by Jeffrey Baxter

Published March 2, 2025

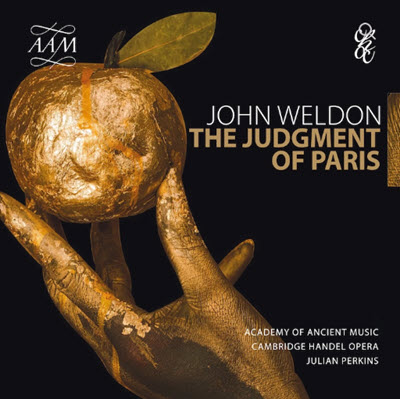

John Weldon: The Judgment of Paris. Academy of Ancient Music, conducted by Julian Perkins. AAM Records AAM046

In early 18th-century Britain, a group of aristocrats interested in promoting opera sung in English organized a music competition. They were particularly interested in an all-sung work, without the prevailing mix of music and spoken dialogue. An announcement appeared in the London Gazette on March 18, 1700, offering a “Musick Prize” for the best setting of poet William Congreve’s brief libretto, The Judgment of Paris.

Four composers threw their hats in the ring: John Weldon, John Eccles, Daniel Purcell (the younger brother of Henry), and Gottfried Finger. All four works were performed individually in 1701, then staged together in a grand finale at the Dorset Garden Theatre in June 1703. The audience judged Weldon’s work as the winner. Eccles, who was then Master of the King’s Music, was expected to win, but he came in second, with Purcell third, and Finger fourth. Eccles’ and Purcell’s scores were published by Walsh. Despite the victory, Weldon’s was never published, and Finger’s has been lost.

Julian Perkins’ engaging performance, with the Academy of Ancient Music and the Cambridge Handel Opera Company, is the first recording of Weldon’s opera. Interestingly — as recounted by Dame Emma Kirkby in the liner notes — the competition was re-staged in London in 1989, with Kirkby and the Consorte of Musicke and Concerto Köln in performances of the three surviving scores. Just as in 1703, the audience decided the winner, but in 1989 first prize went to Eccles! As Kirkby writes, the 20th-century audience was “thus re-writing history.”

John Weldon (1676-1736) was an Oxford organist and composer and student of Henry Purcell. His masques and theater-works definitely show Purcell’s influence, but as of 1701 he was demonstrating a more modern style, influenced by Italian and French forms. Some think this may be a factor in the audience’s favorable decision.

Stylistically, Weldon’s Judgment of Paris sits snugly between Purcell and Handel. It is an uneven work (due in part to the libretto), but the colorful orchestration, clever choral writing, and rapturous music for the soprano role of Venus redeem it.

The basic plot crafted by Congreve revolves around the god Mercury’s request to the shepherd-in-disguise Paris to award a golden apple (intended “for the fairest”) to one of three goddesses — Juno, Pallas, and Venus — whom he deigns most worthy. Juno offers him worldly power, Pallas military might, and Venus love from the most beautiful woman in the world (Helen of Troy). Paris gives the golden apple to Venus.

A colorful, multi-sectional Sonata of strings and winds (including oboes and trumpet) opens the work. Conductor Perkins here fills out the sonority by including high-pitched soprano recorders and a diverse basso continuo complement that includes harpsichord, theorbo, and guitar. This overture is one of several orchestral Symphonies with which Weldon frames the action throughout the work: one to introduce each of the three goddesses.

For dramatic support, Weldon also interpolates choruses by repeating text of the previous character (as in Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas and, later, Handel’s Semele). The skillfully crafted choruses provide a welcome change of color and texture, especially in the scene where Paris asks that each goddess present her case individually. Highlighting this, Perkins wisely varies the accompaniment to the choral repetition, “Let Ambition fire thy Mind,” using only winds for the second of its three instances during Juno’s solo scene in Part II.

Vocally, three of the four main roles are no doubt cast with a heroic sound in mind. Mercury (sung here by Thomas Walker), is a bold 18th-century “heldentenor” who soars up to the extremes of the tenor upper register in his opening salvo, “From high Olympus.” Juno (Helen Charlston) and Pallas (Kitty Whately) are composed for the plucky, meaty sound of the mezzo-soprano voice. Pallas is even given two attendants, cast as a soprano and baritone, who help plead her case. All are ideally represented by the gifted singers on this recording.

The stunning role of Venus (Anna Dennis) is set apart, scored for a soaring lyric soprano. It is she, with her seductive Symphonies and elegant legato lines with recorder accompaniment, who ultimately wins over Paris — and us, the listeners.

Venus’ first aria, “Hither turn thee, gentle Swain,” accompanied by a duo of dulcet alto recorders, is in ravishing contrast to the bravura Juno and Pallas. Weldon even allows her the repetition of a stanza, “Nature fram’d thee sure for Loving,” but with a dramatically slower, awe-struck, tempo that allows for vocal ornaments guaranteed to seduce Paris (and the enchanted audience).

Perkins explains in the liner notes that advice from Emma Kirkby influenced his decision to set a lower pitch for this recording (A=392Hz) — a wise choice, given the high-flung vocal writing for the soprano and tenor roles of Venus and Mercury.

Surely part of the reason for the 18th-century audience’s choice of winner stems from Weldon’s great talent for setting the English language to music. The intelligibility of the sung text is something he clearly learned from his mentor, Henry Purcell. This is heard not only in each recitative and aria, but also in the masterfully crafted choral statements where the text is presented in a mixture of independent lines that create contrapuntal interest but maintain textural clarity. The final chorus, “Hither all ye Graces,” is an excellent example and provides a rousing finale to an “opera” of static drama.

Perkins’s performance with AAM and the Cambridge Handel Opera Company is in all ways a winner — an exceptional (and exceptionally well-recorded) performance worthy of a listen. Wonderfully, the physical CD of this short, 75-minute work is packaged with an informative 70-page booklet.

Jeffrey Baxter is a retired choral administrator of the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, where he managed and sang in its all-volunteer chorus and was an assistant to Robert Shaw. He holds a doctorate in choral music from The College-Conservatory of Music of the University of Cincinnati and has written for BACH – The Journal of the Riemenschneider Bach Institute, The Choral Journal, and ArtsATL. For Early Music America, he recently reviewed Campra’s Requiem and Choral Masters of Notre Dame.