by Sophie Genevieve Lowe

Published June 19, 2023

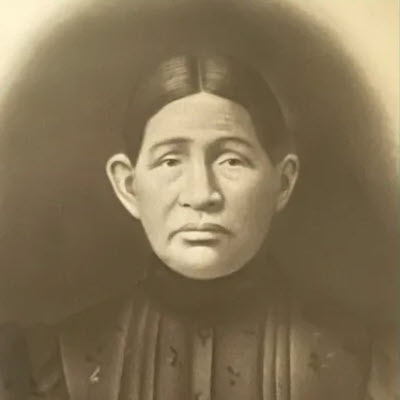

Occramer Marycoo, the man called Newport Gardner

His life is essential to understanding early music in America

In January 2023, Sotheby’s held an auction for a Chippendale chest of drawers, estimated to sell for almost $800,000. Part of its unusually high value derived from the original owner, which Sotheby’s advertised as the “Important Lieutenant Colonel Caleb Gardner” — a hero of the American Revolution and friend to George Washington. Sotheby’s omits that Gardner helped enslave some 3,912 human beings, one of whom was Occramer Marycoo, perhaps the first Black African to have music published in America and the first Black musician to be recognized by the white American community as a professional musician.

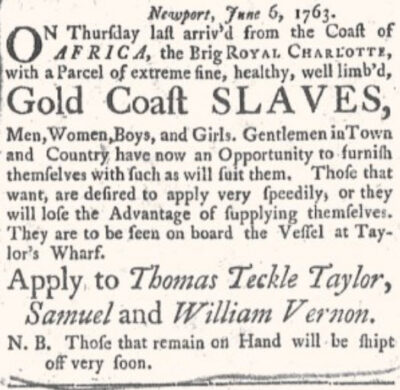

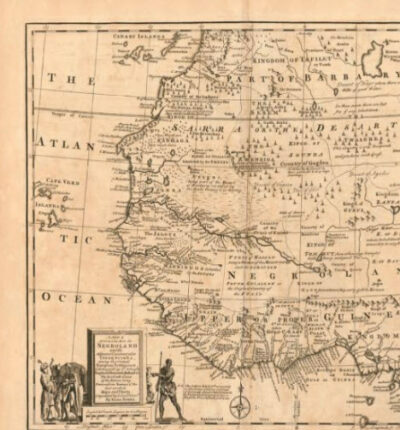

Occramer Marycoo’s story commences and concludes in Africa. Yet the bulk of his life was spent across the Atlantic. Young Marycoo shared his horrific ordeal with the 10.7 million people who suffered in the transatlantic slave trade to America. Based on the spelling of his name, it is likely that Marycoo was from an Akan language people group from the Gold Coast of Africa, specifically Ghana.

Marycoo was forcibly transported to the American colonies, possibly on the 1764 voyage of the ship “The Elizabeth,” owned by sea captain Caleb Gardner. Records from the Transatlantic Slave Database show that the ship left Cape Coast, a prison fort in Ghana, with 120 captives on board. Only 89 survived the crossing.

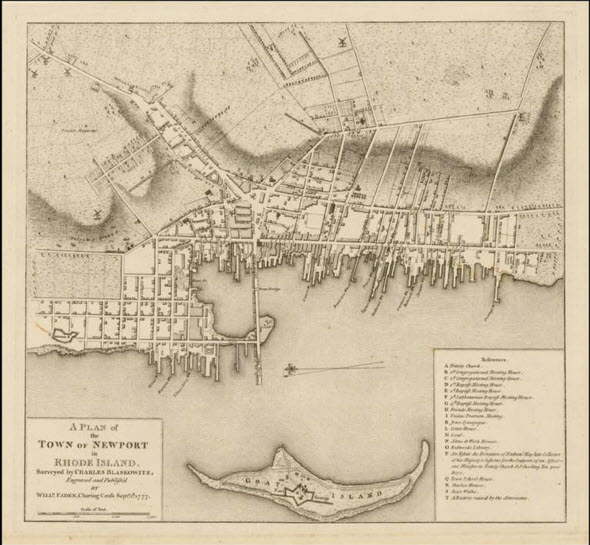

Although the majority of enslaved people who were brought to Newport, Rhode Island were eventually shipped to the Caribbean, Gardner kept Marycoo as his own property, renaming him Newport Gardner. He is thought to have been around 14 years old when brought to America and, throughout his life, he would go by both names. However, since Newport Gardner is the name given to him as an enslaved person, this article will continue to call him by his given name, Occramer Marycoo (sometimes spelled Occramar).

