The show was not supposed to end this way. Nicholas McGegan’s final bow as music director of Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra (PBO) and Chorale promised to be a spectacular leave-taking. The irrepressibly animated conductor had chosen as his swan song a fully staged, historically informed production of Jean-Marie Leclair’s only opera, Scylla et Glaucus, scheduled to be presented in mid-April at Herbst Theatre in San Francisco in a collaboration between PBO and the Center for Baroque Music at Versailles. From there, it would have headed back to the Old World for another round of performances at Versailles, the historic center of the French Baroque.

But the coronavirus pandemic has forced a nearly universal change of tense to future perfect conditional. Among the countless cancellations that have been announced in recent weeks, the Leclair performances would have served as a wonderfully fitting double bar concluding McGegan’s 34-season tenure leading PBO. (Whether the production can be presented later in the year remains to be determined.)

“I decided on the Leclair for my final production because I wanted to do something that really had a story,” McGegan told me during a generously lengthy interview in February — not long before a deadly virus would transform the straightforward future tense, along with our sense of anticipation, into utopian longing.

The idea of staging Scylla et Glaucus, a 1746 tragédie en musique based on the mythic tale of jealousy and revenge from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, was conceived as a kind of counterpart to another relatively recent project McGegan singles out among favorite highlights over his many years with PBO: Jean-Philippe Rameau’s Le Temple de la Gloire, an opera-ballet of nearly the same vintage (1745) that the Bay Area ensemble presented to great acclaim in April 2017.

“Each act of the Rameau has a moral to show what makes a good king,” McGegan said — mostly by way of cautionary tales, as Voltaire’s libretto first presents a pageant of examples who are not fit to enter the Temple of Glory before revealing the model for King Louis XV, the opera’s patron. Scylla et Glaucus, by contrast, is “an opera in the conventional sense, with real drama. It has a plot involving jealous love and ends sadly with the death of one of the characters.”

Dance is highlighted by both Rameau and Leclair. But while Le Temple is “sort of an excuse for a lot of dancing, with a bit of plot,” Leclair integrates the ballet into the story. “And his dance music is amazing,” McGegan said, “because Leclair was a dancer himself, as well as an incredible violinist.”

The creative team McGegan assembled for the Leclair production offered an occasion to reunite with artists he has happily collaborated with over the years — both at PBO and beyond. He enlisted figures who had worked with him during his period with the Handel Festival in Göttingen (which he directed from 1991 to 2011) and who had also come to the Bay Area to stage Le Temple de la Gloire.

Choreographer and director Catherine Turocy first partnered with McGegan as far back as 1985, as part of Pepsico Summerfare’s festival of three Handel operas in Purchase, NY. His assignment was an authentically Baroque Teseo “with flying machines, which I staged as well as conducted.” Along with Peter Sellars’s avant-garde Giulio Cesare and Andrew Porter‘s “middle of the road” staging of Tamerlano, the trilogy encapsulated three viable ways of presenting Handel as the renaissance in staging his operas began to gain a wider audience.

For the Leclair project, Turocy worked on creating a historically informed Baroque staging. (She had herself danced in John Eliot Gardiner’s production of Scylla et Glaucus at Lyons in the mid-1980s.) PBO’s version would have marked its U.S. stage premiere, as far as McGegan is aware. Costumes and lighting were designed by Marie Anne Chiment and Pierre Dupouey, respectively, while McGegan, Turocy, and Dupouey jointly created the set designs.

The prospect of staging Le Temple et le Gloire, which PBO also recorded and released on its in-house label, had been on McGegan’s to-do list for nearly a quarter-century before he was able to realize it three years ago. “It took that long to get the right alignment of funding and planning,” said the conductor, who was eager to bring to life Rameau’s original 1745 version — the manuscript of which was thought to be lost until it was discovered in the collection of the University of California at Berkeley library. Representing a kind of Baroque total artwork in its fusion of elements, PBO’s staging struck San Francisco Chronicle critic Joshua Kosman as akin to “watching a resplendently bedecked giant stirring to life.”

Heading West: Early Years with the PBO

But instrumental music was PBO’s primary focus when McGegan was originally lured out West to the Bay Area in 1985 — “half my life ago, now that I’ve just turned 70 [in January 2020],” he mused. Founded in 1981 and originally led by harpsichordist Laurette Goldberg, the PBO that McGegan initially encountered was “rather like a commune. Every rehearsal resembled a Quaker meeting, where the musicians would let the Spirit move them to find a B-flat. They could rehearse for a week and actually get nothing done. There were lots of babies to feed. A general slightly countercultural type of environment prevailed.”

Many of the musicians in the American music scene, he said, had trained in Europe — especially in Holland, “whether to get out of the Vietnam War or whatever the case was” — and then come back to settle in Boston or the Bay Area, with some pockets in the Midwest as well. “It was in the mid to late 1970s that this started to coalesce. Laurette Goldberg herself was a friend of Gustav Leonhardt and studied under him, so the PBO originally was very Dutch-leaning.”

