by

Published July 22, 2019

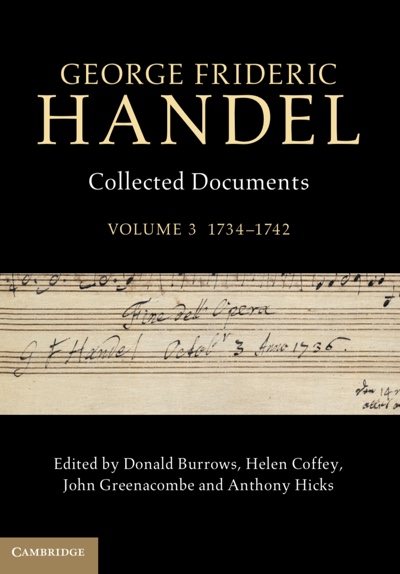

George Frideric Handel Collected Documents Volume 3 1734-1742. Compiled and Edited By Donald Burrows, Helen Coffey, John Greenacombe and Anthony Hicks. Cambridge University Press, 2018. xvi + 928 pages.

By Mark Kroll

If it can be said that the noted 18th-century writer and critic Samuel Johnson needed his Boswell (i.e., James Boswell, Johnson’s devoted biographer), then G. F. Handel needs his Donald Burrows. At the forefront of Handel research for decades, Burrows has contributed mightily to our knowledge about this great composer and to our appreciation and understanding of his music.

The latest contribution, a joint effort put together by Burrows and the distinguished Handel scholars Helen Coffey, John Greenacombe, and the late Anthony Hicks, is a magisterial multi-volume set that promises to include just about everything written about, by, to, and for Handel. The introduction to the recently published Volume 3, which covers the years 1734-1742, describes the scope of the project. (Volume 4, scheduled for publication on Sept. 19, will cover the years 1742-1750.) Volume 3 features “manuscript sources [that] include legal, institutional, financial and ecclesiastical records, as well as contemporary letters and diaries…London newspapers…with routine advertisements for theatre and concert performances, and for music publications…items in newspapers from European and Provincial British cities…[and] wordbooks, musical autographs and performing scores…examined systematically to confirm or establish casts and content for Handel’s performances. Documentary information concerning dates of composition is included, and musical revisions which relate to documented events are summarised.”

The latest contribution, a joint effort put together by Burrows and the distinguished Handel scholars Helen Coffey, John Greenacombe, and the late Anthony Hicks, is a magisterial multi-volume set that promises to include just about everything written about, by, to, and for Handel. The introduction to the recently published Volume 3, which covers the years 1734-1742, describes the scope of the project. (Volume 4, scheduled for publication on Sept. 19, will cover the years 1742-1750.) Volume 3 features “manuscript sources [that] include legal, institutional, financial and ecclesiastical records, as well as contemporary letters and diaries…London newspapers…with routine advertisements for theatre and concert performances, and for music publications…items in newspapers from European and Provincial British cities…[and] wordbooks, musical autographs and performing scores…examined systematically to confirm or establish casts and content for Handel’s performances. Documentary information concerning dates of composition is included, and musical revisions which relate to documented events are summarised.”

If that is not enough, we can also read about “the circumstances of Handel’s performances (such as orchestra lists, newspaper reports noting the arrival of his singers, and letters about their contracts)… items from diaries and registers…documents relating to recurring financial transactions… advertisements and notices for first nights of performances or revivals of works with which Handel was involved…and publications to which Handel subscribed.”

It is, of course, impossible to describe, or even list, everything found in these 944 pages. All I can do here is give a taste of what the full meal is like, and perhaps one way is to focus on a single work during this period. I have chosen one of my favorites: Handel’s oratorio Israel in Egypt.

