later, Muzio Clementi — at the time not only a celebrated composer and performer, but also a music publisher and instrument builder — commissioned Beethoven to produce a fortepiano version of the concert. Leaving the orchestra parts untouched, Beethoven created the soloist transcription that same year, possibly with assistance from his students Czerny and Ries. He evidently considered it important enough to warrant its own opus number: Op. 61a. The new version preserves the violin part essentially intact, and so is mostly a right-hand piece, although there are some left-hand harmonic reinforcing (particularly in the final movement), octave doublings, Alberti bass accompaniments (especially in the slow movement), and the occasional obligato moment (including some insouciant additions to the theme of the Rondo).

What is brand new is an enormous cadenza for the first movement, written out by Beethoven. This is of great interest, since there is no comparable Beethoven cadenza for the original violin version. In fact, this new cadenza is the longest section of the opening movement, and contains not only plenty of requisite piano flourishes, but, of all things, a dialogue between piano and timpani — using the famous five-note drum beat that opens the concerto — plus a martial episode having nothing to do with the rest of the movement.

This keyboard version of the concerto is not quite as forgotten as the album title suggests. Peter Serkin, among many modern pianists, have played it; Some violinists (including Gidon Kremer) have adapted the first-movement cadenza for performance, and various recorded versions can be found online. Nonetheless, this is anything but a mainstream piece.

Fortepianist Anders Muskens and his period-instrument band give it a rousing go. Tempi are noticeably and convincingly flexible. Every movement starts off a bit more briskly than one usually hears, but there is plenty of pushing and pulling throughout which mostly fit the music, such as accelerating toward climactic moments like the end of the exposition and recapitulation in the opening movement. (One place I question, though, was a pronounced ritard at the Rondo’s final statement before the final chords; this ought to go tripping off into the sunset.)

There is also frequent use of string portamento — some discrete sliding into notes — that gives an unusual color that’s especially notable in the first movement’s lyric theme when it appears in the minor. The orchestra sounds robust in the tuttis (although the low strings are a little weak) and the period timpani,which figures so prominently in the opening movement is a delight: little exclamation points for beats instead of the portentous overlapping rumblings one unavoidably gets on the reverberant modern instrument. The liner notes tell us that timpanist Rubén Castillo del Pozo here plays original Schrauben-pauken, made around 1780 in Bavaria.

Muskens plays a restored 1806 Broadwood fortepiano. Much of the solo part lies in the topmost register, which has a distinct timbre (far less homogeneous than a modern Steinway) which suits the music’s seraphic character. The performance is absolutely technically up to snuff. Muskens’ trills are imaginatively rendered — expressive, played with varied speeds and with variety in passages where there are multiple successive trills. Passagework is likewise right there throughout. He coaxes nice dynamics from the instrument, with some of the tapered phrase endings in the slow movement working especially well. And he works up a fine frenzy in that big first movement cadenza.

Muskens plays much of the solo part non-legato — the slow movement excepted — and is discrete with the pedal, using it almost as an ornamental color. But there are a few exceptional spots where he pedals through measures at a time for a radically different sound, as in the passage just before the return of theme at the end of the first movement’s development section. His phrasing reflects the instrument’s quick decay, and so is more truncated than one hears in the violin version; on the fortepiano it can occasionally sound a little choppy if one doesn’t already know the piece.

Beethoven wrote not only the first-movement cadenza, but also a bridge cadenza between the second and third movements, and two cadenzas for the finale. Muskens instead plays his own in place of the composer’s. The most extended is in the final movement, before the coda. This nearly three-minute interpolation — which uses the horn-call part of the Rondo theme (as does Beethoven’s cadenza at the same spot) and then adds horn-call imitations from other 19th century composers — goes on too long for my taste. At this point, there is a lot of momentum in the music, and we can already see the finish. Run for that goal line!

So as Beethoven’s transcription throws some new light on his masterwork, this period-instrument rendition throws new light on the transcription itself. Recommended indeed.

Steven Silverman is a pianist and harpsichordist whose performances include concerts at Weill Hall in New York City and the Salle Cortot in Paris. He and his wife, the violinist and violist Nina Falk, are co-founders of the Arcovoce Chamber Ensemble, now in its 26th season. For Early Music America, he recently reviewed Mahan Esfahani’s latest Bach recording.