by K. Dawn Grapes

Published November 15, 2021

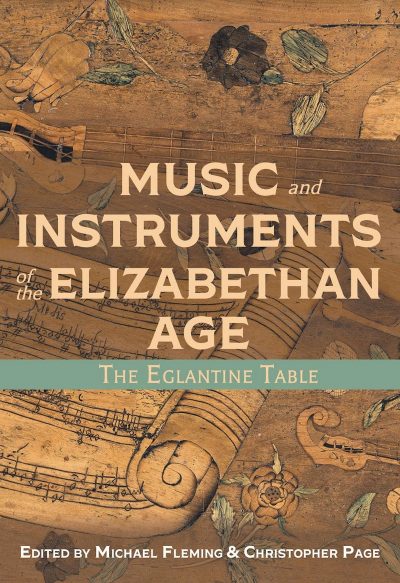

Music and Instruments of the Elizabethan Age: The Eglantine Table. Michael Fleming and Christopher Page, eds. Boydell Press, 2021. 291 pages.

It may seem odd to read a review of a book about a piece of furniture on a website devoted to early music. England’s Eglantine Table, however, is no ordinary household artifact. What makes the Eglantine Table so special? Built sometime around 1568, the upper layer of the original wooden top was removed and replaced with bits of selected woods and other materials, arranged to depict important objects of the time, in a unique display of marquetry and inlay. Restored in 1996, the table remains an object of great interest at Hardwick Hall, a grand country estate in the UK, where it is on display.

The title that editors Michael Fleming and Christopher Page chose for the book, Music and Instruments of the Elizabethan Age: The Eglantine Table, justly places a focus on the musical items portrayed on the tabletop, for at least 15 musical instruments appear alongside music as it would have been notated at the time. Many objects are realized at close to actual size, and although artistic modifications were made to show parts of instruments not normally viewable from a single angle, in many cases it seems that the original artists based their work on carefully considered models. The instruments are found alongside images of non-musical items such as cards and game boards, floral filigree, and writing implements, as well as heraldry specific to the Cavendish and Talbot families. This wonder of craftsmanship was likely a wedding gift for the family of Bess of Hardwick, the family matriarch who was one of the richest and most powerful women of the Elizabethan era.

The title that editors Michael Fleming and Christopher Page chose for the book, Music and Instruments of the Elizabethan Age: The Eglantine Table, justly places a focus on the musical items portrayed on the tabletop, for at least 15 musical instruments appear alongside music as it would have been notated at the time. Many objects are realized at close to actual size, and although artistic modifications were made to show parts of instruments not normally viewable from a single angle, in many cases it seems that the original artists based their work on carefully considered models. The instruments are found alongside images of non-musical items such as cards and game boards, floral filigree, and writing implements, as well as heraldry specific to the Cavendish and Talbot families. This wonder of craftsmanship was likely a wedding gift for the family of Bess of Hardwick, the family matriarch who was one of the richest and most powerful women of the Elizabethan era.

This collection of essays inspired by the table should appeal to many kinds of readers — students, scholars, musical instrument lovers, Anglophiles, history buffs, and early-music aficionados included. The volume features 16 chapters and two appendices, each written by an expert. All are approachable and accessible even to those without expert knowledge. The book is divided into three main sections. The first includes an introduction that serves as a general overview, followed by commentaries on the non-musical items depicted on the table. The editors have done an impressive job compiling a cohesive volume. Rather than simply collate a set of essays with a common subject, as is typical for so many books like this, chapter authors cross-reference each other, as well as the appendices and figures, with a common narrative voice. As interesting as the initial articles are, drawing on questions most of us have never considered (How did they keep from drawing too much ink onto the quill? What were the hidden meanings of certain types of plants? Why was chess a “good” game and dice games disreputable?), it is the central section on notated music and musical instruments that serves as the heart of the book.

John Milsom’s and Matthew Spring’s articles on notated music and tablature not only describe how music was presented in print and manuscripts of the time but also go so far as to reconstruct the music displayed on the tabletop. Practitioners will recognize the names of many of the authors of essays focusing on individual instruments, including Fleming (bowed strings), Page (guitar), Matthew Spring (lute), Peter Forrester (cittern), Karen Loomis (harp), and the late Jeremy Montagu with Graham Wells (winds). Each follows a general outline, with background on the instrument, commentary on how accurately the item is depicted on the table, comparisons to other contemporaneous images of the instrument, and an assessment of what types of people would have played or listened to each instrument and in what locations

While listings of physical specifications might get tedious to the average reader, they will be especially useful to students or researchers looking for detailed information related to Elizabethan instruments of the time. Both professionals and amateur players will certainly be intrigued by chapters on their own instruments, where historical tidbits and information on organological development and study are provided.

The final group of three chapters seeks to contextualize the table’s images in relation to their historical era and to each other. Of special note are chapters by Milsom and by Christopher Marsh that, side-by-side, portray the differences between Elizabethan amateurs practicing and listening to domestic music and professional musicians, who would have been heard not only inside upper-class homes but also in public establishments. In the foreword, readers are informed that the volume “conveys an exceptional sense of music as a variegated experience,” and this is but one example of how the authors succeed in this goal.

The numerous illustrations and images in this book are especially impressive, including 16 detailed, color photographic plates provided by the National Trust, the charitable organization that maintains the estate where the table resides. The ability to reference these photos allows readers to fully envision the text and adds appreciation for the skills needed to create this functional piece of artwork.

Music and Instruments of the Elizabethan Age: The Eglantine Table provides a wealth of information. While one could read straight through, cover-to-cover, readers might better appreciate the content if they approach the volume in small chunks in order to allow time to really consider each author’s narrative. For while you may not be able to judge a book by its cover, sometimes a tabletop is so impressive that it deserves continued inspection some 450 years later.

K. Dawn Grapes is an Associate Professor at Colorado State University and author of the books With Mornefull Music: Funeral Elegies in Early Modern England (2018) and John Dowland: A Research and Information Guide (2020).