The first slaves were brought to Rhode Island most likely in 1649 aboard a boat unfortunately named The Beginning. Throughout most of the 18th century, Newport was the largest slave trading post in North America.

It was not long after arriving in Newport that Marycoo displayed his brilliant intellect. He quickly became fluent in English and French and learned the fundamentals of music. He was said to be composing within four years of his arrival in America. There are several theories as to who taught Marycoo, the most prominent being American composer Andrew Law (1749–1821). Law wrote much about music education, including Select Harmony (1778), The Art of Singing (1780), and Rudiments of Music (1785).

Scholarship into Marycoo is a relatively new field considering his importance in history. There are numerous references to compositions by Marycoo, but his only known surviving work is the crux of Marycoo’s historical place as the first published musical work by a Black person in the nascent United States. Musicologist Eileen Southern, in her 1997 book The Music of Black Americans: A History, theorized that “Crooked Shanks,” from a collection called A Number of Original Airs, Duetto’s, and Trio’s [sic], published in 1803, was by Marycoo. The piece is credited to a composer with only the last name given, Gardner.

However, new research seems to indicate that the music had been composed prior to the 1803 publication date. “Crooked Shanks” was also previously published in London under the title “The Sea Side” by the publisher Bride in Twenty Four Country Dances for the Year 1768, and in the 1770s, as the “The Bill of Rights” by the publisher Thompson.

John Fitzhugh Millar identified both these melodies in his book Country Dances of Colonial America. He also believes that Marycoo wrote this melody and goes as far to hypothesize that Marycoo also listed the dance instructions that accompany the melody. Marycoo’s status as a slave would have certainly been a deterrent to properly credit him at the time — if he indeed wrote the piece. Lamentably, like so many others who were held in bondage and under institutionalized racism, it is difficult to historically ascertain much of Marycoo’s life and achievements. Even if the piece is not by Marycoo, it doesn’t diminish the fact that he was breaking ground simply to be regarded as an actual composer — a Black composer — in colonial America.

We can gather clues to some of Marycoo’s musical influences. As a composer and teacher, Law dedicated himself to forging an American musical style based on European traditions. That element is found in Marycoo’s short but delightful “Crooked Shanks.” Although more scholarship may uncover earlier published compositions by Marycoo, as of now “Crooked Shanks” stands as the first attributed published piece of music by a Black composer in the European style in the United States.

Many sources point to Law as the most likely teacher to Marycoo. The problem is that the first known time that Law went to Rhode Island was in 1783, when Marycoo was already in his late thirties. By then, Marycoo had already composed his first known work, an anthem based on text from the biblical Book of Jeremiah, on or before 1764.

An earlier teacher could have been the composer Josiah Flagg (1737-1794). Flagg was also a publisher and, in collaboration with Paul Revere, published a collection of psalm tunes in 1764, the same year as Marycoo’s anthem. Marycoo’s anthem was used in worship until at least 1940 at the Union Congregational Church in Newport, though it now appears lost. In all likelihood, Marycoo probably had a variety of musical teachers in America.

A Dream to Return Home

As Marycoo approached his own musical identity, he would no doubt have been influenced by African musical traditions. West Africa had a rich history of musical instruments, for example the lute had been in West Africa since the 14th century. There is also the possibility he was a part of the jilikea or “singing men.” These men were from an aristocratic family who were used by royalty to recall history, perhaps similar to the troubadours of Europe.

We perhaps have a glimpse of the musical life of Marycoo from his contemporary, Olaudah Equiano (1745-1797), a man who was also from West Africa and enslaved in America before purchasing his freedom. He went on to write about his experiences and recalled life in West Africa:

“We are a nation of dancers, musicians, and poets. Thus every great event, such as a triumphant return from battle, or other cause of public rejoicing in public dances, which are accompanied with songs and music suited to the occasion…we have many musical instruments.”

It is fascinating to note that the Akan word for master drummer, okyerema, may have become the phonetic spelling of Occramar in English. There survives quite a few observations about Marycoo’s abilities, including his “very superior powers of mind” and that he was “well acquainted with the science and art of music.” Marycoo did not forget his mother tongue: there are accounts of him speaking to fellow enslaved Africans who had recently arrived.

The desire to make the return Atlantic crossing seemed to be perpetually on Marycoo’s mind. Beginning in the 1780s, the Free African Union Society became a focal point of the Black community in Newport. The core of the organization was to gain freedom and emigrate back to Africa. To that end, the society also pooled money to buy lottery tickets for members. In 1791 Marycoo joined a lottery and the winnings enabled him to buy his freedom.

