by

Published September 24, 2018

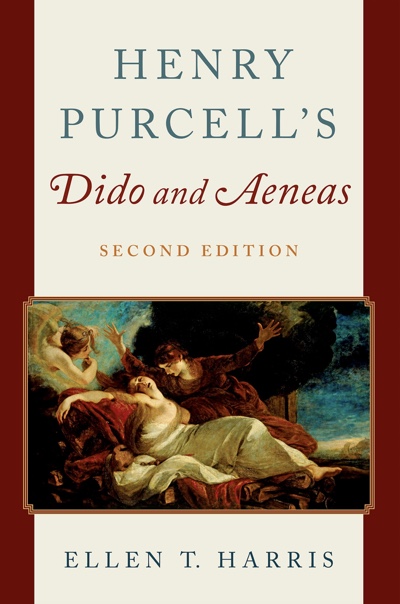

Henry Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas. Ellen T. Harris. Oxford University Press, 2017. 211 pages.

By Ryan James Brandau

I wouldn’t be surprised to learn that Ellen T. Harris enjoys reading mysteries and solving puzzles. It would help explain why she dedicated herself so thoroughly and enthusiastically to decades-long study of Henry Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas. The paucity of contemporaneous sources for the opera and relatively late date of musical material leaves us with a scant stack of sometimes conflicting, rarely corroborative resources. Add in the rotating cast of characters on the English throne in the 1680s, and it proves especially difficult to determine what exactly was written, when, for whom, and why.

Discoveries made since 1987, when Harris’s Henry Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas first appeared, haven’t made the things any clearer. As the headline on her 2017 New York Times article states: “The More We Learn About ‘Dido and Aeneas,’ the Less We Know.” Fortunately, Harris took on the “enthralling, humbling, and overwhelming” task of revising her 1987 volume. Three of its nine chapters are “in essence new”; others represent some combination of revision, expansion, and reinterpretation.

Discoveries made since 1987, when Harris’s Henry Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas first appeared, haven’t made the things any clearer. As the headline on her 2017 New York Times article states: “The More We Learn About ‘Dido and Aeneas,’ the Less We Know.” Fortunately, Harris took on the “enthralling, humbling, and overwhelming” task of revising her 1987 volume. Three of its nine chapters are “in essence new”; others represent some combination of revision, expansion, and reinterpretation.

Part One, “Background to the Music,” situates Nahum Tate’s libretto in literary and stylistic context. By comparing it to the Dido episode in Virgil’s Aeneid and Tate’s own play, Brutus of Alba, Harris highlights the ways Tate’s libretto sheds superfluous material to refashion the characterization of Dido and streamline the drama. Redeeming his infamous reputation, Harris demonstrates Tate’s skillful control of rhyme and imagery and celebrates his cohesive, complete, singable libretto — not second-rate Virgil but a new kind of “Restoration product.” She then tackles the problem of the unascertainable premiere. Harris dutifully walks us through scholarly attempts to use allegorical resemblances to the monarchs of the 1680s to posit possible premiere dates. Noting how “elastic” and “fungible” these allegorical interpretations can be, she asserts: “What will not do is choosing the one that seems best, or most appealing, as a way to date Dido and Aeneas.” She offers her and others’ more recent non-allegorical explorations of Tate’s libretto as Dido-focused tragedy, vis-à-vis Ovid’s Heroides and Tate’s own A Present for the Ladies.

Part Two, “The Music,” begins by presenting the discrepancies and lacunae among the sources closest to the work’s creation, clearly laying out the puzzle pieces for the reader. At last, in the fourth and fifth chapters, Harris gets into the nitty-gritty of Purcell’s music itself. Her insightful analyses illuminate on both the micro and macro levels why the opera sings and flows so beautifully and compellingly, showing how Purcell’s “revolutionary” handling of key, harmony, and musical declamation constitutes a “remarkable dramatic achievement” and a culmination of native English declamatory song style.

Her chapter on ground bass decodes the subtle mechanics of Purcell’s ingenious mastery of that technique. These sharp analyses have aged well and remain as engaging and enlightening as when I encountered their first version decades ago as an undergraduate entranced by the magic of Dido’s exquisite lament and eager to understand how Purcell managed to cast such a strong spell.

Part Three examines the performance history of Dido, revealing how it — like the various colorful reviews and essays she quotes at length — tells us as much about those eras as it does about the opera itself. New to this edition is her survey of the fascinating ways a period of “postmodernism” (1995 onward) marked a shift “away from efforts to recreate the opera ‘as it was’ and toward an embrace of relativism…pluralism…and irony,” via interpretations invoking psychology, gender, sexuality, and race.

Notably, she resists (or never had) the urge to anoint any one interpretation definitive, and her outlook remains decidedly ecumenical: “What is striking, and perhaps unique, about Dido and Aeneas is that practically all of the choices in the various recordings, videos, and articles can be and have been defended on the basis of one of the classical versions of the story, from the sources of the opera itself, or from literary and musical precursors, giving modern interpreters a wide range from which to choose.”

It seems she dove (again) into the multifaceted mystery surrounding this work because the fun is not just in trying to solve the mystery outright, but also in savoring the artistic bounty it has sown. I suppose it’s unsurprising, then, that her book lacks a conclusion. She doesn’t seem to want one, and neither should we. Her Times article makes the summary point that lies between the lines of the book and seems to have invigorated decades of inquiry: “The history of ‘Dido and Aeneas’ has only grown richer as we have discovered how little we actually know.” However the future of Dido unfolds, Harris’ comprehensive, concise, and well-organized volume will prove a durable, invaluable guide for musicologist, conductor, singer, stage director, dramaturg, or opera fan.

Ryan James Brandau is the artistic director of Amor Artis, a chamber choir and orchestra in New York City specializing in Renaissance, Baroque, and contemporary music. He also leads Princeton Pro Musica and the Monmouth Civic Chorus, and serves on the faculty of Westminster Choir College.