by Erica Buurman

Published July 5, 2021

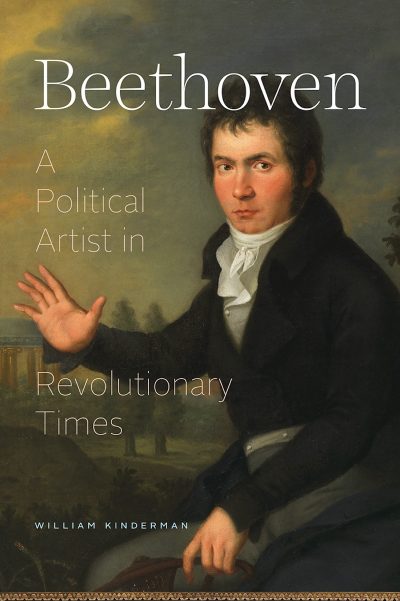

Beethoven: A Political Artist in Revolutionary Times. William Kinderman. University of Chicago Press, 2020. 256 pages.

There is no shortage of anecdotes about Beethoven’s enthusiasm for the ideals of the French Revolution and abhorrence of repressive regimes. From his tearing up of the dedication page to the Eroica Symphony on learning of Napoleon’s self-coronation in 1804 to his refusal to remove his hat for royalty while strolling with Goethe, Beethoven’s most celebrated political actions indicate strongly-held convictions and a spirit of resistance — all of which found obvious expression in his only completed opera.

Beethoven’s politics have come under renewed scrutiny in recent scholarship. Some musicologists have been more inclined to give serious attention to the full range of political sentiments in his music rather than sidelining those that support rather than resist the status quo — particularly the bombastic, propagandistic pieces of the Congress of Vienna period. William Kinderman’s new book, Beethoven: A Political Artist in Revolutionary Times, however, resists any such revisionist approach. Instead, Kinderman focuses on Beethoven’s lifelong belief in freedom and progress as universal ideals that found expression in his music in all periods of his life in ways that continue to resonate to the present day.

Beethoven’s politics have come under renewed scrutiny in recent scholarship. Some musicologists have been more inclined to give serious attention to the full range of political sentiments in his music rather than sidelining those that support rather than resist the status quo — particularly the bombastic, propagandistic pieces of the Congress of Vienna period. William Kinderman’s new book, Beethoven: A Political Artist in Revolutionary Times, however, resists any such revisionist approach. Instead, Kinderman focuses on Beethoven’s lifelong belief in freedom and progress as universal ideals that found expression in his music in all periods of his life in ways that continue to resonate to the present day.

Beethoven was clearly drawn to dramatic works with themes of heroism and political progress, and unsurprisingly Fidelio and Egmont loom large in this study. Kinderman provides a close analytical reading of the political themes in these works but also contextualizes them within Beethoven’s engagement with political subjects throughout his life, beginning with his formative years in Bonn. Schiller’s Don Carlos (1787), for instance, was read enthusiastically by the young Beethoven and his friends, and Kinderman also views aspects of Schiller’s aesthetic philosophy as being a key influence on the composer. He connects the Pathétique Sonata, Op. 13, for instance, with Schiller’s treatise Über das Pathetische, which argues that tragic art embeds moral resistance and utopian striving rather than merely depicting a state of melancholy.

Kinderman’s book brings into sharp focus the turbulent politics Beethoven experienced within his lifetime, from his time in Bonn in a period that encompassed the start of the Revolutionary Wars to the reactionary politics of Habsburg Vienna. Much has already been written about the progressive politics in Beethoven’s Bonn, whose university and Lesegesellschaft (reading society) cultivated Enlightenment literature and ideas. Beethoven had connections to the Lesegesellschaft through his teacher Christian Gottlob Neefe and his patron Count Waldstein, though Kinderman draws attention to a less familiar figure within Beethoven biography: Eulogius Schneider (1756–1794).

Schneider, who took up a position at the university in 1789 (the same year Beethoven enrolled as a lay student), was an outspoken supporter of the French Revolution and was critical of Catholic ritual and orthodoxy. His revolutionary politics led to his dismissal from the university in 1791, and he later settled in Strasbourg, where he led a radical overthrow of the mayor. During the Reign of Terror, he sent at least 30 people to the guillotine but was himself arrested and guillotined under the Robespierre regime in 1794. Through his focus on Schneider, Kinderman highlights the radical views to which Beethoven was exposed in Bonn and demonstrates that lives and careers could be on a knife-edge during those turbulent post-Revolutionary years.

In the many detailed and insightful analyses woven throughout the book, Kinderman offers readings of various Beethoven works in political terms, from the “Flohlied” from Goethe’s Faust, Op. 75, No. 3, to various instrumental works. Some of the most compelling political readings relate to Beethoven’s stormiest minor-key works (as might be expected), including the “Tempest” Sonata, Op. 31, No. 2, the “Appassionata” Sonata, Op. 57, and the Piano Sonata, Op. 111. (The audio examples that accompany the book include Kinderman’s own recordings of some of this music). Observing that Beethoven frequently composed a keyboard work in connection with a large-scale dramatic piece, he also makes a persuasive case for considering the “Appassionata” and “Waldstein” sonatas as belonging to the same political world as the broadly contemporaneous Fidelio in its original version.

In addressing the handful of works in Beethoven’s output that express patriotic or populist sentiments, Kinderman provides strong grounds for considering them to be composed for economic or pragmatic reasons rather than as deeply-felt political expressions. Some engagement with the alternative interpretations of these works that have recently been put forward by other scholars, which Kinderman alludes to in the opening chapter but does not discuss directly, would nevertheless be welcome. Overall, however, the book makes a valuable contribution to our understanding of Beethoven as a politically engaged artist and reveals politics to be a vital context for some of his most important works.

Erica Buurman is director of the Ira F. Brilliant Center for Beethoven Studies and assistant professor at San José State University.