by Mark Kroll

Published January 18, 2021

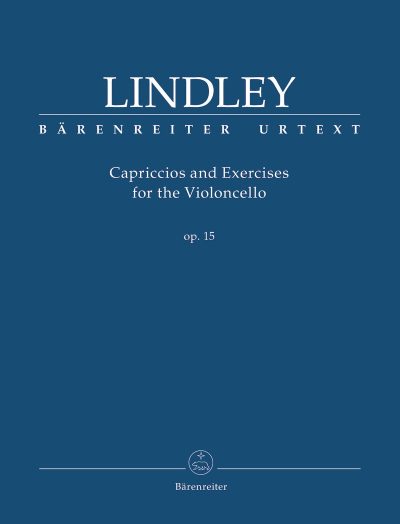

Robert Lindley, Capriccios and Exercises for the Violoncello, Op. 15. Valerie Walden, editor. Kassel: Bärenreiter Verlag, 2019, BA 10936. 30 pages.

Robert Lindley (1776-1855) is one of those important figures in music history that you’ve probably never heard of. Yet he can justly be credited with founding the English School of cello playing.

Born in Rotheram, Yorkshire, England, he first studied with his father, achieved sufficient skill to perform concertos in public two years later, and finished his training with the leading English cello teacher of the time, James Cervetto (1748-1837), himself the son of a noted cellist, G.B. Cervetto (1680-1783). Lindley went on to have a long and illustrious career as a performer and teacher. The press never failed to mention his “absolutely astonishing” execution and “rich, powerful, and sweet” sound, and remarked: “England boasts of having given birth to, and at this moment of possessing, the finest performer on the violoncello in Europe.”

Indeed, Lindley seems to have been everywhere in London’s musical scene for more than 50 years. He held the first chair position in all of London’s major orchestras and performed as a soloist and chamber musician at every high-profile benefit concert until his retirement in 1851. I discovered this firsthand when I was writing my biographies of Johann Nepomuk Hummel and Ignaz Moscheles. Whenever my research led me to England, I kept running into the name Lindley in almost every orchestral and chamber program.

Indeed, Lindley seems to have been everywhere in London’s musical scene for more than 50 years. He held the first chair position in all of London’s major orchestras and performed as a soloist and chamber musician at every high-profile benefit concert until his retirement in 1851. I discovered this firsthand when I was writing my biographies of Johann Nepomuk Hummel and Ignaz Moscheles. Whenever my research led me to England, I kept running into the name Lindley in almost every orchestral and chamber program.

A major part of Lindley’s career was devoted to teaching. Appointed the first cello teacher in the newly established Royal Academy of Music in 1822, his pedagogical skills even received praise from non-English sources, such as F.J. Fétis, who in 1829 wrote about Lindley’s “great reputation…he sings upon his instrument, he produces a fine tone, [and] has formed good pupils in the academy.”

An indication of his dedication to teaching are the duets and capriccios he composed for his students and the cello-playing public. The most important, the set of Capriccios and Exercises for the Violoncello, Op. 15, has recently been published and carefully edited by the noted scholar of cello history, Valerie Walden, and brought out by Bärenreiter in its trademark elegant and eminently readable format. Not only does it fill an important gap in our knowledge of the history of cello playing, but it also will be of great use to teachers and students of the instrument.

Walden’s edition is a model of clarity and thoroughness, and dispatches some of the mysteries and eccentricities of 19th-century cello notation that sometimes plague today’s cellists. These include Lindley’s use of the French style, in which notes in the middle register of the instrument are notated in treble clef but are to be played one octave lower than written, while upper-register notes are written at pitch; and the use of an “X” to designate the thumb. Walden adds copious fingering suggestions, all of which are clearly distinguished from Lindley’s own.

Her concise but informative introduction is equally valuable. For example, we learn that many 18th- and 19th-century violinists composed etude caprices but that the genre for cello was relatively new in 1826, when Lindley published his Capriccios and Exercises for the Violoncello. Only Duport had as yet composed lengthy cello etudes, which were included in his treatise, but unlike Duport’s, Lindley’s capriccios are of graded difficulty and do not methodically explore each key of the circle of fifths, although they do offer a variety of fingering patterns in related major and minor harmonies. Lindley also clearly expected his students to become skilled in playing double-stops, including thumb-position octaves and tenths.

The new approach to studying the cello offered by the Capriccios would soon become commonplace, as later cello teachers embraced the format. Caprices by Auguste Franchomme, Adrien Servais, and Lindley’s replacement at the Academy, Alfredo Piatti, were published in 1835, 1851, and 1865, while J. J. F. Dotzauer and Bernard Cossman added solo etudes to the cello repertoire in 1849 and 1876.

Reaction to Lindley’s etudes and capriccios was as positive and enthusiastic as it was to his playing and personality. When they were first published, the Harmonicon wrote: “We have here twelve pieces, nearly all of them in two movements,—one slow and one quick—and of two pages each; fingered in every doubtful passage, and calculated for a superior class of players, who may now obtain, at a moderate expense, the fruits of Mr. Lindley’s experience, carefully collected and ably digested.”

An obituary published in 1855 adds further insights into Lindley the musician and the man. It calls his life “calm, monotonous, and happy” but also added that he was “one of the greatest performers the art has known upon one of the most beautiful and difficult of instruments.” We are therefore grateful to Valerie Walden for not only making these works available in a fine edition but also for bringing to our attention the important role Lindley played in the history of cello playing.

Mark Kroll is the 2020 recipient of the Howard Mayer Brown Award for Lifetime Achievement in the Field of Early Music. His Sunday Baroque podcast interview with Suzanne Bona can be accessed at https://sundaybaroque.org/podcasts/mkroll.mp3