by John Koster

Published July 15, 2024

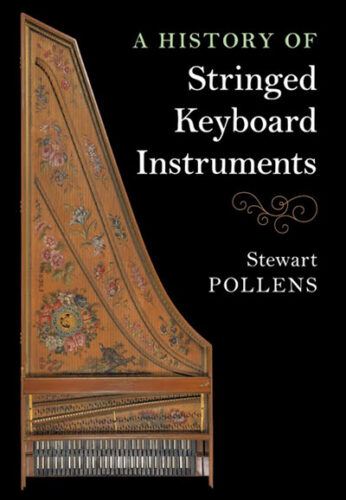

A History of Stringed Keyboard Instruments by Stewart Pollens. Cambridge University Press, 2022. xix + 571 pages.

With the rise of historically informed performance, scholarly research into clavichords, harpsichords, and pianos has resulted in countless publications, each usually devoted to a particular type or genre. Historical instrument makers and players, however, commonly dealt with all the types current in their time and place, often interchangeably. Thus, to produce an integrated history of all stringed keyboards is a laudable goal for which Stewart Pollens, a noted scholar and restorer of early instruments, should be ideally suited.

At the outset he states his intention to write for “those who play or otherwise enjoy keyboard instruments, rather than those who make, restore, and collect them” and “to explain the principles of their design and construction and to explore the relationship between keyboard instruments and the composers and virtuosi who played them.” He focuses on the “principal types” that are “used or preferred by major composers.”

The book is beset with numerous problems. Start with the one that the author has the least control over: the choice and quality of the illustrations. There are 94 of them, but the selection is poor and many are barely larger than thumbnails. A futile five-page discussion of early-keyboard compasses, for example, is centered around eight images derived from the botched woodcuts published by Sebastian Virdung in 1511 and Martin Agricola in 1528. The section titled “Flemish and Antwerp-school Keyboard Instruments,” which deserves extensive discussion but covers less than two pages, features one minuscule picture of a double virginal by Hans Ruckers. Ruckers single-manual harpsichords go unmentioned here, while the description of the standard doubles of this great instrument-making dynasty could well have been illuminated by a picture of their notable transposing keyboards.

Pollens’ text can be just as problematic. Turning to Renaissance Italy, more than half of the nearly nine pages dealing with this subject discuss documents from 1598 concerning instrumenti pian e forte. Whatever these were, possibly with a hammer action but perhaps just normal harpsichords with convenient levers or pedals to change the stops, they were not representative. The space could have been better used to describe and illustrate the varying types of harpsichords and virginals from such major centers as Venice, Naples, and Milan.

The coverage of Germanic harpsichords before the 18th century is especially deficient, amounting to the description of one instrument by Hans Müller, Leipzig, 1537. Much of the treatment of this important harpsichord is an effort to discredit the authenticity of its soundboard, which Pollens believes is a replacement made in Italy because it is cypress, deemed unlikely to have been used in Germany. (Evidently he forgot his own 2001 article describing a virginal made by Lorenz Hauslaib of Nuremberg in 1598 with a cypress soundboard.) Seventeenth-century Germanic harpsichords, with their distinctive dispositions often including close-plucking nasal stops, are bypassed entirely.

The book’s haphazard structure is exemplified by Chapter 5, “The Baroque Period,” in which Ruckers harpsichords, made before the 1650s and barely discussed in Chapter 4, are again briefly taken up. But this comes only after discussion of various subjects, including the instruments played by 18th-century French composers, followed by a discussion of Jacques Champion de Chambonnières, who died in 1672. After Ruckers, the chapter returns to 17th-century French harpsichords in a brief treatment that fails almost completely to take into consideration anything discovered since Frank Hubbard wrote about them in 1965. It might at least have been useful to note that the keys of early French harpsichords are quite narrow, facilitating the wide stretches found in Chambonnières’s works. After a cursory treatment of Louis XIV’s France, Chapter 5 turns to sections successively about J.S. Bach, Handel, English instruments including virginals made as early as 1641, and concluding with Domenico Scarlatti. Reader, beware of whiplash!

In the case of Scarlatti, Pollens’ neglect of what has been learned about harpsichords in Scarlatti’s Portuguese and Spanish environs is inexcusable. Bach fares only a little better, with a strained attempt to push Gottfried Silbermann’s involvement with piano making — hence Bach’s possible familiarity with the new instrument — as far back as 1726 or even 1720. Curiously, in a later chapter, Pollens more reasonably states that Silbermann made his first pianos in the early 1730s. Regarding Bach’s harpsichords, the author opines that the relevance of 16-foot stops to the performance of his works is “debatable.” Any debate, however, should not have omitted the evidence of an advertisement in a Leipzig newspaper in 1775 for a veneered 16-foot harpsichord made by Zacharias Hildebrandt, who, active in Leipzig from the mid-1730s to 1750, was closely associated with Bach.

Pollens’ admirable research on the pianos of the instrument’s inventor, Bartolomeo Cristofori, has resulted in two previous books and a large section in the present volume. The intensity of his interest in this aspect of the early piano, however, would seem to have led to a jaundiced view of the parallel strand of development beginning in Germany with efforts to make “pantaleons,” keyboard instruments inspired by the hammered dulcimer playing of Pantaleon Hebenstreit.

Characterized by bare wooden hammers yielding a loud, bright sound, often moderated by a stop interposing strips of cloth or leather, without dampers or with dampers that could be disengaged, this strand has been explored by other prominent scholars, but Pollens dismisses them at the outset as “musical oddities.” Thus the keyboard pantaleon by Wahlfried Ficker, for example, advertised in Leipzig in 1731, passes unmentioned, even though Bach’s first encounter with a hammer-action keyboard might have been with this Cymbal-Clavier, “in the form of a 16-foot harpsichord” with “the character of the Cymbel invented by the famous Pandalon.” In any case, it is obvious that the modern damper pedal, “the soul of the piano,” was derived from the pantaleon.

Pollens’ dismissal of this type of instrument is made all the more incomprehensible by the fact that keyed pantaleons remained in use by serious musicians into the early Classical period. Mozart, in a well-known letter about his first encounter with the pianos of J.A. Stein in 1777, mentions that until then he preferred those of Frantz Jacob Spath.

These would presumably include one built by Spath in 1767 that is identifiable as one of the Pandaleons-Clavecins advertised in 1765. Housed in a prominent American museum since 2006, Pollens does not mention it.

He also conflates the simple damperless types of keyed pantaleons with their more sophisticated offspring, square pianos with dampers, one of which Mozart recommended to a cherished benefactor, while another was likely the only piano in C.P.E. Bach’s estate. Such instruments merit serious attention. Fortunately, the author’s treatment of Stein’s and Anton Walter’s grand pianos and their relationship to Mozart is adequate. Michael Latcham’s pathbreaking research into the work of these makers is duly considered, although Pollens disagrees with some of his conclusions.

Although conceived by an author with a great passion for his subject, this book — bewilderingly structured, factually deficient, stubbornly blinkered, carelessly edited, and poorly illustrated — falls far short of the standard one expects from a serious scholar. The author reveals an unfortunate hubris in his preface, stating that “I have rarely sought or received advice, nor have I ever had drafts reviewed by colleagues.” He would have been well-advised to rethink his approach to serious, peer-reviewed scholarship.

John Koster, after studying musicology at Harvard College, was a harpsichord maker for 20 years. Author of Keyboard Musical Instruments in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, he was professor and curator at the National Music Museum, University of South Dakota, from 1991 to 2015.

UPDATE August 12, 2024: Author Stewart Pollens replied to this review with a Letter to the Editor.