by Suzanne Westfall

Published November 16, 2020

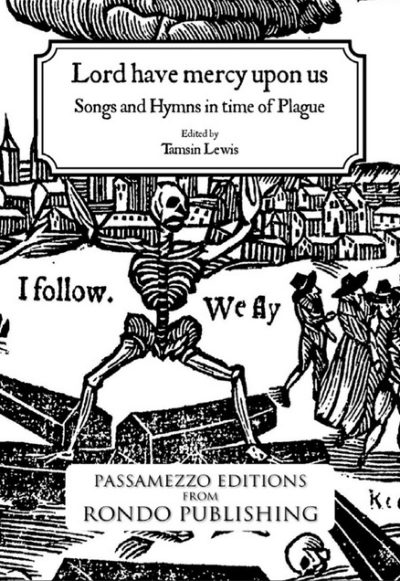

Lord Have Mercy Upon Us: Songs and Hymns in Time of Plague. Tamsin Lewis. Rondo Press, 2020. 30 pages.

What could be more appropriate than a reminder that we have lived through plagues before, from Exodus to periodic visitations in Europe from the 14th to 17th centuries to more modern iterations of the AIDs and Ebola viruses? And spot on, on cue, comes Tamsin Lewis with Lord Have Mercy Upon Us: Songs and Hymns in Time of Plague.

Lewis’s edition includes eight selections placed in historical context and meticulously arranged for today’s musicians, with an extensive bibliography. Her introduction (which ends appropriately with the acrostic “Stand farther off” from Henry Petowe’s 1625 The Countrie Ague) is laced with tasty morsels, from Daniel Defoe’s fictional A Journal of the Plague Year (written in 1722 about the plague of 1665, likely based on the journals of his uncle) to playwright Thomas Dekker’s reportage of plague scenes for his pamphlet Rod for Runaways. Most haunting is her selection from Defoe: “All the plays and interludes… were forbid to act; the gaming-tables, public dancing-rooms, and music-houses… were shut up and suppressed; and the jack-puddings, merry-andrews, puppet-shows, rope-dancers, and suchlike doings… shut up their shops, finding indeed no trade.”

Lewis’s edition includes eight selections placed in historical context and meticulously arranged for today’s musicians, with an extensive bibliography. Her introduction (which ends appropriately with the acrostic “Stand farther off” from Henry Petowe’s 1625 The Countrie Ague) is laced with tasty morsels, from Daniel Defoe’s fictional A Journal of the Plague Year (written in 1722 about the plague of 1665, likely based on the journals of his uncle) to playwright Thomas Dekker’s reportage of plague scenes for his pamphlet Rod for Runaways. Most haunting is her selection from Defoe: “All the plays and interludes… were forbid to act; the gaming-tables, public dancing-rooms, and music-houses… were shut up and suppressed; and the jack-puddings, merry-andrews, puppet-shows, rope-dancers, and suchlike doings… shut up their shops, finding indeed no trade.”

Sound familiar?

Lord Have Mercy on Us offers the reader/performer a grisly banquet to entertain us in our self-isolation. Lewis provides cogent arrangements and settings for voice and instrumentation, matching lyrics with traditional tunes, and also presents an illustrated YouTube lecture with sample performances of her company, Passamezzo. Her selections include the expected exhortations to repent, as well as newsy ballads, comforting Bible verses, and even satires of those fleeing the cities, spreading before us the wide assortment of responses to the end of days, since the world seems always to be ending.

Both the anonymous broadside ballad “Lord Have Mercy Upon Us” and George Withers’s hymn “For Deliverance from a Public Sickness” present us with a sinful population that begs mercy from a vengeful God. In contrast, the lovely four-part setting of “Psalm 91” assures good Christians who have mended their ways that they will be safe in God’s protection while their wicked neighbors (in an almost Brechtian Verfremdungseffekt of sweet music and bitter words) will perish:

Yea at thy side, as thou doest stand, a thousand dead shall be:

Ten thousand eke at thy right hand, and yet thou shalt be free.

John Thorne’s three-part setting of the polyphonic Latin hymn “Stella Caeli” (reputedly composed by the Portuguese Sisters of Santa Clara during the “Black Death” of 1347-1351) offers us an international connection, while Thomas Nashe’s “Litany in Time of Plague,” from his Play Summer’s Last Will and Testament (a hybrid of interlude and court masque, likely performed at Croydon Palace for Archbishop John Whitgift while London theaters were closed for the plague), brings us back to earth where “Long banished must we live from friends….” In this song, we hear (in terms reminiscent of Everyman’s memento mori), riches, beauty, health, strength, and wit all take their leaves, reminding us that the plague is the great leveler.

The broadside ballad “Christ’s Tears over Jerusalem” brings the vengeful God back specifically to London, jogging the memories of forgetful English about their recent close shave with the Spanish Armada. Nashe, in 1593 while the plague was still raging in London, published a pamphlet by the same title, with cringe-worthy lines specific to his city: “London, thou are the seeded garden of sin, the sea that sucks in all the scummy channels of the realm.”

The delightful drollery “Upon my Lord Mayor’s Day, being put off by reason of the Plague” brings us even more vividly into London’s daily life, enumerating the many pleasures of the city that the plague has forbidden: no feasting, no fireworks, no music, no parades, no plays, no pageants, no public assembly, with yet another reminder of that pesky foreign “fleet that late invaded us in eighty-eight.” Lewis ends her volume with a jaunty round: “When the Plague was in town” treats us to a four-part ditty lampooning the ministers who abandoned their flocks only to return to their churches burning in the great fire.

Collections such as this, as well as Lewis’s preceding volumes, provide vibrant snapshots of early modern life, focusing on how our ancestors celebrated, mourned, and marked all sorts of occasions in song. Her previous volumes on weddings, The Happy Couple and We’ll Wed and We’ll Bed, were particularly helpful to me as I worked my way through archives and household accounts to research the protocols of marriage in the aristocratic households of England. I could find the structures of entertainments, the costs of wedding feasts, and the occasions when guests and retainers would dance and sing, but in Lewis’s volumes I find what they sang, the actual words they would use, the customs and experiences they would invoke. Lewis’s works bring the accounts and ordinances to life, allowing us to peek into the looking glass to a time not unlike our own at people filled with the same fears and hopes we feel today.

Suzanne Westfall is a theater director, professor, and head of the Theater Department at Lafayette College. She is the author of Patrons and Performance: Early Tudor Household Revels, co-editor of Shakespeare and Theatrical Patronage, and is editing the Northumberland volume for the Records of Early English Drama.