by Valerie Walden

Published July 18, 2022

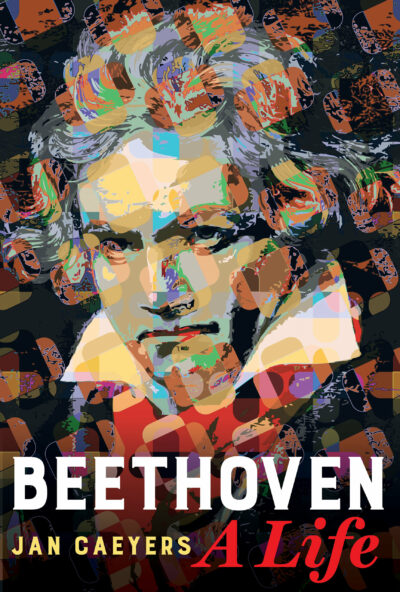

Beethoven: A Life by Jan Caeyers, University of California Press, 2020, 630 pages.

This fascinating approach to Beethoven’s life and works, by conductor and scholar Jan Caeyers, was first published in Dutch in 2009 and has only recently appeared in the excellent English translation by Brent Annable. A charming read, the book tells the story of Beethoven’s transformative career in almost operatic terms, with a cast of characters that provides not only the dramatic details of Beethoven’s life, but also offers subplots that vividly transport the reader into the worlds of late 18th- and early 19th-century Bonn and Vienna.

The book is organized into five parts, the first devoted to 1770-1792. We are introduced to members of Beethoven’s family going back to the 1720s. Then come the cast members of his childhood, such as his principal teacher, Christian Gottlob Neefe, plus dramatic personae like Count Belderbushe, Franz Ries, the Breuning family, Franz Wegeler, and Count Waldstein.

The second part, spanning the period 1792-1802, describes Beethoven’s first years in Vienna, where we meet his teachers, Haydn, Albrechtsburger, and Salieri, the patrons Lichnowsky and Lobkowitz, “the disciples” Carl Czerny and Franz Ries, his archrival and friend J. N. Hummel, and the numerous ladies whom Beethoven was attracted to and who, at least in some instances, returned his affections. This book is also replete with fun facts that bring to life Beethoven’s Viennese world. There is a delicious amount of gossip about the individuals with whom Beethoven came into contact, male and female, and we learn many interesting details, such as the fact that Vienna had more piano teachers than doctors at this time.

Parts three and four explore Beethoven as an established and creative force. His personal and working associations are discussed, the natures of the publishing world and piano industry are explained in easy-to-follow detail, and Caeyers also examines the history and compositional strategies of the major works written during this time, with special attention given to the Eroica Symphony; the Appassionata Sonata; and Fidelio. The ongoing dramatic saga of this section is, however, the “Immortal Beloved,” as Beethoven dubbed her, Caeyers believing that the mystery lady was Josephine Deym (nee von Brunsvik), whose sad biography is another interesting component to this book. Widowed with four children at age 25 and miserable in her second marriage, she died at 42, impoverished and abandoned by her husband and aristocratic family.

Part five, the final act of Beethoven’s life and career, covers the years 1816-1827. It includes Beethoven’s complicated relationship with his nephew, Karl; the last compositions, especially the Missa Solemnis; the late piano works; the Ninth Symphony; and the string quartets, opp. 127, 130, 131, 132, and 135; all followed by Beethoven’s illness and death.

Photo: Marco Borggreve

Caeyers, as he did with chosen works in the earlier sections of the book, analyzes these pieces, places them in their historical context, and offers his personal insights into possible performance practices. His discussion about the history of the metronome and appropriate tempos is particularly thorough.

Beethoven the misanthrope is also discussed here, and personal secretaries Karl Holz and Anton Schindler are portrayed respectively as hero and fool. Beethoven’s last days are also covered in graphic detail, including the names and quantities of alcohol delivered to Beethoven and consumed during his deathwatch, and the gruesome surgical practices employed for his palliative care. Caeyers’ research reinforces the belief that Beethoven was indeed an alcoholic and suggests that by the end of his life, he was also diabetic.

Nevertheless, for all the fascinating information found in this book, it sometimes reads as a disconnected series of essays with an occasional repetition of material. Several points are either contradictory or questionable. One is Caeyers’s opinion that the cause of Beethoven’s hearing loss was murine typhus, the author first stating this as an absolute, because Beethoven contracted typhus in Vienna in 1796, but later softening his opinion slightly by noting that there is a lengthy list of possible diagnoses for Beethoven’s deafness, admitting that “establishing a correct diagnosis nearly two hundred years after a patient’s death is a task verging on the impossible.”

A few facts, moreover, are simply incorrect. A prime example is his description of some members of the Romberg family, who were notable musicians in the Bonn court of Beethoven’s childhood, particularly the cousins Andreas (a violinist) and Bernard (a cellist), who went on to have remarkable performance and publishing careers. Caeyers mistakenly states that they were both brothers and cellists.

Of equal import are the inconsistencies regarding the conventional belief about Beethoven’s childhood poverty. Caeyers first states that Beethoven’s grandfather, Jean, lived comfortably from inherited money, concluding that “the traditional belief that Ludwig van Beethoven grew up in poverty is therefore romanticized and inaccurate.” However, he later tells us that the Bonn court evaluated the young Ludwig as “young, talented…and…quite poor,” and that Ludwig’s father, Louis, following his wife’s death, was in such dire financial straits that he had to sell his deceased wife’s clothing on the second-hand market.

These quibbles aside, Caeyers’ expertise with both the social history of Beethoven’s world and the music of the period makes this an important addition to the Beethoven literature. In it we learn more of what we already know about the great composer, and much that we did not know, adding to our understanding and appreciation of this pivotal figure in musical history.

Valerie Walden maintains an active cello studio and serves as the principal cellist of the Sequoia Symphony. The Japanese translation of Dr. Walden’s One Hundred Years of Violoncello: A History of Technique and Performance Practice, 1740-1840 (Cambridge University Press, 2004) has recently been published.

More Book Reviews: