by

Published March 11, 2019

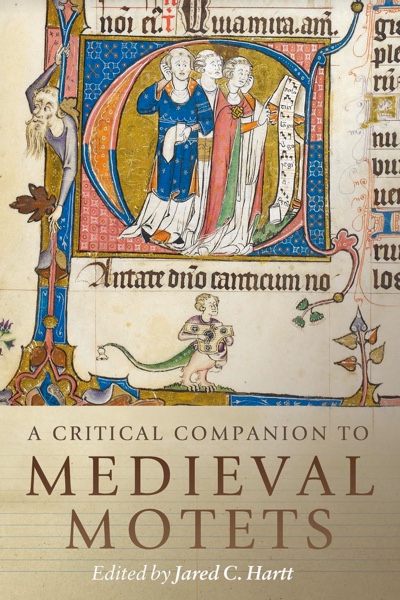

A Critical Companion to Medieval Motets. Edited by Jared C. Hartt. The Boydell Press, 2018. 397 pages.

By Samantha Bassler

This impressive volume features scholarly experts critically engaging with the evolution of the Medieval motet — a genre difficult to define, despite its influence on the development of rhythm, notation, and polyphony. The goal of the Companion is to define the motet genre as pluralistic and multifaceted in style, giving space to both French- and English-language motets, tackling old and new debates in motet scholarship alongside new approaches to the evolution of music notation and the motet.

The book, which is aimed not only at specialists but also at upper-level undergraduates, graduate students, and anyone interested in learning more about Medieval motets, is comprehensive, tackling questions of genre, origins, composition, chant, notation, function, manuscript culture, language, style, the influence of important composers and collections, and more. To this end, the book includes a glossary of terms and an index of cited motets with information about manuscript sources.

The book, which is aimed not only at specialists but also at upper-level undergraduates, graduate students, and anyone interested in learning more about Medieval motets, is comprehensive, tackling questions of genre, origins, composition, chant, notation, function, manuscript culture, language, style, the influence of important composers and collections, and more. To this end, the book includes a glossary of terms and an index of cited motets with information about manuscript sources.

The Companion consists of 17 chapters, each divided into two sections: The first investigates the motet’s genre, origins, composition, isorhythm, notation, function, and manuscript culture, while the second features case studies of 13th- and 14th-century motets from both France and England. Throughout, the Companion engages with questions of text painting and setting, examining how the textual aspects of motets integrate with the auditory and musical aspects. Elizabeth Eva Leach’s first chapter emphasizes the difficulty of describing and defining the motet as a genre: that distinguishing the motet from similar works, like clausulae, conductus, or songs, is not straightforward. Focusing on the manuscript Douce 308 from Oxford’s Bodleian Library, Leach problematizes the traditional narrative of Medieval motets originating from Latin clausulae, arguing that the genre is an example of musical hybridity. Catherine Bradley also investigates motet origins, recommending the study of surviving notated sources of similar genres, and the great potential for variety and flexibility in the motet, clausula, and conductus.

The topics of the next several chapters revisit debates in motet scholarship. Alice V. Clark reconsiders the relationship of the tenor voice to the compositional method of motets, arguing that the tenor voice occupied a variety of roles, and suggests a stratification of voices to synthesize stylistic differences in motets. Lawrence Earp deals with the term isorhythm, which since its introduction is frequently debated as to its usefulness for understanding motets. Karen Desmond’s fifth chapter focuses on the transmission of motets and their differing notation systems in multiple manuscripts, revealing how music is represented across the Medieval period.

Dolores Pesce examines the functions of motets in the 13th century, with examples from motets based on the chant fragment portare, and demonstrates how motets blend the singing tradition of the Roman Catholic Church with vernacular refrains from the courtly love tradition. Jacques Boogart delves further into the interdisciplinary nature of the motet, illuminating exchanges of ideas between 14th-century poet-composers, mixing together sacred, secular, and political content. John Haines and Stefan Udell delve into manuscript culture, exploring the ways in which motets were laid out in extant manuscripts, while Jennifer Saltzstein examines the role of clerics and courtiers in the vernacular two-voice motets. Through an intertextual analysis of the motet’s musical and poetic structure, Saltzstein sheds new light on the audience and cultural functions of the ars antiqua motet.

In Chapter 10, Suzannah Clark contrasts polytextuality in the 13th-century motet with monotextual examples in the Montpellier codex, casting musical style in the Middle Ages as a pursuit of contrast. This complements the chapter by Gaël Saint-Cricq, which explores 13th-century chansonniers outside of Paris, arguing for a confluence between chanson and motets in the period. Matthew Thomson’s chapter on polyphonic motets and monophonic songs also connects to Saint-Cricq’s work, exploring three specific examples of motet voices quoting first stanzas from monophonic songs. In Chapter 13, Jared C. Hartt explores genre, tonal coherence, and reconstruction in English motets, demonstrating unique characteristics compared to continental motets.

Anna Zayaruznaya compares the chant that formed the basis of Phillippe de Vitry’s Colla/Bona motet to the finished product and reveals aspects of the compositional process. Margaret Bent examines Machaut’s Motet 10 and argues for the crucial role of text-music relationships to an understanding of style, while Sarah Fuller embarks on a textual and musical analysis of Machaut’s Motet 22. Finally, Emily Zazulia ponders the dating of the motet Portio nature/Ida capillorum, recasting the scholarly narrative of musical style evolution as tenuous and more problematic than traditionally assumed.

A Critical Companion to Medieval Motets is an excellent introduction to fascinating topics in early musicology, thoroughly investigating the Medieval motet from angles that will intrigue anyone interested in Medieval music.

Samantha Bassler is a musicologist of early-modern English music with particular interests in cultural studies, disability studies, gender, and reception history. She is an adjunct professor of music at New York University and Rutgers University at Newark, and the owner of a piano studio in Brooklyn, NY.