by Jacob Jahiel

Published June 2, 2024

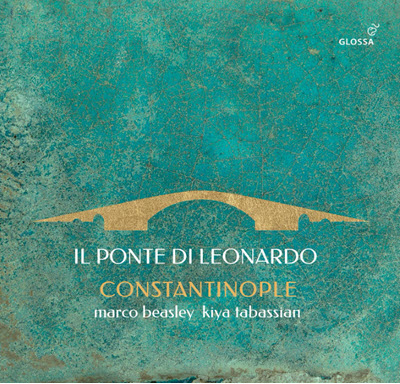

Il Ponte di Leonardo, Constantinople led by Kiya Tabassian. Glossa, GCD 924503

‘The exhilarating sense that Constantinople grasps a near-infinite array of musical possibilities is at the heart of its charm’

In 1502, Leonardo da Vinci drafted a plan for a bridge to cross Constantinople’s treacherous Bosporus Straight, bisecting what’s now Istanbul. It would have been the largest bridge in the world, connecting two continents. Although the bridge was deemed too ambitious and never built, the original architectural drawings have been preserved.

In the liner notes to Il Ponte di Leonardo, a new album by Montréal-based ensemble Constantinople, artistic director, setar player, and vocalist Kiya Tabassian quotes from Leonardo’s Prophesies:

“About the hemispheres that are infinite and are divided by infinite lines, in such a way that everyone always has one of these lines between one foot and the other. People will talk to each other, touch each other, embrace each other, from one hemisphere to another, and they will understand each other’s languages.”

Leonardo’s words, like Constantinople’s artistry, draw inspiration from two seemingly competing forces: lines of division and the connections that they paradoxically generate. It is a musical calculus of sorts — infinite cross sections that form a cohesive whole.

As a premise, building cross-cultural connections, while often illuminating, can also be fraught. Early-music practitioners, in an attempt to expand the canon, often resort to a process of mere annexation, making little effort to grapple with cultural identity of the music they play, rendering it little more than flavoring. (Too often the same ensemble presents a single tune as a Sephardic ballad or a Turkish folksong, whichever is more amenable to the theme of their program du jour.)

Il Ponte di Leonardo, however, is not that. Constantinople’s members are experts in the musical bridges they attempt to build, spanning from the Persian setar to the Turkish zither and from the viola d’amore to an amalgamation of global drumming traditions. They are joined in this project by tenor Marco Beasley, a specialist in early Italian song. Accordingly, these musicians take naturally to a repertoire that reflects the diverse and porous cultural landscape of Leonardo’s time.

The resulting soundscapes are stylistically more “early music” than strict “historical performance.” While much of the source material itself is centuries old — from 15th-century frottole to musical realizations of Rumi poems informed by long-standing traditions — Constantinople’s musicians march to the beat of their own drum (and there are plenty of drums). They rely more on the synergy of their diverse musical backgrounds than taking cues from any particular treatise — cues that, after all, might be ill-applied to much of this repertoire.

That very dynamic, the exhilarating sense that Constantinople grasps a near-infinite array of musical possibilities, is at the heart of its charm. Its richly layered instrumental textures and kaleidoscopic array of timbres are intoxicating, if occasionally a touch oversaturated. There is, moreover, a clear sense of familiarity between these musicians, creating a remarkable synchronicity and blend despite the disparate instruments and traditions they bring to the mix.

As for the singing, Tabassian’s renderings of Persian poetry form sublime, rhapsodic expressions of deep feeling. His delivery is flexible, spontaneous, and honest. Some of the early Italian offerings, however, are more uneven. Tenor Beasley glosses over key words — “foco” (“fire”) in the Tromancino; “tormento” and “lamento” in “Sera ne lo cor mio,” for instance — which are sung too casually and too coolly. Strophes sometimes fall into a monotonous sameness, and while his singsong delivery is pleasant enough, the hyper-smooth, even perfunctory delivery seems ill-suited for such passionate and vivid poetry.

The quicker, more rambunctious folkish tunes fare better and, interestingly, things improve even more in live-performance videos of the full program. Beasley’s on-stage charisma is evident, so perhaps he is simply aided by a live audience.

Nevertheless, this is an album of great imagination and ambition, offering a fantastical swirl of repertoire that, for the most part, is well delivered. Moreover, amidst a host of early-music albums that attempt to look beyond the traditional Western canon, Il Ponte di Leonardo stands out as a rare genuine expression of musical bridge building.

Jacob Jahiel is a writer, arts administrator, and viola da gamba player living in Baltimore. For EMA, he recently reviewed the brilliant duo of historical clarinetist Maryse Legault and fortepianist Gili Loftus.