by

Published April 14, 2017

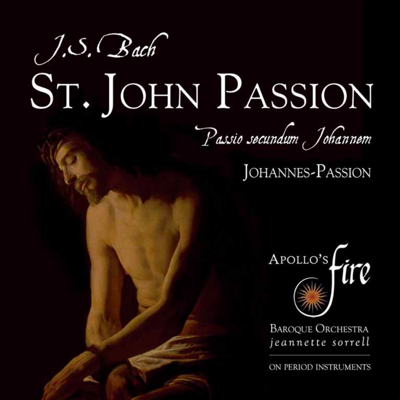

J.S. Bach: St. John Passion

Apollo’s Fire (Jeannette Sorrell, director); Nicholas Phan, Jesse Blumberg, Jeffrey Strauss, Amanda Forsythe, Terry Wey, Christian Immler; Apollo’s Singers

Avie AV2369

By Karen Cook

CD REVIEW — Johann Sebastian Bach’s St. John Passion was first performed on Good Friday, April 7, 1724. He wrote the work, at the age of 39, a year after he moved to Leipzig to take over duties at St. Nicholas Church, where the piece was first performed, and three other local churches. St. John Passion was one of the first works Bach composed in a creative whirlwind that would last well into the next decade. Bach’s Passions are probably the most well known of their genre — he wrote St. Matthew Passion a scant three years later — but the idea of setting the Gospel stories depicting the trial and crucifixion of Jesus in the manner of a Lutheran oratorio had developed a century earlier, and Bach’s more famous contemporaries also took their turns with the genre.

As was the custom, Passion settings were split into two halves so that a sermon could be given in the middle. Part I here, based on John 18:1–27, sets two main scenes — Jesus’s arrest and Peter’s denial — while Part II sets three — the trial by Pontius Pilate, Jesus’s crucifixion and death, and his burial, concluding with John 19:42. Texts taken directly from the Gospel of John are set in recitative style for soloists representing Jesus, Pilate, and the Evangelist (John), while arias and chorales, set to contemporary poetry and sung by an SATB chorus and its members, offer reflections on the Gospel and moralizing lessons for the congregation. Bach’s setting calls for a small string ensemble, flute, oboe, and continuo, along with some older instruments such as viola da gamba. Apollo’s Fire, the Cleveland Baroque Orchestra, supplements this ensemble with a bassoon and a contrabass, with director Jeannette Sorrell alternately conducting and providing organ continuo.

As was the custom, Passion settings were split into two halves so that a sermon could be given in the middle. Part I here, based on John 18:1–27, sets two main scenes — Jesus’s arrest and Peter’s denial — while Part II sets three — the trial by Pontius Pilate, Jesus’s crucifixion and death, and his burial, concluding with John 19:42. Texts taken directly from the Gospel of John are set in recitative style for soloists representing Jesus, Pilate, and the Evangelist (John), while arias and chorales, set to contemporary poetry and sung by an SATB chorus and its members, offer reflections on the Gospel and moralizing lessons for the congregation. Bach’s setting calls for a small string ensemble, flute, oboe, and continuo, along with some older instruments such as viola da gamba. Apollo’s Fire, the Cleveland Baroque Orchestra, supplements this ensemble with a bassoon and a contrabass, with director Jeannette Sorrell alternately conducting and providing organ continuo.

The recording is based on a series of concerts from early 2016 in which the named “characters” performed from memory on an elevated stage in the center of the ensemble and members of the chorus occasionally sang from within the audience. Since some of the effects of this “dramatic presentation” are lost on a recording, Apollo’s Fire has posted video excerpts from the performances that can be seen here. The soloists and the ensemble as a whole perform exquisitely; the soloists are incredibly well suited to their roles, the instrumental ensemble is unified and well balanced, and the chorus is exceptional — the opening scenes in Part I are some of the best choral Bach in my recent memory.

Perhaps due to performing from memory and acting out the roles in concert, a few of the soloistic passages are a little rushed, others overly dramatic. These caveats are quite nit-picky, however, as those scenes posted online work well in concert performance. My biggest issue with the recording is with Sorrell’s arrangement of Part II, which she divides into five scenes instead of Bach’s three; many scholars have pointed to Bach’s treatment of texts, keys, and textures in this section as densely symbolic and symmetrical, which this arrangement thus obscures. That larger qualification aside, the musicality and vivacity of the recording are without question, and as such it is a resounding and most welcome success.

Karen Cook specializes in the music, theory, and notation of the late medieval and early Renaissance periods. She is assistant professor of music at the University of Hartford in Connecticut.