by Jeffrey Baxter

Published October 9, 2023

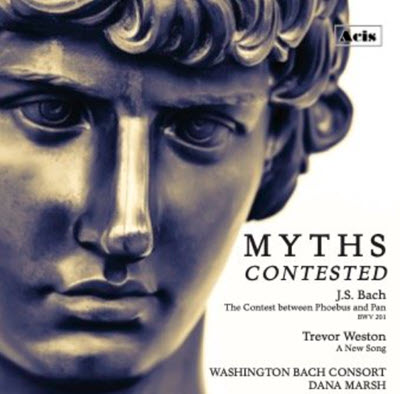

Myths Contested: J.S. Bach’s ‘The Contest between Phoebus and Pan’ (BWV 201) and Trevor Weston’s ‘A New Song’

Washington Bach Consort conducted by Dana Marsh, with soprano Sherezade Panthaki, alto Sarah Davis Issaelkhoury, tenors Patrick Kilbride and Jacob Perry, Jr., and bass-baritones Ian Pomerantz and Paul Max Tipton. Acis APL53752

Myths Contested, the Washington Bach Consort’s first recording in over a decade, presents an interesting pairing of one of Bach’s secular cantatas and a newly commissioned choral work by American composer Trevor Weston (born 1967). The project is described by the consort’s artistic director, Dana Marsh, as an exploration of “enduring ideals both of and about art — as well as notions of aesthetic value, culture, and representation.”

Describing Weston’s evocative A New Song, Marsh explains his approach:

“The text of A New Song responds to an essential theme in the competition found in the myth of the Bach cantata [BWV 201]…Can we evaluate new music without thinking about the old?…post-#MeToo and Black Lives Matter, can we truly evaluate our music history without including music ignored in the past? For many years, our understanding of early music has also been insufficient. The queries surrounding the value of old and new music in A New Song are appropriately represented in new music performed on period instruments.”

Weston’s 20-minute cantata, in eight movements, is scored for a solo vocal trio (soprano, alto, tenor), chorus (here 24 voices), and an orchestra similar to BWV 201’s instrumentation. The composer writes:

“A New Song is a discussion of the differing societal expectations we have for new art…It always struck me that new innovative approaches to music lived in both contemporary music and early music ensembles [and]…that many of the most important innovative composers of the early twentieth century were champions of early music. My cantata ponders these ideas and also addresses a current important trend: performing music by forgotten or ignored composers from the past. A New Song aspires to be entertaining and engaging like a Bach cantata. I did not want to write a new Bach cantata, but…a piece that promotes thought through various musical movements using period instruments.”

When a composer writes their own text it can often be a red flag. But Weston speaks, as conductor Marsh puts it, “in a voice that is both deeply contemplative and sanguine [and] equally direct in its delivery, avoiding specific dialogue exchanges, arguments, and satire.”

The work’s opening movement, “Listen (‘We want to hear luminous sounds’),” includes a chorus in large blocks of homophonic sonorities, couched in a harmonic language that recalls both Barber and Hindemith, but with an undulating orchestral accompaniment that recalls Bach in its florid gestures of flutes and Baroque trumpets.

A solo trio ensues in the second movement, “Time (‘What we feel now reigns’).” The three solo voices, accompanied by quiet strings and portative organ, move in identical motion in a beautifully crafted neo-Medieval style (similar to the sounds beautifully mastered in the Kaija Saariaho’s Troubador-inspired opera L’amour de loin). Soprano Sherezade Panthaki — with her spot-on intonation and clear tone — shines here and throughout the whole work, as so much is set in treble-dominated sections.

In the third movement, “Now seems old,” the gesture of a minuet is conjured, with the chorus positing that “the new song will reimagine the old made with murmurs of the past.” It asks repeatedly: “What is the new song?” The three soloists reply individually, with “A new song speaks for me… for us. Messages from before inform our future thoughts now.” (It is a quaint and beautiful expression, polar opposite to the bold “new song” at the center of Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms: “et immisit in os meum canticum novum”).

The fourth movement, “My song,” may be Weston’s most powerful text, set as a recitative and aria. The first two lines are given as a weighty accompanied recitative for mezzo and strings. The soloist mournfully sings “Wait! My song was ignored. My story erased and told by others.” The next quatrain is cast as a lilting, sad dance in ¾ time, accompanied by flutes and strings, and include the words, “My melody will sing like a mourning dove. Singing my song tells my story.”

In the one-minute fifth movement, “Every story speaks for us,” soprano Panthaki sings lyrically of the past (accompanied by a sarabande-type rhythmic gesture). She continues in soaring, broad legato lines, “Remembering what we left behind expands our view of the new… All who feel can touch us with their meaningful chord,” resolving outward and landing beautifully on an unexpected “chord.”

The Sixth Movement’s “Emotion moves me” propels Jacob Perry, Jr.’s solo tenor forward in the running gesture of constant string motion, recalling a Baroque courante-like dance gesture.

The final two choral movements are the most Bach-like. They include a homophonic chorale, “Music records our days,” and a festive setting of the text, “Hear Life, sing joy,” which bears a distant echo of many a Bach chorale-prelude finale in his cantatas, like the final chorus of Parts II, IV, and VI of the Weihnachts-Oratorium.

