by Joshua R. Jacobson

Published May 16, 2022

Music and Jewish Culture in Early Modern Italy: New Perspectives. Lynette Bowring, Rebecca Cypess and Liza Malamut, eds. Indiana University Press, 2022. 297 pages.

Lynette Bowring, Rebecca Cypess, and Liza Malamut have collected 10 insightful and meticulously researched essays that shed light on Jewish musical activity in the Italian peninsula from the 14th to the 17th centuries. Unique to this time and place was an efflorescence of musical activity—in the sense of European “high culture”—and the authors point to the many instances of cultural, economic and social intercourse that brought this about. For the most part, Jews and Christians in Europe had occupied separate domains, not just religiously but culturally and geographically as well. Now, in defiance of church doctrine, Christian humanist scholars sought out Jews to teach them to read the Hebrew Bible in its original language. The printing press brought about an explosion of knowledge exchange, and Italy was the hub of this new media technology. Mobility (often enforced) had put many Jews in the forefront of international commerce to such an extent that many Christians relied on and interacted with Jewish bankers. Jews and crypto-Jews fleeing the Spanish Inquisition were welcomed in many areas of northern Italy. In fact, the institution of the first ghetto (Venice, 1516) was celebrated by many Jews as the establishment of a safe place to settle.

Lynette Bowring, Rebecca Cypess, and Liza Malamut have collected 10 insightful and meticulously researched essays that shed light on Jewish musical activity in the Italian peninsula from the 14th to the 17th centuries. Unique to this time and place was an efflorescence of musical activity—in the sense of European “high culture”—and the authors point to the many instances of cultural, economic and social intercourse that brought this about. For the most part, Jews and Christians in Europe had occupied separate domains, not just religiously but culturally and geographically as well. Now, in defiance of church doctrine, Christian humanist scholars sought out Jews to teach them to read the Hebrew Bible in its original language. The printing press brought about an explosion of knowledge exchange, and Italy was the hub of this new media technology. Mobility (often enforced) had put many Jews in the forefront of international commerce to such an extent that many Christians relied on and interacted with Jewish bankers. Jews and crypto-Jews fleeing the Spanish Inquisition were welcomed in many areas of northern Italy. In fact, the institution of the first ghetto (Venice, 1516) was celebrated by many Jews as the establishment of a safe place to settle.

The “new perspectives” in the title refers to the refutation of earlier studies by scholars with (hidden) agendas, who were intent on creating a narrative that united the Jewish people historically and geographically. The phrase “Jewish Music” itself was a nineteenth-century invention by authors such as the famous pioneering musicologist Abraham Z. Idelsohn. The current volume, although by no means the first to do so, assesses each artifact on its own merits, as well as in relation to relevant political and economic factors.

The authors focus on two phenomena: the participation by Jews in European musical culture and the creation of new Jewish musical artifacts that resulted from a fusion of the two cultures. In his essay, J. Drew Stephen points to the many famous Jewish dancing masters (including Jews who had been convinced to convert to Christianity), the most illustrious being Gugliemo ebreo da Pesaro. Gugliemo was the author of an influential treatise on the art of dancing published in 1463, taught dancing at the court of Urbino, and was sought after at major Italian courts for his skills at choreographing spectacles and organizing festivities. Dongmyung Ahn focuses on the Bassano family of Jewish musicians and instrument makers who, somewhat surprisingly, were recruited to travel from Venice to the English court of Henry VIII in a time when Jews had been banished from Britain. Bonnie Blackburn speculates on a Jewish origin for the renowned music theorist Pietro Aaron, and Luigi Sisto hypothesizes that several other musicians, such as Giovanni Tommaso Matino, may have had Jewish ancestry. But all this hypothesizing, with expressions such as “an apparent Hebrew origin,” or “suggests a connection to Jewish culture,” takes us into murky terrain, almost echoing the agendas of the “old perspectives.”

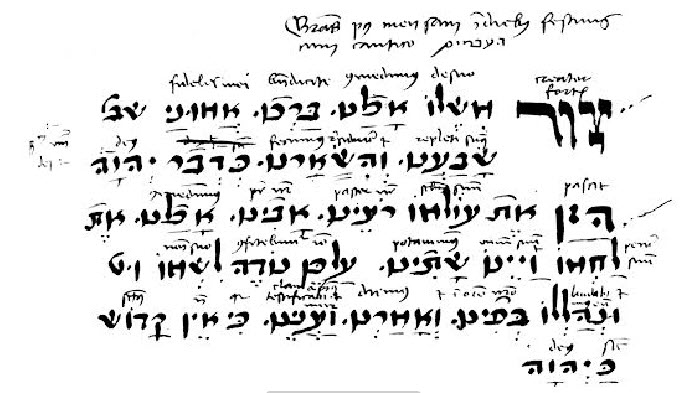

Several authors note that musical literacy was not absent from the Italian ghettos. For example, Francesco Spagnolo shows us a rare 17 th-century manuscript from Casale Monferrato in which a student, Ya’aqov Halewi Finzi, uses staff notation to transcribe a traditional synagogue chant he heard from his teacher, Cantor Avraham Segre. This may be the earliest notation of what for many centuries had been an exclusively oral tradition. In 1630 Rabbi Leon Modena established L’accadenia degli impediti in Venice, which, Liza Malamut writes, “assumed its role as an agent of modernity, melding art music, the ancient Hebrew language, and contemporary Jewish life.” On a slightly different tack, Avery Gosfield, noting that the early sixteenth-century Jewish poet Elye Bokher had instructed that his Yiddish poems be sung as contrafacts to specific tunes, suggests notated sources for two of these Hebrew melodies—one found in an exercise book by Johannes Renhart c. 1511, and one from the well-known 1724 transcriptions by Benedetto Marcello.

But the apex of this penetration of European art music into the Jewish ghetto is the volume of 33 Hebrew motets for the synagogue composed by Salamone Rossi and published in Venice in October, 1622, just 400 years ago. Much has been written about this path-breaking compendium of liturgical and para-liturgical music in which the Hebrew text of the Jewish liturgy is fused with the musical styles of the late Renaissance and early Baroque. As Stefano Patuzzi points out, in order to have this music performed there must have been enough Jewish men in the ghetto who were both musically literate and had the ability to read its lyrics in unvocalized Hebrew script. Furthermore, these bicultural singers had to coordinate the staff notation, which is read left-to-right, with the lyrics written in Hebrew letters running from right to left. Patuzzi explains that this fusion was not an abandonment of Jewish tradition, but rather a complement, “a simultaneous desire for cultural similarity and differentiation.” Indeed, Rossi’s champion, Rabbi Modena, cites the 14th-century Rabbi Immanuel of Rome, positing that choral music in Jewish worship was not a radical innovation but rather a reclamation of the music of the ancient Hebrews, which had been “stolen” by Christians. Focusing on the tension between orality and literacy, Cypess and Lynette Bowring in their chapter suggest how Rossi’s composed music introduced a new element into a liturgy that had been based exclusively on orally transmitted modal patterns and improvisation.

Bowring, Cypess, and Malamut’s collection provides valuable insights into this unique and colorful period of Jewish history, a zigzag of alternating oppression and acceptance, a complex of negotiated identities. If only the black and white reproductions had been printed in color.

Joshua R. Jacobson is professor emeritus at Northeastern University and the founder and artistic director of the renowned Zamir Chorale of Boston. He has written extensively on the music of Salamone Rossi.