by Thomas May

Published April 11, 2022

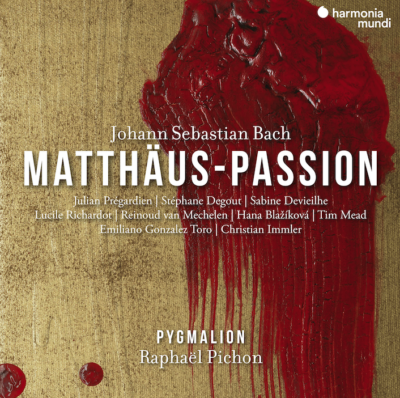

J.S. Bach’s St. Matthew Passion. Pygmalion, conducted by Raphäel Pichon. 3 CDs. Harmonia mundi HMM902691.93

Perhaps the best way to adequately describe the extremely intense, 3-D quality of motion that Raphäel Pichon and the Pygmalion ensemble achieve in the St. Matthew Passion’s opening chorus is by way of comparison with another art: say, Stendhal’s description of the young Fabrizio caught up in the fog of Napoleonic battle in The Charterhouse of Parma (which Balzac praised as a marvel that “often contains a whole book in a single page”).

Or the painful and transcendent Isenheim Altarpiece, to borrow the cross-reference suggested in the insightful interview with the conductor that is included in harmonia mundi’s hefty, trilingual booklet. Comparing “Kommt, ihr Töchter” to Grünewald’s altarpiece, Pichon remarks: “Far from presenting a monolithic, grandiose or poignant ‘overture,’ Bach plunges us straight into the very heart of a painting in motion.”

The implacable yet transparent urgency with which Pichon and his forces sweep you along leaves no question that his priority is to realize exactly what he believes Bach is aiming for: to generate an immersive, all-encompassing experience of this music. What makes this interpretation a significant contribution to the vast Matthäus-Passion discography is the admirable balance it finds between dramatic, contemplative, and even architectural approaches, too often posited as polarities.

The implacable yet transparent urgency with which Pichon and his forces sweep you along leaves no question that his priority is to realize exactly what he believes Bach is aiming for: to generate an immersive, all-encompassing experience of this music. What makes this interpretation a significant contribution to the vast Matthäus-Passion discography is the admirable balance it finds between dramatic, contemplative, and even architectural approaches, too often posited as polarities.

It took time and great care to attain this summit, nor can the intangible impact of the pandemic be ignored. The 37-year-old Pichon founded Pygmalion in 2006, and he and his excellent singers and players have systematically paved their way through a series of dramaturgical experiments focusing on rarities, such as the reconstructed Trauermusik mourning cantata Bach devoted to the memory of his pre-Leipzig boss Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen—music which incorporates parts of the St. Matthew Passion.

They waited a full decade before undertaking the Passion itself for the first time in 2016. The present recording, using the 2012 Stuttgart Bach Edition, was made in April 2021 at the Salle Pierre Boulez in the Philharmonie de Paris, directly following a live-streamed performance at the Festival de Pâques in Aix-en-Provence. Pichon uses 16 mixed voices for each of the two choirs, whose leaders divide up the solo arias as well.

Along with Pygmalion’s characterful wind solos, an especially appealing feature of the period-instrument ensemble is the variety of ever-changing timbral combinations explored with a continuo section comprising organ, cello, double bass, harpsichord, and theorbo.

The singing is of a consistently high quality, superbly balanced, and featuring the clear diction that comes from being unflaggingly invested in the meaning of each word. The choral presence persuasively evokes distinctive personalities beyond the angrily erupting turba scenes.

Julien Prégardien brings a multifaceted humanity to his role as the Evangelist. As Christus, Stéphane Degout inflects his noble delivery with intriguing hints of vulnerability—but he makes the most heart-rending impact in the final aria, “Mache dich, mein Herze, rein.” Alto Lucile Richardot is my personal favorite among the soloists, her “Erbarme dich” (along with its preceding recitative) concentrating in microcosm the singular strengths of this recording: attention to in-the-moment nuance together with a clear picture of the whole, as well as emotional involvement. All of this is achieved without mannered excess.

Soprano Sabine Devieilhe (married to Pichon) is another wonderful asset, her “Ich will dir mein Herze schenken” gracefully in sync with the way Pichon, throughout, tends to Bach’s dance rhythms to propel music and narrative. The conductor’s architectural attention to relative weights and specific articulations adds a dimension of almost sensual physicality—the emotions expressed here are vividly embodied, not abstract prayers. But in the final chorale, “Wenn ich einmal soll scheiden,” Bach’s slanting chromaticisms, delivered in naked a cappella, are made to suggest the dizzy, imminent possibility of losing control.

Throughout, Pichon walks a tightrope between historically informed suppleness and a quasi-romantic, subjective massaging of nuances—dynamic shadings, attacks, pauses. But the compelling, present-tense involvement he and Pygmalion communicate make such labeling, let alone their respective ideologies, moot. The result is a St. Matthew Passion for and of our time.

Thomas May is a writer, critic, educator, and translator. He is the English-language editor for the Lucerne Festival and contributes to the New York Times, Seattle Times, Musical America, and many other publications. He also blogs about the arts at memeteria.com.