by Wendy Heller

Published November 4, 2019

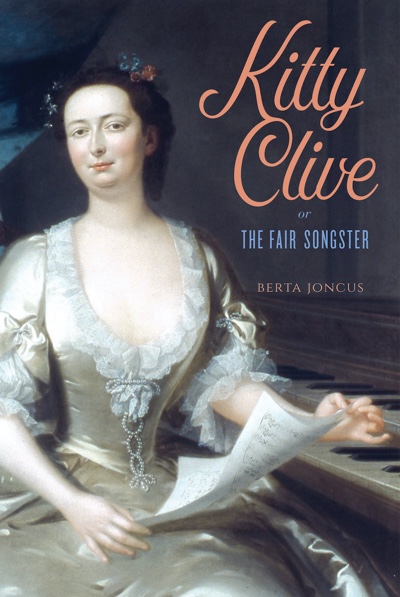

Kitty Clive, Or the Fair Songster. Berta Joncus. Boydell Press, 2019. x + 527 pages.

How might music historians best introduce readers to the soundscape of 18th-century London, a bustling city, where music of all sorts was vital to commercial, religious, political, and social concerns? Most of us immediately think of George Friderick Handel, whose image towers not only over 18th-century Britain, but also the history of European music. However, Berta Joncus’ brilliant new book, Kitty Clive or the Fair Songster, compels us to imagine London’s rich musical scene through the eyes and voice of one of the century’s most extraordinary performers: Kitty Clive (1711-1785), née Catherine Rafter. A gifted actress, singer, writer, and true celebrity, Clive commanded the London stage (especially Drury Lane Theater) for more than three decades.

Based on decades of meticulous historical research, Kitty Clive, or the Fair Songster reveals the mysterious alchemy that a gifted singer might harness to become a true celebrity: command over a broad spectrum of singing and acting styles; an impeccable sense of timing and rhythm; superb diction; a knack for managing one’s self-image; and an unerring instinct for how to captivate audiences of any social class. For Clive, as Joncus shows, it all began with an extraordinary singing voice that allowed her to “straddle” high and low rhetorical registers. Clive could compete with (or even mock) the best Italian sopranos; she could use the lower part of her voice to excel in popular songs and raunchy ballad operas on one night and employ her secure vocal technique the next day to become a goddess in a lofty masque. By playing so many different characters so persuasively, Clive (paradoxically) established a unique and powerful stage persona, one that (unlike so many of her colleagues) did not rely upon her desirability as a sex object. Instead, Clive used the stage to assert her authority, her moral superiority, and even her patriotism.

Based on decades of meticulous historical research, Kitty Clive, or the Fair Songster reveals the mysterious alchemy that a gifted singer might harness to become a true celebrity: command over a broad spectrum of singing and acting styles; an impeccable sense of timing and rhythm; superb diction; a knack for managing one’s self-image; and an unerring instinct for how to captivate audiences of any social class. For Clive, as Joncus shows, it all began with an extraordinary singing voice that allowed her to “straddle” high and low rhetorical registers. Clive could compete with (or even mock) the best Italian sopranos; she could use the lower part of her voice to excel in popular songs and raunchy ballad operas on one night and employ her secure vocal technique the next day to become a goddess in a lofty masque. By playing so many different characters so persuasively, Clive (paradoxically) established a unique and powerful stage persona, one that (unlike so many of her colleagues) did not rely upon her desirability as a sex object. Instead, Clive used the stage to assert her authority, her moral superiority, and even her patriotism.

She did so in the most varied repertoire imaginable: in the valuable appendices to the volume, Joncus documents more than 222 roles that Clive performed 1728-1769. The list includes tragedies, comedies, pastorals, ballad operas, masques, and operas, in which she sang and spoke words by Shakespeare, Milton, Dryden, Molière (in translation), Fielding, Congreve, and Jonson, as well as her own texts. Her repertoire, moreover, not only featured popular songs, but music by composers such as Handel, Thomas Arne, William Boyce, and John Gay. Clive’s career was shaped as well by her many “lines” — that is, the stereotypical roles with which she was associated: goddesses, sentimental heroines (including spirited and abused wives), country girls in the city, defiant daughters, fine ladies, intriguing servants, patriot sopranos, Shakespearean heroines, and, of course, Kitty Clive herself.

Clive’s was not a simple life, nor did she leave an uncomplicated trail for the biographer. The details of her marriage to George Clive in 1733 remain murky, if it actually happened at all. The pretense of a marriage seems to have provided him with a cover for his relationships with men, allowing Kitty to acquire the respectable name of a high-ranking family. Perhaps what is most exciting is the way that Joncus’ “thick” history takes us into the rough-and-tumble world of British theater: financial disasters and critical flops, the competition between players and managers, the good press and the bad press, and the accidental successes and unexpected failures that swallowed up and spit out one artist after another. Clive, however, had a knack not merely for surviving, but also triumphing, repeatedly besting some of her most famous male collaborators, such as the tenor John Beard and actor David Garrick.

But even more than providing us with a slice of history and a glimpse into the life of an intriguing woman, Kitty Clive, or the Fair Songster opens up entirely new ways of thinking about how a singer might wield her voice. Joncus does not so much invoke the abstract concept of “Voice,” but rather helps the reader imagine the specific grain of a very specific instrument with which Clive was identified throughout her long career. What is particularly fascinating is the extent to which Clive’s musicianship and ability as a singer became the catalyst for all that followed. Joncus persuasively shows how her musical skill helped her excel in the spoken theater, pointing out the extent to which control of tempo, rhythm, and melody are essential for stage speech, a point that musicians and actors rarely acknowledge today.

Readers of Early Music America will be fascinated by this beautifully written biography, full of intriguing anecdotes and astute cultural criticism, where backstage gossip on one page is followed by keen musical analysis on the next. Moreover, singers will discover an entirely new repertoire to explore, one that puts the music of Handel and his contemporaries into a much clearer focus. Clive is a heroine for all generations, and Berta Joncus is to be praised for letting us hear her voice so clearly today.

Wendy Heller is the Scheide Professor of Music History and Chair of the Department of Music at Princeton. Her most recent publication is the co-edited volume Performing Homer: The Voyage of Ulysses from Epic to Opera (Routledge, 2019), and she has previously published Emblems of Eloquence: Opera and Women’s Voices in Seventeenth-Century Venice (University of California Press, 2003) and Music in the Baroque Era (W. W. Norton, 2013). Heller’s critical editions of Francesco Cavalli’s Veremonda l’Amazzone di Aragona and Handel’s Admeto are forthcoming.