by

Published October 13, 2017

Polish Style in the Music of Johann Sebastian Bach. Szymon Paczkowski.

Rowman & Littlefield, 2017. 418 pages.

By Mary Greer

BOOK REVIEW — The musical and metaphorical role of the polonaise and “the Polish style” more generally in J. S. Bach’s works is explored in the most recent volume of Contextual Bach Studies, edited by Robin A. Leaver. Warsaw-based musicologist Szymon Paczkowski is uniquely qualified to undertake the first comprehensive study of this subject. The author first describes the characteristic rhythmic and structural features of the dance and the affects associated with it, and traces how it came to be introduced into Germany.

Paczkowski credits German musicologist Ortrun Landmann as the first to identify the metaphorical role of the polonaise in Baroque music. Upon Friedrich August I’s accession to the Polish throne as August II in 1697, Dresden became a royal residence and an important locus for the reception of Polish dances in Germany. In Saxony, the polonaise, a majestic, processional dance that was a fixture in Dresden court ceremonies, came to be associated with the Polish crown, then with royal power and majesty in general, and subsequently with the King of Heaven.

Paczkowski credits German musicologist Ortrun Landmann as the first to identify the metaphorical role of the polonaise in Baroque music. Upon Friedrich August I’s accession to the Polish throne as August II in 1697, Dresden became a royal residence and an important locus for the reception of Polish dances in Germany. In Saxony, the polonaise, a majestic, processional dance that was a fixture in Dresden court ceremonies, came to be associated with the Polish crown, then with royal power and majesty in general, and subsequently with the King of Heaven.

Paczkowski then situates the polonaise in the cultural, sociological, and historical landscape of Bach’s time. While the polonaise does not feature prominently in Bach’s instrumental works, elements of the dance appear in a sizable number of his sacred and secular vocal movements. In a series of case studies, Paczkowski shows that Bach was prompted to incorporate the polonaise into a work not solely for musical considerations but, above all, on account of a nexus of literary, cultural, historical, sociological, and theological associations.

He is particularly effective in elucidating aspects of works with a demonstrable connection to the royal court in Dresden. He reminds us that, within five months of submitting his petition to be named court composer to the king of Poland and elector of Saxony in late July 1733, Bach composed four drammi per musica celebrating notable events in the life of August III and members of his family. Though other scholars have noted the presence of a polonaise in most of these movements, by drawing upon the evidence of surviving sources, 18th-century music theorists, historical events, cultural, and sociological phenomena, as well as classical mythology, Paczkowski considerably enriches and amplifies our understanding of these works, several of which were incorporated into the Christmas Oratorio (BWV 248). The connections he draws between the pervasive references to Roman mythology in the libretto of Tönet, ihr Pauken! Erschallet, Trompeten! (BWV 214), composed in honor of Maria Josepha’s birthday on December 8, 1733, and contemporaneous political events, is especially impressive.

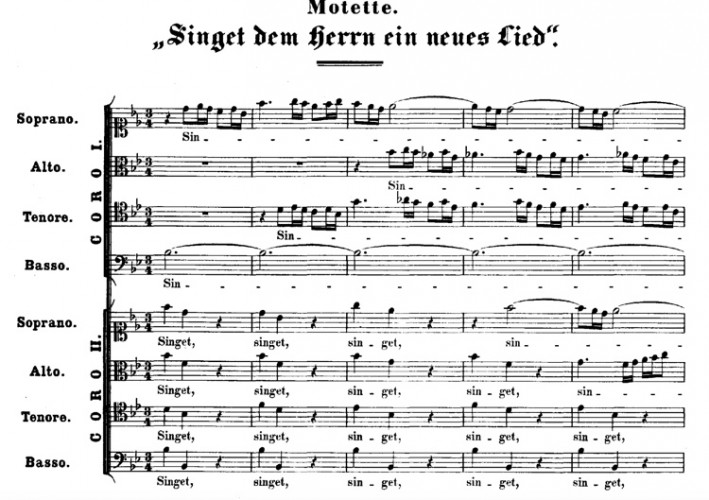

However, at times, Paczkowski’s desire to highlight the importance of the polonaise in Bach’s works undermines his objectivity. A case in point is his discussion of the motet Singet dem Herrn ein neues Lied (BWV 225). In his eagerness to demonstrate that Bach’s use of the polonaise in the opening movement helps corroborate Konrad Ameln’s unproven hypothesis that the motet was first performed on May 12, 1727, on the occasion of the visit to Leipzig of August II, King of Poland and Elector of Saxony, Paczkowski is highly selective in his analysis of Psalm 149:1–3, the basis of the opening movement, and the Lutheran theologians he cites. These verses read:

Sing unto the Lord a new song, And his praise in the congregation of saints!

Let Israel rejoice in him that made him, Let the children of Zion be joyful in their king!

Let them praise his name in the dance…

Paczkowski highlights the words “Könige” (king) and “Reigen” (dance) and cites Johann Olearius’s comment on the psalm, but gives short shrift to the psalmist’s two injunctions to rejoice, and makes no mention of Abraham Calov’s comment on verse 2 in Die heilige Bibel (Wittenberg, 1681, vol. I/2, 871), “that is the first, that the praise shall take place with joy.” Surely this would have been an ideal opportunity to point out that the rhythmic figure of an eighth note followed by two sixteenths was associated with both the polonaise and with what Albert Schweitzer terms “motives of joy” in Bach’s music. While Paczkowski does allude to this in the first chapter, his failure to mention the “joy motive” in this context is puzzling. In Bach’s setting of Psalm 149, inspired by the references to “rejoice,” and “king” and “dance,” he exploited the common language of Schweitzer’s “joy motive” and the characteristic rhythm of the polonaise to create a jubilant musical setting that gave expression to and amalgamated all three of these elements.

Paczkowski makes a persuasive case that Bach consciously incorporated elements of the polonaise into certain of his works for both musical and allegorical reasons and that the dance — and Polish style in general — occupied a significant place in Bach’s lexicon of musical symbols. This carefully researched but highly readable study is an invaluable resource for scholars, performers, and students who seek greater insight into the musical, cultural, political, and sociological milieu in which Bach lived and worked.

Bach specialist Mary Greer is a musicologist and conductor. Her research focuses on Bach’s Calov Bible, St. Matthew Passion, and the Bach family’s connections to Freemasonry. She edited BACH: The Journal of the Riemenschneider Bach Institute from 2013 to 2017.