by

Published August 19, 2019

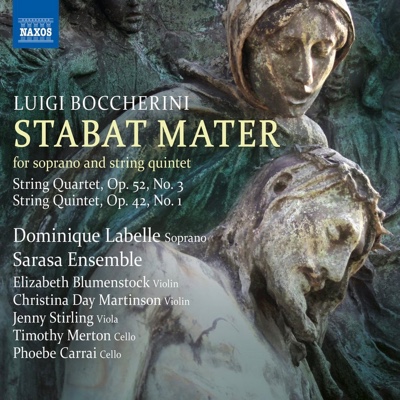

Luigi Boccherini: Stabat Mater

Dominique Labelle, soprano; Sarasa Ensemble (Elizabeth Blumenstock, Christina Day Martinson, violins; Jenny Stirling, viola; Timothy Merton, Phoebe Carrai, cellos)

Naxos 8.573958

By Benjamin Dunham

I admit to having a split personality in my taste for sopranos. In my Mr. Hyde guise, I confess to a weakness for Renata Tebaldi, Birgit Nilsson, Leontyne Price, Eileen Farrell, and Jessye Norman, voices that can overwhelm me with their power and vibrancy. As Dr. Jekyll, I tend to favor Elly Ameling, Benita Valente, Jean Hakes, Dorothy Maynor, and Maggie Teyte, voices that charm with their intelligence and warmth. To that last category you can add Dominique Labelle, and for an example of her vocal radiance you can take pleasure in her recording of Luigi Boccherini’s Stabat Mater for soprano and string quintet (G. 532) with Sarasa Ensemble, recently released on the Naxos label.

Sarasa Ensemble is a Boston collective with both a wide-ranging artistic scope and an admirable social purpose. Under the leadership of co-directors and cellists Jennifer Morsches and Timothy Merton, they have contributed importantly to the New England music scene for more than two decades and toured Ireland, India, and Cuba. In 2007, the group won Early Music America’s Outstanding Achievement Award for their work with incarcerated teens.

Sarasa Ensemble is a Boston collective with both a wide-ranging artistic scope and an admirable social purpose. Under the leadership of co-directors and cellists Jennifer Morsches and Timothy Merton, they have contributed importantly to the New England music scene for more than two decades and toured Ireland, India, and Cuba. In 2007, the group won Early Music America’s Outstanding Achievement Award for their work with incarcerated teens.

Their latest CD brackets Boccherini’s religious work with two pieces of chamber music for strings, a quartet, Op.52, No. 3 (G. 234), in G major, and a quintet, Op. 42, No. 1 (G. 348), in F minor.

While it is possible to discover apt word-setting in Boccherini’s setting of the Stabat Mater, the stronger characteristic is the subsuming of everything into a flowing aural panorama, one the instruments do little to disturb. For example, you can certainly imagine the sadness in the vocal line against the anxious instrumental opening of “Quae moerebat et dolebat,” but in “Pro peccatis suae gentis” the scourging of Christ is so closely fitted into a gracious melodic framework that the underlying torment comes through only in the relative intensity of Labelle’s coloratura. The work closes with the heartfelt “Quando corpus morietur,” contemplating the end of life, and a quiet, hopeful “Amen.”

In the string works, the talented performers emerge only sporadically from a somewhat distant recording perspective. Listening to the string quartet that opens the program, you can appreciate the validity of contemporary praise of Boccherini’s originality and melodiousness while fully understanding how his music could have been overlooked in the heated atmosphere of the 19th century and even into the present.

In the two-cello quintet, one of 113 Boccherini wrote that have the same instrumentation as Schubert’s C-major quintet, you have to wonder if Schubert was aware of Boccherini’s works for this combination, and if so, how he was able to project the drama of his powerful composition from the rather modest goals of Boccherini’s conception. In the third movement, there is a lovely solo moment for cellist Merton, a part the composer presumably wrote for himself.

As a worthy document of Boccherini’s chamber style, this CD is of value for its all-embracing charm, but the more urgent appeal will be to fans of the iridescent voice of Labelle.

Formerly editor of American Recorder and Early Music America magazines, Benjamin Dunham has reviewed for Musical America, The Washington Post, and Gatehouse Media.