While Weston employs some clever rhythmic activity and contrapuntal technique in the orchestra, he reserves the choral sections for an almost exclusive homophonic treatment. While this is certainly appropriate for the opening movement and the penultimate chorale, one wishes he had given even more independence to the individual vocal lines, especially in the finale.

In all, this is a piece that deserves a place in many a concert setting — and not just alongside a Bach cantata performed with period instruments. Its substance and technique would easily translate to modern instruments and could shed light on many of the regularly programmed works heard on the mainstream classical stage. Thanks go to the Washington Bach Consort for bringing this stirring new song to life.

Bach’s Sense of Humor

In contrast to Weston’s evocative A New Song is the intentionally learned humor of Picander’s remix of Ovid’s Metamorphoses in Bach’s drama per musica.

This cantata comes from the repertoire of Bach’s chamber music activity in Leipzig with the Collegium Musicum, a concert-enterprise founded by Telemann and formed of university-student musicians as well as amateurs and professionals. In Bach’s time, the performances took place regularly at the Zimmermann Coffee Haus and included – around 1735 – the Coffee Cantata, BWV 211. A little earlier, in 1729, came Bach’s “aesthetic credo” (as described by Christoph Wolff), in the form of “Der Streit zwischen Phoebus und Pan,” BWV 201.

Music (specifically musical composition and execution) is the vehicle used to depict the aspect of duality in Greek mythology. Picander and Bach provide their own text and music for their version of Ovid’s “Ears of a Donkey,” a tale of a musical/artistic song-contest depicting Apollo’s (aka Phoebus) erudition and heavenly skill and Pan’s earthy approach. From an attending panel of “witnesses,” two judges are appointed (Tmolus for Phoebus, and Midas for Pan).

For many years the cantata was seen as Bach’s reaction to the stinging criticism of his art by composer and music critic Johann Adolph Scheibe, but that dispute did not begin until 1737. Evidence, however, of BWV 201’s likely revival as late as 1749 might lend some credence to this view, but it was certainly not just Scheibe’s barbs that Bach encountered in his artistic life. He always had the greater talent and luckily — in this case — a sense of humor.

The short cantata is elaborately scored (intentionally so?) for six solo voices (SATTBB) of named characters and a “festive” orchestra of trumpets, timpani, (transverse) flutes, oboes (including oboe d’amore), strings and continuo. The work is comprised of six da capo arias (each framed by recitatives) and an opening and closing chorus.

A note here by Marsh lets us know that, in the opening and closing choruses, he uses two supporting ripieno voices (a soprano and an alto), as well as an extra first and second violin, as per Bach’s practice to fill out the sound. It mostly works, but a better balance really cries out for a fuller choral sound, with the six soloists taking each contrasting B-section.

Phoebus’s expansive aria, “Mit Verlangen,” with double obbligato instruments, here beautifully played, is sensitively sung by baritone Paul Max Tipton. However this version of Bach’s indicated Largo could be a click or two faster (the movement clocks in at 9:10). The challenge is of course fitting all of Bach’s elaborate melodic and accompanimental filagree into a manageable tempo that does not end up Adagio.

Pan’s plodding, earthy song, “Zu Tanze,” with its unison string accompaniment above the basso continuo, is dashed off with aplomb by baritone Ian Pomeranz, including all the ridiculously repeated syllables of a heart’s fluttering, at “wackelt” (indicated by Bach to be sung as “wack-ack-ack-ack ack” and said to be heard by some as a scatological joke, with the “k” sounding like the first consonant of a very different word in German slang).

Tmolus, the mountain god and Phoebus’s arbiter in this contest, sings his praises in the aria, “Phoebus deine Melodei,” joined by an affective oboe d’amore obbligato. While Phoebus’s heavily scored aria of divine length was designed to win, it is the introspection and eloquence here delivered by tenor Jacob Perry, Jr., a standout in this cantata’s performance, that for me takes the prize.

In a comic stroke of genius, Bach sets Midas’ song of praise, “Pan ist Meister,” in a rollicking stride that gives us actual donkey brays in downward leaps of an octave and a half in the accompanying violin line, at the text, “nach meinen beiden Ohren” (“according to my two ears”). He even writes for Midas to bray similarly at the end of the A section (and its da capo) by singing a downward leap of a 7th (from C-sharp to D), unfortunately omitted by the singer here, Patrick Kilbride, who instead resolves the melody up stepwise, missing the joke.

Mercury, in an alto aria accompanied by two virtuoso flutes, sings how puffed-up pride and inability will get the fools cap and, in the B-section, describes in quick downward octave leaps on “schaden” and “Schanden” (“harm” and “shame”) how such foolhardiness at the helm can sink a ship. Pan is ultimately declared the loser, and his supporter, Midas, is summarily dismissed with a “sashay away” by Phoebus and the rest of the judge’s panel. And in the only accompagnato recitative, Momus offers both consolation to Midas and resignation to the fact that there are more fools than wise.

Jeffrey Baxter is a retired Choral Administrator of the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, where he managed and sang in its all-volunteer chorus and was an assistant to Robert Shaw in his final years. He holds a doctorate in choral music from The College-Conservatory of Music of the University of Cincinnati and has written for BACH – The Journal of the Riemenschneider Bach Institute, The Choral Journal, and ArtsATL.