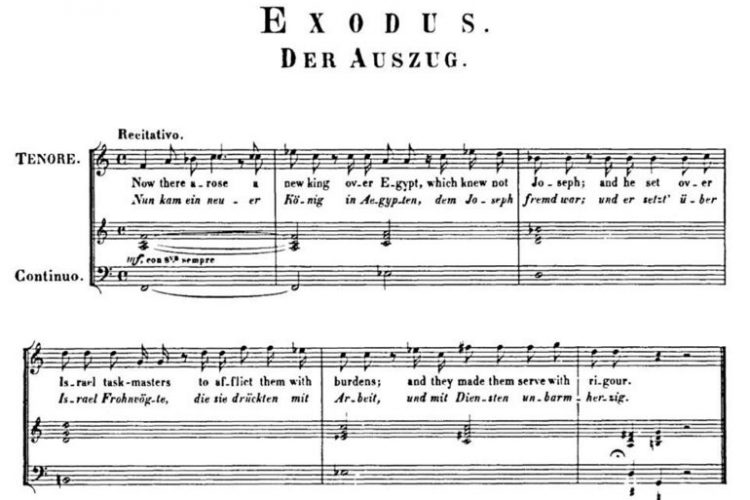

The first informative entry comes from October 2, 1738, when Handel indicates in his score that he has begun the composition of the oratorio: “angefangen [begun] Oct. 1 [or 2].1738.” On October 15, 1738, Handel writes that he has started Part II (“Act ye 2d 15 October 1738”) and on 20 October 1738 tells us the draft is finished: “Fine della Parte 2 da d’Exodus / Octobr 20. 1738.” By November 1, Handel can write that Part II is completely finished (“völlig geendiget”).

We next learn from an announcement in The Daily Advertiser that the first performance of Israel in Egypt will take place April 4, 1739: “AT the KING’s THEATRE in the HAY-MARKET…With several Concerto’s on the Organ, and particularly a new one.” Some music lovers, however, were worried about the subject, as we read in a letter from that time: “The Office of Licenser being grown almost as formidable to Authors, as that of Inquisitor to Jews and Hereticks, the Patrons and Lovers of Musick were in great Pain for the Fate of the new Oratorio…some Persons apprehending, with a deal of Reason, that the Title of Israel in Egypt was, to the full, as obnoxious as that of The Deliverer of his Country.”

Their concern might have been justified. A letter from April 9, 1739, complained that “Last Tuesday [4 April], Handel performed his second oratorio [Israel in Egypt] for the first time; but he did not have twenty people in the pit.” Undeterred, another performance on April 11 was announced in The London Daily Post and General Advertiser, although it was to be “shortned and Intermix’d with Songs” and supplemented by “two last new Concerto’s on the Organ.”

The turnout for this second performance was not much better, despite the praise of another letter writer on April 12, 1739: “I never yet met with any Musical Performance, in which the Words and Sentiments were so thoroughly Studied, and so clearly Understood.” Nevertheless, he also tells us that “the Polite attentive audience…was not Large enough,” and expressed his concern: “I should be extremely sorry to be deprived of hearing this again, and found many of the Auditors in the same Disposition,” worrying that “Mr. Handel will not undertake it without some publick Encouragem[en]t.” He urged the paper ”to convey not only my own but the Desires of several others, that he will perform this again in some time next week.” His strategy seems to have worked. We read in The Daily Advertiser of April 19, 1739: “I…congratulate, not Mr. Handel, but the Town, upon the Appearance there was last Night at Israel in Egypt…what a glorious Spectacle! To see a crowded Audience of the first Quality of a Nation.”

The book provides information about further performances of Israel in Egypt, such as one on May 18, 1739 (the program included Part III and the Funeral Anthem For Queen Caroline) performed by the Academy of Ancient Music at “the Crown and Anchor Tavern in the Strand. ”

The breathtaking detail for just one composition over a period of just one year will, I hope, give an idea of the treasures to be found in this book. Some are quite colorful and offer insights into the personal life of Handel and his contemporaries, such as the astrological symbols for the days of the week that Handel used in his musical autographs from September 1739 onwards, and the bank records for a £600 loan Handel secured from Hoare’s Bank.

To paraphrase the letter of April 19, 1739, cited above: I write to congratulate the authors of this book. What a glorious spectacle!

Volumes 6 and 7 of Mark Kroll’s recording of the complete Pièces de clavecin of François Couperin on Centaur Records have recently been released, as have the 2 volumes of The Art of Carol Lieberman. His books The Cambridge Companion to the Harpsichord and The Boston School of Harpsichord Building were published earlier this year.