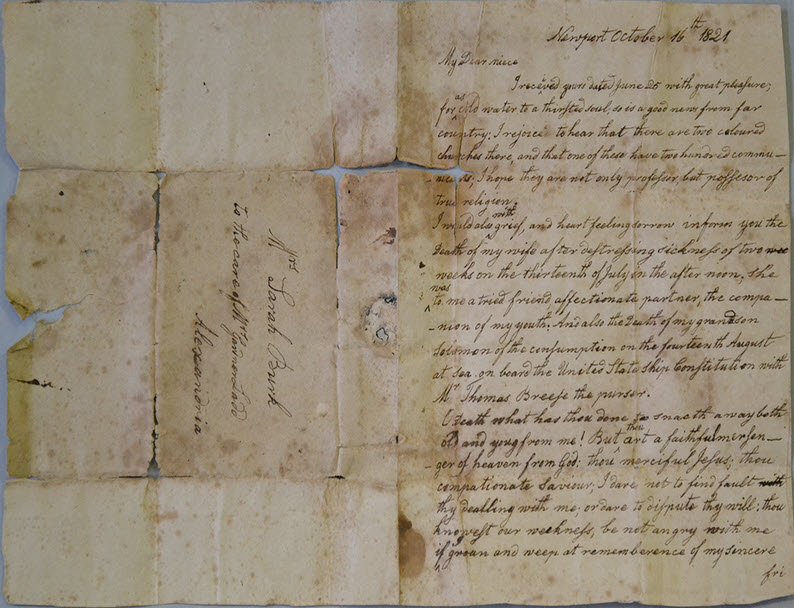

Yet Marycoo’s wife, Limas, and their eight children were still enslaved. Friends from Marycoo’s church led by Dr. Samuel Hopkins (a protégé of the Great Awakening pastor Jonathan Edwards), urged Marycoo that they would fast with him to pray for his family’s deliverance. According to various memoirs, on the very day that Marycoo and his friends prayed and fasted, Gardner called in Marycoo and said he decided to manumit his family.

Industrious in all his working endeavors, Marycoo was able to purchase his own home by 1807. Like contemporary musicians in America, such as William Billings (1746-1800), Marycoo was only a part-time musician. Besides composing, Marycoo opened a singing school in Newport. One student remembered that Marycoo had a “cane with an ivory head” to discipline students who misbehaved and that he used a pitch pipe to start the singing.”

Although he built a thriving life in Newport, Marycoo longed to return to Africa as a missionary with members of his church. After years of preparation, a special service was held to send them on their voyage. Notably, the service closed with an anthem composed by Marycoo. Although the music has been lost, the words were recorded by a Boston newspaper and became popular:

“Hear the words of the LORD, O ye African race. Hear the words of promise.”

Perhaps it was the last time Marycoo heard his music played as he followed that promise on January 4, 1826. Nine days later, the Boston Recorder and Telegraph advertised a musical work called the Promise Anthem, by “Deacon Newport Gardner, a native of Africa.” There are varying reports on what happened to the members of the Atlantic voyage. Some reported that the group reached Africa and survived six months. Recent scholarship suggests that by the time the advertisement was placed, Marycoo was already dead.

Many historians reflect on how the end of Marycoo’s life seemed like a failed dream. However, this seems to be a shortsighted assessment. Marycoo lived a staggeringly successful life that transcended unimaginable horrors. He is also notable because he is one of only a handful of formerly enslaved people known to have been able to attempt a journey back to Africa. As an elderly man who understood the peril of crossing the Atlantic, just to get on that ship home was to fulfill part of his dream.

Centuries later, the story of Marycoo is one that is not widely known, taught or celebrated. Time and systemic racism have swept his music and story away. Yet his life is essential to understanding early music in America and it’s one that desperately needs more research to find and publish his music. Marycoo lived a complex life, a fusion of his native Africa and America. In the midst of a culture and young nation based on hereditary slavery, Marycoo forged his own path while keeping his own identity. That intensely independent spirit can be heard in “Crooked Shanks” and, hopefully, in soon-to-be discovered music by the man called Newport Gardner, Occramer Marycoo.

Sophie Genevieve Lowe is a Baroque violinist and graduate of the Royal Academy of Music in London, England. She is an avid researcher and performer of early music in Colonial America.

This essay is part of the series Early Music: the Americas presented by EMA’s Emerging Professional Leadership Council.

Others in the series: