by Karen Cook

Published July 20, 2020

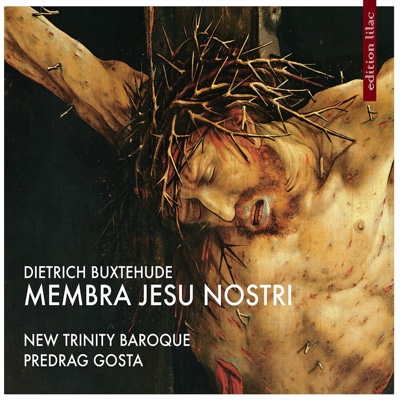

Dietrich Buxtehude: Membra Jesu nostri. New Trinity Baroque (Predrag Gosta, director). edition lilac 181109

Of the hundred or so vocal works that survive from the pen of Dietrich Buxtehude (c. 1637–1707), only one can be dated rather securely. Membra Jesu nostri was dedicated in 1680 to Gustav Düben, director of music for the King of Sweden and, like Buxtehude, a composer and organist. In his day, Buxtehude was quite renowned as a keyboard player and left behind a number of works that earned him centuries of acclaim. Attention to his vocal music, however, has only heightened over the last century, in no small part due to this particular work — just in the last few years alone, it has been recorded several dozen times.

It’s a fascinating and unusual work: Buxtehude wrote or compiled all the text himself, largely from a medieval hymn (“Salve mundi salutare”), which explains why this is his only cantata in Latin instead of the typical German. It’s not one singular cantata, but a cycle of seven interrelated cantatas, each of which describes a part of the body of the crucified Jesus (thus: feet, knees, hands, sides, breast, heart, and face). Akin to other popular portrayals of the death and burial of Jesus, the work poignantly reflects both religious ecstasy and physical sensuality through expressive text-setting: The crunchy dissonances in “Quid sunt plage iste,” gentle rocking sway of “Ad ubera portabimini,” and final meter-defying “Amen” are some of this piece’s many standout moments. But Buxtehude also carves out plenty of space for the instrumental ensemble; each cantata begins with an instrumental sonata and contains three ritornellos. The work overall is thus incredibly varied in text, texture, timbre, and affect.

It’s a fascinating and unusual work: Buxtehude wrote or compiled all the text himself, largely from a medieval hymn (“Salve mundi salutare”), which explains why this is his only cantata in Latin instead of the typical German. It’s not one singular cantata, but a cycle of seven interrelated cantatas, each of which describes a part of the body of the crucified Jesus (thus: feet, knees, hands, sides, breast, heart, and face). Akin to other popular portrayals of the death and burial of Jesus, the work poignantly reflects both religious ecstasy and physical sensuality through expressive text-setting: The crunchy dissonances in “Quid sunt plage iste,” gentle rocking sway of “Ad ubera portabimini,” and final meter-defying “Amen” are some of this piece’s many standout moments. But Buxtehude also carves out plenty of space for the instrumental ensemble; each cantata begins with an instrumental sonata and contains three ritornellos. The work overall is thus incredibly varied in text, texture, timbre, and affect.

It comes as no surprise, then, that the piece captures the hearts of so many musicians. And this 2018 addition to the fold from New Trinity Baroque is certainly full of heart. The Atlanta-based ensemble performs one on a part without benefit of a larger choir to provide the voices some respite, a choice that might foil a lesser group; these singers hold their own. So, too, does the instrumental ensemble, which performs without the separate consort of gambas required in the Sonata “Ad Cor.” The opening Sonata in tremulo in Cantata II is particularly lovely, and the full ensemble really sells individual movements like the “Surge amica mea” pair in Cantata IV.

It’s especially nice to hear the lowest voices dig into their parts with verve, and I appreciated how everyone lingers in the wrenching pathos of “Vulnerasti cor meum.” The ensemble often extends the penultimate sonority at cadences, which disrupts the momentum, as does the surprising pause at the start of “Illustra faciam tuam.” Buxtehude already provides so much variety in the overall work, and the singers’ voices are compelling enough by themselves, that I could have done without some of the extra embellishments in the solo arias. Still, the album is a solid addition to the myriad new recordings of this work, and I look forward to hearing more from New Trinity Baroque.

Karen Cook specializes in the music, theory, and notation of the late medieval and early Renaissance periods. She is assistant professor of music at the University of Hartford in Connecticut.