by Valerie Walden

Published September 7, 2020

Before the Baton: Musical Direction and Conducting in Stuart and Georgian Britain. Peter Holman. The Boydell Press, 2020, 405 pages.

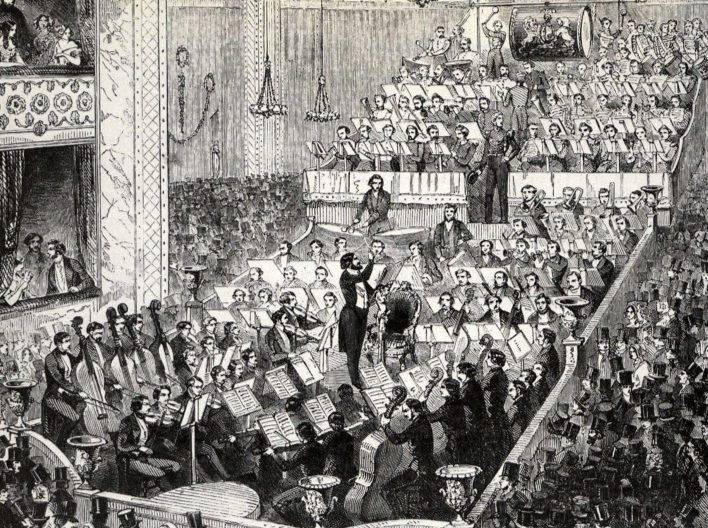

This is a beautiful book to hold, even before reading what is inside. While, of course, one should not judge a book by its cover, its thick glossy pages and luxurious illustrations provide great motivation to open it up and read its contents.

Peter Holman’s musicology is aimed at serving performance. From his experience, he believes that “conducting as a subject suffers particularly from anachronistic assumptions derived from modern practice.” To make his case, he uses a variety of sources, inclusive of first-hand performance descriptions, iconography, and score analysis, taking aim at certain contemporary assumptions about 17th-, 18th-, and early 19th-century performance practice.

Peter Holman’s musicology is aimed at serving performance. From his experience, he believes that “conducting as a subject suffers particularly from anachronistic assumptions derived from modern practice.” To make his case, he uses a variety of sources, inclusive of first-hand performance descriptions, iconography, and score analysis, taking aim at certain contemporary assumptions about 17th-, 18th-, and early 19th-century performance practice.

The book begins with a general history of “time beating” in continental Europe, Holman’s major point being that no batons are in evidence in most early sources but rather only hand motions or the use of a rolled-up piece of paper or parchment. Holman’s use of sources, however, is a bit disappointing, since he too often relies on the secondary rather than primary documentation. For example, he mentions Martin Agricola’s Musica figuralis deudsch, but rather than citing Agricola’s treatise directly, he relies on Anne Smith’s 2011 publication The Performance of Sixteenth-Century Music: Learning From the Theorists. Nevertheless, the information about how vocalists (most of his examples are from the Italian polychoral performance practices of Italy and Germany, with and without instrumental accompaniment) maintained ensemble is very interesting.

The book then divides into two parts, each with four chapters; part one examines the conducting of choral music, part two the direction of opera and theater music. Although Holman’s study of choral conducting is not exclusive to a study of Handel, he is the central figure, and the detail Holman presents about Handel’s thought processes, conducting style, musical goals, and influence goes to the core of this book. We also learn much about Handel’s organ playing, both in continuo passages and melodic applications. Holman’s amusing anecdotes about Handel’s volatile rehearsal techniques make this orchestral cellist aware that Toscanini was not the first or only conductor to shred his players’ egos.

Holman’s analysis of the musical organization in early English theater productions, beginning with 17th-century English masque performances, is instructive. At times, apparently, musicians were grouped into small ensembles of winds or strings needing no conductor, and although Holman traces 17th-century examples of “time beating” back to 1607, with a performance of Thomas Campion’s Lord Hayes Masque, he claims that this form of centralized authority remained the exception, rather than the rule in English performance. He believes the use of a “time beater” began primarily with the productions of Mathew Locke and then Henry Purcell.

Holman continues with an explanation of how theater music and opera were conducted from the continuo section (harpsichord, cello, archlutes or theorbos, and double basses) or from the violin. Here, we meet London’s most recognized performers, both foreign-born and domestic: Handel, again, but also other harpsichordists, cellists, and violinists. Holman knows this material well and presents details about who worked with whom and who played what, where, and when, making for a vivid portrait of English musical life during this period. Some of his first-hand accounts are particularly colorful, such as the time a group of young men, unhappy at the absence of a favorite dancer from a performance at the Drury Lane Theater, rioted and smashed a harpsichord “into shivers.”

The final chapter of the book examines how the modern concept of baton conducting came to England from France and Germany, where conductors, as we understand the term, were leading opera orchestras by the end of the 18th century. English objections to the practice, according to Holman, were based primarily on nationalistic hubris. He discourses on the gradual introduction of the baton in three key performance arenas — opera, orchestra, and choral — tracing the gradual change from the orchestra being led from the keyboard or violin to a person with a baton, the harpsichord still used as the keyboard instrument for opera orchestras in London until 1810. By then, however, cellist Robert Lindley and bassist Domenico Dragonetti had become the dream team of the continuo section in the opera or oratorio orchestras. The author describes the performance style of the two men and makes the point that in productions in which they played, a keyboard was dispensed with entirely until 1837, when their style of playing then came to be seen as antiquated and use of the piano became the norm.

After this discussion, orchestral performance, itself, is examined through materials about the Philharmonic Society, with a brief look at 19th-century English choral conducting as seen through the experiences of Sir George Smart. In his examination of the Royal Philharmonic Society, Holman uses well-known quotations from Louis Spohr, François-Joseph Fétis, and Felix Mendelssohn to argue his point that Spohr took too much credit for introducing the baton to English orchestras. Holman shows much greater regard for Mendelssohn but misses an important component of Mendelssohn’s musical approach by barely acknowledging the major contributions made to the conducting of the Philharmonic Society by Mendelssohn’s teacher and life-long mentor, Ignaz Moscheles, who lived in London from 1825-1846, led the Philharmonic Society for numerous concerts, and made many improvements in rehearsal practices during his tenure as both a Director of the Society and guest conductor. It is particularly disappointing that Holman did not acknowledge Moscheles’ most notable achievement in this regard: conducting, with a baton, the first fully successful performance in England of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony in 1837 and repeating that success in 1838 and 1841.This information would have lent important detail to this section.

It is also clear that Holman uses this book to support his beliefs about historically informed performance practice, which he summarizes in a short postlude. Coming full-circle from the Introduction, he reiterates his argument that pre-19th century music should be performed without a central, baton-waving conductor. In this regard, Holman’s approach seems entirely justified.

Valerie Walden’s book, One Hundred Years of Violoncello; A History of Technique and Performance Practice, 1740-1840, has just appeared in a Japanese translation published by Douwa Shoin. Her edition of the music of the noted 19th-century London cellist Robert Lindley has recently been published by Bärenreiter.