McGegan was asked to come in and bring some order — “but not like a German conductor. I like to think of myself as a benign tyrant. With me, it was more by negotiation than fiat. But I did have some definite views.”

One of these, which shaped the PBO’s course, was to create a liaison between the orchestra and one of the choirs at UC Berkeley led by the conductor and musicologist Philip Brett, a member of the Berkeley faculty. “So we bonded with UC Berkeley in terms of what they were doing musically and used the Berkeley Chamber Chorus until Philip moved to Riverside in Southern California in the early 1990s. Then we decided to found our own choir and became the PBO and Chorale.”

Even before being named music director, McGegan’s first engagements with PBO foreshadowed the intense focus on Handel that would become a signature of his tenure. In 1984, he guest-conducted the ensemble in a production of Apollo e Dafne that was recorded after making a little tour of Oregon. Their earliest recording together using the Berkeley choir was of Handel’s Susanna (with mezzo-soprano Lorraine Hunt Lieberson), which was nominated for a Grammy Award as Best Choral Performance in 1990.

Under McGegan’s leadership, PBO became one of the most-recorded international period-music ensembles, tallying a rich discography of some 40 recordings. McGegan’s own recorded output over the past five decades numbers more than 100 releases, over half of which are of Handel (almost 20 of the operas and 12 oratorios). Along with this legacy, his tours with the PBO helped establish the ensemble’s international status as a leader and tastemaker for North America’s early-music scene.

Characteristically, McGegan downplays his own significance in building this clout. “Every record company tends to put you in a pigeonhole. OK, you’re the Handel guy. Bill Christie will do French music. Which of course was not in any way uncongenial.” Performing Handel with PBO, he points out, had “a lot of advantages” in the ensemble’s early days. “We had a choir and orchestra we could use to perform things in English. Our singers were well-versed in singing Handel but would not have been so well-versed in, say, Rameau at that date. And English is very approachable for an audience here.”

The majority of the PBO, according to McGegan, are in their 50s and early 60s. “That means we have had a very stable personnel, which has enabled us to have a house style. That’s very different from a lot of the European orchestras, where the same people might play in three different ensembles.” How does he characterize this house style? “We are not as highly caffeinated as some of the Italian groups, for example, nor as extreme as some other ensembles. Our strings are particularly beautiful because a lot of these musicians have been making music with the same people since the last century.”

At the same time, there has been an infusion of young blood from the program PBO runs with Juilliard — where McGegan also makes regular appearances — whereby one or two students come to Berkeley to play almost every set.

A Conductor Cuts His Teeth

Born in 1950 in a small town north of London in the home counties, McGegan came of age when those drawn to early music “had to read the original treatises for ourselves because we didn’t have a teacher for original instruments.” Already in his 20s, he was collaborating as a flutist and harpsichord continuo player with Christopher Hogwood, John Eliot Gardiner, Roger Norrington, and Trevor Pinnock. It was a whirlwind scene of continual discovery and unexpected opportunities. “One day, Pinnock caught his hand in a train door and I had to play a concert of the Four Seasons on a single day’s notice.”

At the end of McGegan’s influential years amid the British early-music scene, it was Pinnock who steered his young protégé toward America, recommending him to teach for a semester at Washington University in St. Louis in 1979. McGegan stayed until 1985, when he took up the offer from PBO.

“Washington University had an early-music performance practice program with very good students. I was also an artist in residence, so we had a grand time putting on a Handel opera and doing all kinds of wacko stuff. Over at Opera Theater of St. Louis, I did some Gilbert & Sullivan as well.” He maintains a close bond with the city and returns regularly to conduct the St. Louis Symphony.

McGegan fondly recalls being called out to Long Beach in these years to work on avant-garde stagings with the Alden brothers, Christopher and David. “That’s how I cut my operatic teeth: through more experimental things rather than the more normal route of going through the opera house and learning the standard repertoire. I was doing Poppea and Ulisse and all kinds of fun stuff.”

This delighted embrace of such collaborations anticipated the marriage between historically informed performance practice and avant-garde staging (particularly of Handel) that in the decades since has become a regular feature of the early-music world. It also points to the flexibility and freedom from a dogmatic mindset that make McGegan’s style of making music so consistently fresh and full of joy.

Proud Moments

It may be a bit hard from today’s vantage point to recall just how rigid the early-music scene could be in the years even when the mainstream was already absorbing its influence. McGegan recalls that around 1988, he began following European trends of branching out in the repertoire beyond what was considered by his audience the “domain” for early music. “That’s when we first started to do Mozart and Haydn. Rather tentatively at first, because, believe it or not, we got a bit of backlash from our audience. Some wanted wall-to-wall Bach and Telemann and would complain that they could go to San Francisco Symphony if they wanted to hear Mozart.”

