by

Published October 22, 2018

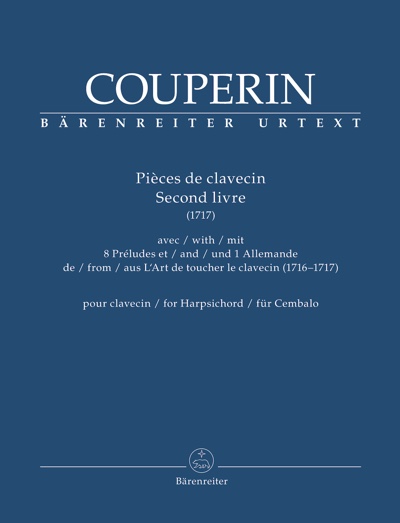

Couperin, Pièces de Clavecin, Seconde livre (1717) avec 8 Préludes et 1 Allemande de L’Art de toucher le clavecin (1716-1717). Denis Herlin, editor. Bärenreiter, BA 10845 (2018). 295 pages.

By Mark Kroll

Keyboard players born after 1960 might be surprised to learn that the edition of choice for François Couperin’s pièces de clavecin during the first 70 years of the 20th century was not only published by Augener between 1888-1889, but also was edited by Friedrich Chrysander and Johannes Brahms. Yes, that Brahms. He was a passionate advocate of early music, much to the bewilderment of his colleagues and close friends, such as Clara Schumann, who wrote in her diary on September 26, 1876, after receiving Brahms’ birthday gift of Couperin’s music: “…except for a few things they are really of little interest musically.”

Liszt was even more negative, and about all French music. It was reported that he “sneered the whole time while someone played Rameau’s Gavotte and Variations” in one of his master classes. Brahms remained undeterred. In addition to Couperin and Bach, he reportedly owned 300 sonatas of Domenico Scarlatti and even used the opening measures of Scarlatti’s Sonata in D major, K. 223 to begin his song Unüberwindlich, Op. 72, No. 5.

Liszt was even more negative, and about all French music. It was reported that he “sneered the whole time while someone played Rameau’s Gavotte and Variations” in one of his master classes. Brahms remained undeterred. In addition to Couperin and Bach, he reportedly owned 300 sonatas of Domenico Scarlatti and even used the opening measures of Scarlatti’s Sonata in D major, K. 223 to begin his song Unüberwindlich, Op. 72, No. 5.

The Brahms-Augener edition, as we called it, was supplanted between 1969-1972 by Kenneth Gilbert’s wonderful set of the complete Couperin pièces de clavecin for Heugel in its “Pupitre” series. This remained the gold standard until the publication of the first two volumes of Bärenreiter’s projected complete set of all four books. They are indeed cause for celebration: They are superb, and set new standards, both as a performance edition and a scholarly resource.

I reviewed Volume 1 in another journal last year, and I am happy to report that this second volume is equally excellent. The preface is particularly notable, and is so comprehensive that it could stand alone as a scholarly article on the subject. In it, we learn about the circumstances in Couperin’s life when the pieces were composed and published, including the important fact that, in the case of Book II, Louis XIV had recently died. We are even given a list of addresses of the houses in which Couperin lived, allowing one to imagine knocking on his door, simply to say bonjour. There are also probing discussions about the genesis of the compositions, many having been written years before their publication, and their engraving, publication, and reception. The overall structure of the second book is analyzed, and editor Denis Herlin offers valuable information about tempo markings, ornaments, and the harpsichords Couperin knew.

The editor also addresses some notational issues here, such as the thorny question about the differences between curved and square slurs in Couperin’s music, and he offers other insights into performance practices of the time. This includes an extensive glossary that provides, in easy-to-use format, “Directions for Performance” in both French and English.

The layout of the music is equally praiseworthy, its large format making it as clear and eminently readable as the 18th-century original, which was a magnificent example of French engraving. And like that original, Herlin and Bärenreiter set out to avoid all page turns within pieces, as did Couperin’s publisher. This is a difficult task that takes great planning and care, but editor and publisher here have succeeded admirably, and were only forced to use page turns in three, very long pieces: the Passacaille, the Allemande à deux Clavecins, and La Triomphante. This absence of page turns is a particularly useful feature of these volumes, and is something that no other modern edition has been able to achieve.

The “Critical Commentary” is as impressive as that of Volume 1. Herlin seems to have consulted more than 50 printed and manuscript sources for both the second book of the pièces de clavecin and L’Art de toucher le clavecin, instilling the reader and performer with great confidence that the text offered by Bärenreiter represents, as closely as possible, Couperin’s final intentions.

Peter Bloom’s translation from French to English is excellent, and it was interesting to note that in this volume he made small, subtle changes from what he had used in Volume 1 in order to make the translation even more idiomatic.

Bärenreiter tells me that Book III of Couperin’s pièces de clavecin will be published around the middle of 2019 and that the final volume will appear several years after that. This is good news for harpsichordists, and for Couperin.

Two publications by Mark Kroll will appear in 2019: The Cambridge Companion to the Harpsichord and The Boston School of Harpsichord Building: William Dowd, Eric Herz and Frank Hubbard Personal Reminiscences by the People Who Knew and Worked With Them. Volumes 6 and 7 of his complete recording of Couperin’s pièces de clavecin will also be released soon.