by

Published September 23, 2016

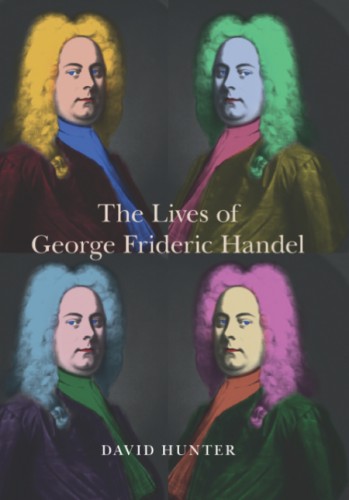

The Lives of George Frideric Handel. David Hunter.

Boydell and Brewer, 2015. 536 pages.

By Mark Kroll

BOOK REVIEW — Do we really need another biography of George Frideric Handel? This latest entry in the extensive literature about the iconic composer asks that very question on the book jacket, and answers it before you get to the title page: “To evaluate the familiar, even over-familiar, story of Handel’s life could be seen as a quixotic endeavor. How can there be anything new to say? David Hunter’s book seeks to distinguish fact from fiction, not only to produce a new biography but also to explore the concepts of biography and dissemination by using Handel’s life and lives as a case study.”

The Lives of George Frideric Handel more than accomplishes its goals. Well-written, richly documented, and colorfully presented, Hunter’s unique spin on what we know about Handel, or thought we knew, is a valuable addition to the early-music library.

You sense you are in for an exciting ride just by scanning the table of contents. Chapters such as “The Audience: Three Broad Categories, Three Gross Errors,” “Musicians and other Occupational Hazards,” and “Self and Health” are not standard fare in most musicological studies. Nor is Hunter’s description of his methodology in the preface: “Instead of a chronological sequence, the chapters enact a Möbius strip, by which, at the end, we have looked not only at what biographers have said about events but also at the biographers themselves. Handel’s life and lives and their story-tellers will be seen from new angles but as part of a continuous whole.”

You sense you are in for an exciting ride just by scanning the table of contents. Chapters such as “The Audience: Three Broad Categories, Three Gross Errors,” “Musicians and other Occupational Hazards,” and “Self and Health” are not standard fare in most musicological studies. Nor is Hunter’s description of his methodology in the preface: “Instead of a chronological sequence, the chapters enact a Möbius strip, by which, at the end, we have looked not only at what biographers have said about events but also at the biographers themselves. Handel’s life and lives and their story-tellers will be seen from new angles but as part of a continuous whole.”

Hunter does not disappoint. He deals with such issues as gender, religion, sexual orientation, “patrons and pensions,” musical performances, Handel’s finances, and his health, while at the same time taking on his fellow scribes with sections titled “When Biographers Fight” and “Plot Types and Biographical Story-Telling.”

For example, Hunter questions the long-held claim that Handel’s oratorios — Judas Maccabaeus, in particular — depended on the support of the Jews living in London at the time, asking: “Who were the Jews who attended performances of Handel’s works and subscribed to his publications? Did Jews think that Handel supported them? Was it only on commercial grounds that Handel was concerned about the absence of Jews from his audience, as one librettist reported? To what extent did the presence of Jews affect the way he and his librettists crafted their entertainments?”

Hunter’s answer is typically blunt and revealing. He begins by estimating that “perhaps twenty-six to thirty-nine families had the required wealth” to support Handel’s efforts, and adds further evidence that the influence of the Jews could not have been large, in any event, since performances of the oratorios in the 1740s were usually “on Wednesday and Friday nights. Not only would observant Jews be unwilling to attend on Friday evenings, they would also find Passover a trifle inconvenient!”

One of the more interesting sections deals in depth with the public rehearsal of Handel’s Music for the Royal Fireworks at Vauxhall Gardens in April 1749 that 12,000 people reportedly attended. Hunter debunks this number from a variety of perspectives. One is the actual size of the Gardens, which he gives in feet, inches, and acres, concluding that they could not have physically accommodated so many people.

Another was the problem of transporting such a crowd from London to Vauxhall in time for the performance, citing what seems to have been the mother of all traffic jams, as Hunter colorfully describes: “On the day of the…rehearsal, a near three-hour stoppage on London Bridge was caused by the mass of coaches en route to Vauxhall.” It was, the Penny London Post noted, “a thing not known before in the Memory of Man.” Based on this and other evidence, Hunter convincingly estimates that not 12,000, but “approximately 3,000 people could have been accommodated in the vicinity of the rehearsal.”

Handel’s financial situation is covered in detail, including a section titled “Supposed Bankruptcy and Actual Wealth,” in which we learn that Handel profited greatly from his investments in the slave trade. Hunter also concludes that claims Handel “was the first musician to break free of elite patronage are bogus,” citing the fact that “Handel was cushioned from the dire consequences of the market turning against him thanks to the support of one of the richest families in the land: the Hanoverian monarchs.” As the author succinctly puts it, “The middle-class audience is a chimera.”

There is much more, including sections on Handel’s “Paralysis and Other Health Problems,” “Biographers’ Approaches to Corpulence and Gluttony,” and “An Eating Disorder Diagnosis,” which Hunter dubs “binge eating disorder.” He also believes there is not enough evidence on which to base a definitive conclusion about Handel’s supposed homosexuality.

Hunter concludes the book with an honest observation: “Every biographer has something to say but none, even this one, can have the last word.” This might be true, but the words in this book are well worth reading.

Mark Kroll, professor emeritus at Boston University, is a harpsichordist, fortepianist, scholar, and educator. His publications include editions of the music of Hummel, Geminiani, Avison, and Francesco Scarlatti, and books about the harpsichord, the Beethoven violin sonatas, and Ignaz Moscheles.