by Mark Kroll

Published February 13, 2023

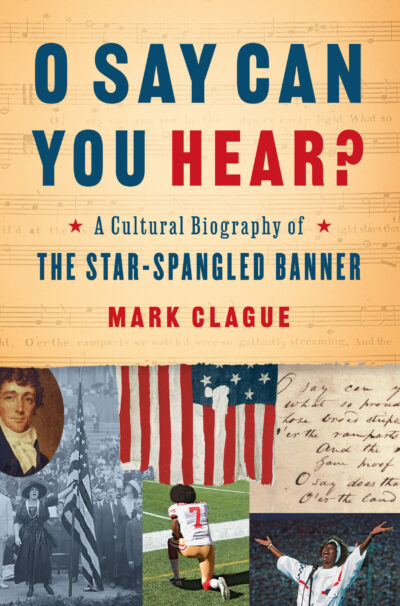

O Say Can you Hear? A Cultural Biography of the Star-Spangled Banner by Mark Clague. W.W. Norton, 2022. 325 pages.

Who wrote the words to the Star-Spangled Banner, when were they written, and why? Where did the music come from, and why do people claim that the melody is so difficult to sing? How and when did it actually become our national anthem? Is it a source of conflict and division, or can it still serve to unify the nation, if it ever really did? These are just a few of the questions Mark Clague poses in the prologue to his excellent “cultural biography” of the Star-Spangled Banner, and he answers them with an evenhanded approach and solid scholarship.

Who wrote the words to the Star-Spangled Banner, when were they written, and why? Where did the music come from, and why do people claim that the melody is so difficult to sing? How and when did it actually become our national anthem? Is it a source of conflict and division, or can it still serve to unify the nation, if it ever really did? These are just a few of the questions Mark Clague poses in the prologue to his excellent “cultural biography” of the Star-Spangled Banner, and he answers them with an evenhanded approach and solid scholarship.

The origins of Francis Scott Key’s poem are well known to most Americans…or are they? Key wrote the poem while held captive by the British during the Battle of Baltimore in 1814 (part of the War of 1812), but this reviewer did not know that he was captured while on a mission to negotiate the release of another prisoner, Dr. William Beanes, an American physician and surgeon who had been taken into British custody after the burning of Washington.

The “banner” that so proudly waved is a story in itself. The commanding officer of Fort McHenry in Baltimore, Major George Armistead, ordered “a flag so large that the British will have no difficulty in seeing it from a distance.” He succeeded: it measured 30-by-42 feet, the largest used during the war. Those involved with Fort McHenry’s defensive works were equally notable: “all free people of color” were ordered to assist in their construction, for a “soldier’s rations.”

The author provides a cogent analysis of the music to which Key set the lyrics, including the origin of that reportedly unsingable melody, To Anacreon in Heaven, composed by the Englishman John Stafford Smith in about 1773 as the club anthem of the Anacreontic Society of London, and brought to Philadelphia by a touring theater group in 1793. We also learn that the Star-Spangled Banner did not become our official national anthem until March 3, 1931, when President Herbert Hoover signed into law the bill passed by Congress.

Clague, a musicologist and specialist in American culture at the University of Michigan, pulls no punches by pointing out that this anthem of ours has been plagued from its very beginnings by a number of negative connotations, racism in particular. The phrase “hireling and slave” in the third of four verses (we only sing the first) is certainly problematic, but the author explains that “hirelings” referred “to British enemy soldiers, specifically Redcoat regulars,” and “slaves” were Colonial Marines who had escaped slavery in the United States “and then volunteered to fight with the British” during the war. Clague remind us that Key did own slaves, but adds that he became a staunch abolitionist who freed them in 1811, writing that slavery was a “great moral and political evil…inhuman… abominable and detestable beyond all epithets.”

Nevertheless, racist overtones became attached to the banner from the outset and have never left it. When the football quarterback Colin Kaepernick took a knee during the Star-Spangled Banner in 2016 in protest against racism, his was not a new or unique expression of outrage. More 150 years earlier, in December 1860, an unnamed Black woman wrote about a charity concert given for the benefit of Boston’s Joy Street Baptist Church and its abolitionist minister, the escaped slave John Stella Martin: “the Star-Spangled Banner…grated harshly upon my ears” because “this song always appears to me to be out of place when sung by colored people…‘O long may it wave, O’er the land of the free, and the home of the brave’ should never be pronounced by Anglo African lips, so long as a single child of God clanks a fetter upon the American soil.” She did not take a knee, but “kept [her] seat” in protest.

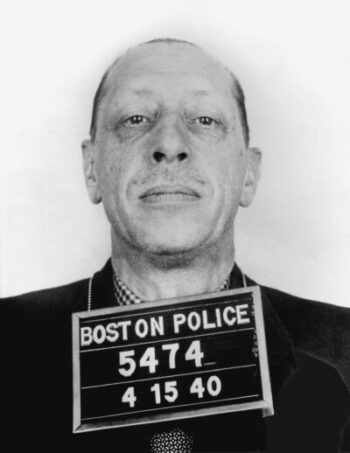

World War I was another chapter in the anthem’s use and misuse, particularly in the service of some misplaced militaristic fervor. A prime example is the fate that befell Karl Muck, conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra from 1906-1908, and 1912-1918: a series of misunderstandings about the required performance of the anthem before concerts led to Muck’s imprisonment in 1918 and ultimate deportation.

Even Igor Stravinsky was not immune to anti-immigrant hysteria, and the Boston Symphony was again involved. The performance of his own, very “Stravinskian,” arrangement on January 15, 1944 was not only criticized, but the composer had unknowingly broken a Massachusetts law of 1917 against improper versions of the anthem, punishable by a fine of up to $100.

More culturally consequential was the rendition of the Star-Spangled Banner performed by Jimi Hendrix at the Woodstock Music & Arts Fair of 1969. Clague, who devotes four pages of historical background and musical analysis to the event, calls Hendrix’s Woodstock Banner “one of the most iconic musical visions in rock history.”

The author also examines in depth the ubiquitous connection of the Banner to the world of sports, one so entrenched that the comic answer to the question “what are the final words of the Star-Spangled Banner?” is “Play Ball!”

Here World War I again became a flash point. Opening Day of the 1917 baseball season featured a mock military drill led by Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and the Chicago White Sox wore uniforms decorated with stars, flags, and spangles. 1918 marked the first time fans sang along, and Clague offers an impressive list of solo singers who have performed it since then and before every type of sporting event.

They include famous renditions by Whitney Houston (Super Bowl XXV), Aretha Franklin (before the 1987 title fight of the boxer Thomas “Hitman” Hearns, to cite just one of many examples), Diana Ross (Super Bowl XVI), and José Feliciano (1968 World Series) and an infamous version by Roseanne Barr at a 1990 San Diego Padres game that ended her career.

Clague concludes by recognizing that although Key’s song reflects “the bias and privileges of its era and its author,” he urges those who sing it today to place it within the context of America’s confrontation with racism, discrimination, inequality, and militarism. He cautions, moreover, that despite all of the anthem’s “fantasies and flaws,” it should not be replaced because this “would discard the power of history” and prevent us from using the Star-Spangled Banner “as a compass navigating toward a more constructive future.”

A second, revised edition of Mark Kroll’s biography of Johann Nepomuk Hummel will be published this year by Hudobné Centrum (Music Centre Slovakia) of Bratislava in both a Slovakian translation and an English-language E-Book.