by Jeffrey Baxter

Published November 6, 2023

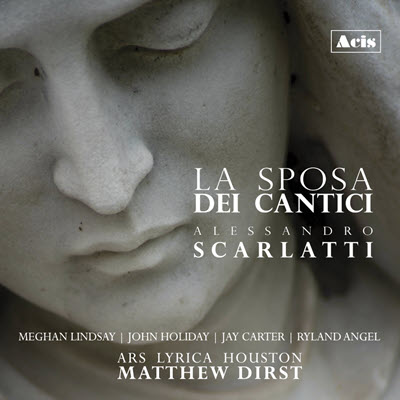

Alessandro Scarlatti: ‘La Sposa dei cantici’ Ars Lyrica Houston led by Matthew Dirst, with soprano Meghan Lindsay, and countertenors John Holiday, Jay Carter and Ryland Angel. Acis APL53721

Many contemporary singers are likely to only know Alessandro Scarlatti as creator of a handful of the most frequently heard 24 Italian Songs & Arias — a century-old “greatest hits” anthology that includes his “Già sole dal Gange,” “Le Violette,” and “O cessate di piagarmi.” For the weary ears of worn-out teachers and vocal judges — crying O cessate! themselves — Ars Lyrica Houston offers us a respite in this elegantly performed reminder of Scarlatti’s enormous talent.

The two Scarlattis, father and son, were prodigious talents of the Italian Baroque, from son Domenico’s 500 famously innovative keyboard sonatas to father Alessandro’s oeuvre of some 100 operas, 600 solo cantatas, and 30 oratorios. The oratorio repertoire is represented in this new Ars Lyrica Houston’s project, a world premiere recording of papa Scarlatti’s 1710 Naples-version of his 1703 oratorio.

As director Matthew Dirst writes, “at its 1703 première at the Oratorio dei Filippini di Sancti Cantici (St. Philip Neri) in Rome, the work was presented as a Cantata per l’Assunzione della Beata Vergine, which suggests performance on or around the Feast of the Assumption. Scarlatti and his librettist revised the work somewhat for a 1710 performance in Naples, where it was retitled La sposa dei cantici (“The Bride of Songs”).

Working from manuscripts preserved in the Stanford University Memorial Library of Music and the Bibliotheque National in Paris, Dirst and his team reconstructed this 90-minute work that features a quartet of soloists (in named roles) and an orchestra of strings and continuo, since wind instruments in sacred dramas were often banned by various popes around 1700.

The oratorio’s genesis owes something to Scarlatti’s lengthy collaboration with Cardinal Pietro Ottoboni (1667–1740), great-nephew to Pope Alexander VIII and devoted patron of the arts — specifically violinist-composers Arcangelo Corelli and Antonio Vivaldi. Ottoboni not only wrote the libretti for several other Scarlatti oratorios but also maintained a valuable music library. (Intriguingly, pieces of Ottoboni’s estate, including scores and parts to almost a hundred compositions, ended up in England; several came into possession of Charles Jennens, the librettist for Handel’s Messiah.)

Dirst describes the work as “a mixture of the heavenly with the playful. Its subject matter — divine love — found a perfect compositional partner in Alessandro Scarlatti, the great master of the Italian vocal style at the dawn of the eighteenth century.”

The four solo roles for this version feature three countertenors as Sposo, Amor, and Eternità, and a soprano as Sposa. In describing the vocal writing, Dirst writes, “Scarlatti underlines the hierarchy of characters in La sposa dei cantici by assigning both leads to sopranos and the two supporting roles to altos. Castrati probably sang all these parts originally, including the high-flying role of Sposo since that character effectively plays God. The unearthly sound of a soprano castrato — who sang with the power and agility of a man but in the range of a woman — fascinated Italians especially during the long Baroque age.”

Ars Lyrica Houston has fared well in casting these parts, especially with the choice of the extremely gifted countertenor, John Holiday, who easily traverses the role’s required range, both dramatic and vocal, in a persuasive performance. His heroic rendition of the bravura aria, “Non fidarti del tuo ciglio” is matched only by his sensitive recitative singing, managing the vocal heights without a hint of strain.

Holiday is well matched by Canadian soprano Meghan Lindsay, whose introductory aria, “Se la fiamma,” has a string figuration that a connoisseur of Handel’s oratorios might find familiar: a violin accompanying-figure that found its way into his 1749 oratorio, Theodora, in the alternating allegro-sections of Didymus’ Act I aria, “Kind Heav’n.” This connection is interesting to hear, written years before Handel’s own experience with Italian oratorio in Rome and yet showing a possibly much later influence (and abiding appreciation for Scarlatti) in this Handelian “borrowing.”

The other two countertenor roles of Amor (Cupid) and Eternità round out with their “color-commentary” in both solo arias and clever duet-forms the convoluted “story” of a Dialogue between a soul and God. American countertenor Jay Carter shines in Amor’s vocally resplendent scenes.

What makes this “sacred” pseudo-drama work is Scarlatti’s melodic and orchestral inventiveness, his ability to bring human qualities and expression to these intentionally marble-sculpted singing statues. At some points he conjures the expressive power of Monteverdi’s emotionally heightened repeated text (as in Sposa’s Part II recitative, “Vi son pur giunta, oh cara, cara, cara”) and, elsewhere, he pre-figures Gluck’s dark display of the underworld, such as in the brief orchestral introduction to Sposa’s Euridice-like nightmare, marked “Orrido.”

Scarlatti’s infinite variety of orchestral colors — especially given the demands of writing for strings only — is on full display, from the concerto grosso-style opening Sinfonia to the clever use of a solo cello obbligato (in Amor’s Part I aria, “Al lieto grido” and Sposo’s Part II aria, “Vieni, vieni, e porta al Cielo”) to indications of “senza cembalo” (without keyboard) in some of the colorful accompagnato recitatives.

Most noteworthy though is Scarlatti’s gift in creating an imminently singable line in music naturally wedded to the Italian language. It is a melodic language that is logical and deceptively simple, able to accommodate an expected (and inevitable) ornamentation. Indeed, given his compositional facility and immense output, he could be remembered — along with Rossini — as being able to set a laundry-list to music.

This new recording, released in September 2023, was recorded back in February 2014 in Zilkha Hall in the Hobby Center for the Performing Arts in Houston. Dirst brilliantly brings all it to life throughout, in masterful choices of continuo groupings (reserving harp and organ mostly for Amor; harpsichord for Sposa/Sposo) and in a clever use of pizzicato accompaniment (for Sposa’s Part II aria, “Fortunati miei sospiri”).

While a 90-minute string of 18th century da capo arias in a static setting may seem no different (and no less dry) than opera seria, Ars Lyrica Houston, in this historically informed and compelling performance of La Sposa, make a strong case for this rarely heard work.

Jeffrey Baxter is a retired Choral Administrator of the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, where he managed and sang in its all-volunteer chorus and was an assistant to Robert Shaw in his final years. He holds a doctorate in choral music from The College-Conservatory of Music of the University of Cincinnati and has written for BACH – The Journal of the Riemenschneider Bach Institute, The Choral Journal, and ArtsATL. For Early Music America, he recently reviewed the Washington Bach Consort in music by Trevor Weston and J.S. Bach.