by

Published May 6, 2019

J.S. Bach: Cantatas For Luther, BWV 76, 79, and 80

Hélène Brunet, Michael Taylor, Philippe Gagné, Jesse Blumberg; Montréal Baroque (Eric Milnes, conductor)

ATMA Classique ACD22407

By Andrew J. Sammut

Lutheranism was essential to Bach’s personal and professional life, so religious music honoring the origins of the faith likely had a special significance for him. For the eighth release in ATMA Classique’s Bach sacred cantata series, Montréal Baroque under Eric Milnes’ direction highlights works celebrating the day Martin Luther nailed his Ninety-Five Theses to All Saints’ Church.

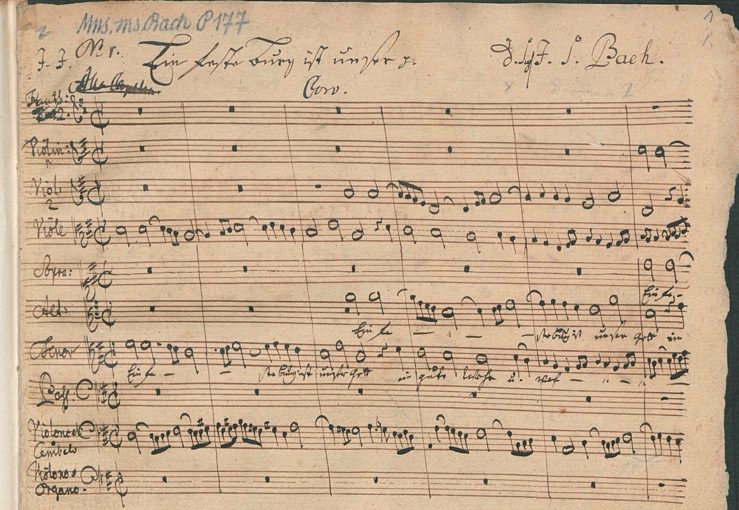

These Reformation Day cantatas were all composed or completed within the early years of Bach’s Leipzig period. “Die Himmel erzählen die Ehre Gottes,” BWV 76, and “Gott der Herr ist Sonn und Schild,” BWV 79, both use words by unknown poets, while Bach’s frequent librettist Salomon Franck wrote “Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott,” BWV 80. Like many of Bach’s cantatas, these three combine original texts with Lutheran chorale hymns into settings for chorus, vocal soloists, and recitatives, with rich instrumentation.

These Reformation Day cantatas were all composed or completed within the early years of Bach’s Leipzig period. “Die Himmel erzählen die Ehre Gottes,” BWV 76, and “Gott der Herr ist Sonn und Schild,” BWV 79, both use words by unknown poets, while Bach’s frequent librettist Salomon Franck wrote “Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott,” BWV 80. Like many of Bach’s cantatas, these three combine original texts with Lutheran chorale hymns into settings for chorus, vocal soloists, and recitatives, with rich instrumentation.

The texts’ imagery and metaphors clearly inspired Bach. A repeating arioso for the closing lines of the first alto recitative of BWV 76 softly reinforces the speaker’s prayers. The faithful’s voices extolling God’s words in BWV 79’s penultimate movement are conveyed through soprano and bass in a strong yet lyrical — and mostly non-contrapuntal — union. That cantata opens with a martial instrumental fugue ingeniously unwinding its thematic material before the voices declare God’s strength.

Montréal Baroque and four confident vocalists prioritize solemnity over extroverted spirituality. Soprano Hélène Brunet sings with calm conviction and resolute delivery. She is refreshingly restrained in BWV 80’s solo aria, avoiding the tendency to exaggerate its wide intervals. Countertenor Michael Taylor brings a cool androgyny and understatement to his solos that is well-suited to the otherworldly side of this music. His alto aria in BWV 79 hails God with a maturity missing in more overtly youthful performances.

These readings are far from lacking in energy. Baritone Jesse Blumberg laces into the “idolatrous band” of BWV 76’s bass aria without bluster here or throughout the disc. Clear-toned tenor Philippe Gagné spits out “hate” in increasingly dissonant lines in his aria in BWV 76 before turning sweet for the second section. The affects remain natural and compelling on their own terms, yet some listeners might make comparisons with performances featuring bolder expression and bigger choruses.

The four soloists sing together for the choral movements. This one voice per part interpretation adds clarity without seeming slight, even if BWV 79’s fugue is more like a ceremonial procession than a regiment. The haunting chorale finishing both parts of BWV 76 has more than enough weight to convey this uncanny communion with God. When a four-person ripieno choir joins for the opening of BWV 76, it comes off like an interesting contrast rather than a “fuller” sound, per se.

The orchestra is likewise balanced and sympathetic. The eight-person string section plays with a breadth that belies its size: lushly seconding praise of God in BWV 76’s tenor recitative or, along with oboes, racing in imitation of devils around the resolute voices of BWV 80’s central chorus. Bright, clear brass add majesty, for example alongside the chorus in BWV 79’s central chorale (though the horns and trumpets are sometimes oddly forward, such as the pedals in BWV 76’s bass aria).

Several obbligatos demonstrate Bach’s signature contrapuntal craftsmanship with voice and oboe as well as this ensemble’s unity of concept and texture. Warm, transparent instrumental dialogues also appear, such as violin and viola da gamba in BWV 76’s soprano aria or the instrumental sinfonia for oboe d’amore and gamba opening the second part of the same cantata. Oboe da caccia and violin form a double trio sonata alongside the alto and tenor for BWV 80’s last aria, further highlighting the richness of Bach’s writing and this group’s sound.

Milnes’ modest tempos and subtle direction maintain musical as well as narrative cohesion. He conjures powerful but elegant massed effects, such as BWV 79’s closing chorale, without overdoing it as well as utterly lucid moments like BWV 80’s second movement, where Blumberg pours out the aria while Brunet and oboe chant the chorale in airtight unison over an insistent string ritornello. “Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott” (A mighty fortress is our God), a hymn virtually synonymous with Lutheranism, opens BWV 80 and exemplifies this album’s reverent yet uniquely moving aesthetic.

Andrew J. Sammut has written about early music and hot jazz for All About Jazz, Boston Classical Review, The Boston Musical Intelligencer, Early Music America and the IAJRC Journal as well as his own blog. He lives in Cambridge, MA.