by

Published January 14, 2019

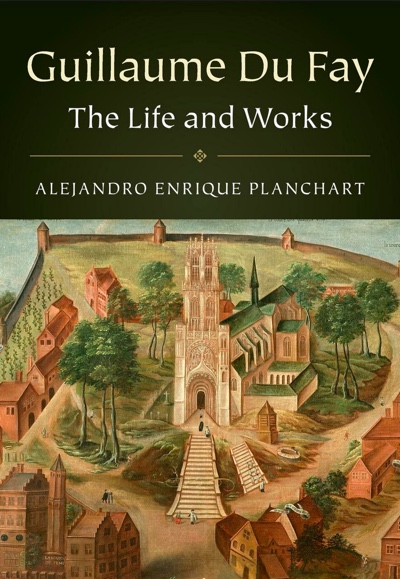

Guillaume Du Fay: The Life and Works. Alejandro Planchart. Cambridge University Press, 2018. 2 vols., 926 pages.

By William Watson

The product of over 40 years of research, Alejandro Planchart’s monumental study of the life and works of Guillaume Du Fay is sure to become the new standard reference work on its subject. Planchart would be the first to point out that his effort does not stand alone — his close engagement with decades of scholarship on Du Fay demonstrates as much — but as an exemplary specimen of its genre, this monograph seems bound to cast a long shadow. To put it briefly, the book humbles its reader.

Planchart divides his study into two volumes: The first deals largely with Du Fay’s life, the second with his works. The “life” volume consists of six chapters that explore delimited portions of Du Fay’s biography: origins and first years in Cambrai (1397–1414), early career, time in the papal chapel and at the court of Savoy, return to Cambrai in 1439, a second Savoyard sojourn in the 1450s, and his final retirement at Cambrai until his death in 1474. A prologue examining the changing social and ecclesiastical status of practical musicians in the years and centuries prior to Du Fay’s birth and a brief seventh chapter outlining the reception of Du Fay and his music after his death round this volume out.

Planchart divides his study into two volumes: The first deals largely with Du Fay’s life, the second with his works. The “life” volume consists of six chapters that explore delimited portions of Du Fay’s biography: origins and first years in Cambrai (1397–1414), early career, time in the papal chapel and at the court of Savoy, return to Cambrai in 1439, a second Savoyard sojourn in the 1450s, and his final retirement at Cambrai until his death in 1474. A prologue examining the changing social and ecclesiastical status of practical musicians in the years and centuries prior to Du Fay’s birth and a brief seventh chapter outlining the reception of Du Fay and his music after his death round this volume out.

Planchart’s lucid presentation and grounding in the documentary evidence are definitive assets. Whether walking through how Du Fay’s birthdate can be determined, weighing the evidence suggesting that Du Fay’s mother may have been a survivor of rape, or arguing in the face of a seeming documentary lacuna that Du Fay was master of the small vicars (the singers) at Cambrai Cathedral in the years just prior to his death, Planchart deliberately lays out each stage of his argument and its support in the extant documentation, often in considerable detail. As a result, his study rewards the critical and cautious reader as much as it does the voracious and eager.

The “works” volume opens with a short but forceful contention — which is also perhaps the major overarching argument of Planchart’s study — that Du Fay, unusually for the 15th century, thought of himself primarily as something very close to a modern composer. The remaining eight chapters each describe a generic subcategory of Du Fay’s compositions: the “isorhythmic” and mensuration motets, the cantilena and “new-style” motets, music for the Office, settings of individual movements of the Ordinary of the Mass, settings of the Proper of the Mass, the early Ordinary cycles (to 1450), the late Ordinary cycles, and finally the songs. Planchart’s musical analyses are perceptive and often evocative, particularly his comments on the melodic construction of the plainsong settings Du Fay wrote in the 1450s and his thoroughgoing concern with texture as a marker of form and structure in Du Fay’s music.

That these observations are products of a close familiarity with Du Fay’s music garnered over a lifetime of performance and study is made clear through Planchart’s occasional interjections wherein he describes, for instance, how some particular relations of tempo only crystallize in performance, or how certain “cross-relations” of musica ficta change dramatically between the notes on the page, private realization at the keyboard, and performance by vocal ensemble. These asides constitute some of the book’s most delightful moments. The incredibly rich appendices at the back of the “works” volume — which include lists of every small vicar and officially sanctioned pedagogue employed at Cambrai Cathedral during the 15th century, Du Fay’s will, accounts of its execution presented to the cathedral chapter, and an inventory of his estate, altogether amounting to over 200 pages — further cement this study’s status as the new go-to reference for research on Du Fay.

Perhaps due in part to its long gestation and broad scope, parts of Planchart’s study are effectively “detachable” from the rest of the book and might be productively read in isolation by those interested in such matters as the social hierarchy of Cambrai Cathedral, Du Fay’s ecclesiastical career, and the shifting status of illegitimate children in the later Middle Ages. This detachability extends to Planchart’s tendency to reintroduce, at length, certain key documents and arguments many times over the course of the book.

These frequent repetitions, along with a number of small but troubling errors (e.g., cross-references — particularly in the first volume — are sometimes vague or even incorrect; and the date of Du Fay’s death is erroneously given in the main text as “17 November,” though an accompanying footnote correctly identifies it as “xxvii novembris”) suggest that the manuscript might have benefited from additional editing.

Such small points aside, this book is bound to have a long and fruitful reception, and stands as a testament to not one but two extraordinary sets of lives and works: its subject’s and its author’s.

William Watson is a Ph.D. candidate in historical musicology at Yale University. His research focuses on the circulation of polyphonic vernacular song in 15th-century Europe.