McGegan is especially proud of where extending the boundaries eventually led. In terms of the canon, PBO pushed this trend to early Brahms. But it also enthusiastically embarked on a pattern of commissioning pieces for period instruments, starting with Jake Heggie’s To Hell and Back (2006), a retelling of the Persephone myth for soprano, Broadway soprano, and period-instrument orchestra. PBO and McGegan have since commissioned works from Sally Beamish, Mason Bates, Matthew Aucoin, and Caroline Shaw. Premiered at the beginning of the 2019-2020 season, Shaw’s “shimmery and often heart-tugging oratorio” (Kosman) The Listeners sets to music ideas suggested by Carl Sagan’s Golden Record for NASA.

“I hate to have people coming to our concerts because they assume it will be ‘the safe option’ and they know they’re not going to be scared and challenged,” said McGegan. “I think music should be challenging. All the music we play was new once. It’s so great to have the composer actually with you to explain, ‘Well, no, that wasn’t quite the effect we wanted, let’s try this’ — as opposed to getting a fancy collected edition off the library shelves and just playing it.”

Other favorite achievements? McGegan immediately refers to PBO’s ongoing collaborations with the choreographer Mark Morris, impishly adding that these have been “about as much fun as you can have legally and in public. It’s just a romp to work with Mark.” Their signature piece together is Handel’s L’Allegro, il Penseroso ed il Moderato (originally created by Morris in 1988), which they have revived many times — and which McGegan has done with several other orchestras as well.

McGegan singles out other collaborations featuring Morris’s choreography: Rameau’s Platée (“one of the funniest things I’ve ever been involved with, which started at Covent Garden”); Handel’s Acis and Galatea in the arrangement by Mozart; and Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas. “The Dido was particularly stimulating,” McGegan added. “It’s a bumpy ride sometimes with Mark, but it’s always great.”

The word fun comes up frequently in conversation with McGegan. But its implications go far beyond an impulsive pleasure in the moment. This is a philosophy of making music that PBO has inscribed into its mission statement as follows: “Historically informed performance means more than playing music in the style in which it was written; it also means performing music with a passion, joy, and vitality that provide a meaningful contemporary artistic experience for today’s audience.”

McGegan’s insatiable curiosity and appetite for this kind of enjoyment is delightfully illustrated in the blog section of his website, Roving & Recipes, a kind of travelogue that records his impressions of tour stops along with favorite recipes the gourmand collects along the way. (A trip to Wrocław following a concert in Szeczin is accompanied by evocative descriptions and photographs and a recipe for Polish apple pie.)

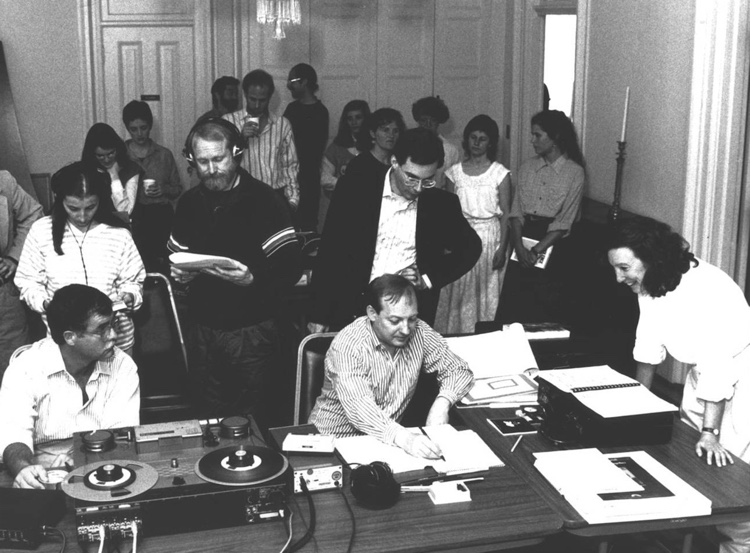

While McGegan’s years as PBO’s music director have now reached their end, he is emphatically not retiring. He will keep his residence in Berkeley with his husband, David Bowles (PBO’s recording engineer). “I just turned 70 and would like to think there may be eight or nine years or maybe even a decade of doing stuff left. So I’m going to spend that making music rather than organizing it.”

Being freed of the extramusical demands of a directorship means the opportunity “to do things that I didn’t have time for in the past — especially to do more opera. I’d love to do the Mozart operas again. And I enjoy traveling and being challenged.”

McGegan ends with a bit of advice for his successor: “It’s important for any conductor to spend time with the musicians rather than up in the clouds with the board. Spend as much time as you can with them. They have a lore of knowledge that goes back a long way.”

Thomas May is a freelance writer, critic, educator, and translator whose work has been published internationally. The English-language editor for Lucerne Festival, he also writes for such publications as The New York Times and Musical America.