by

Published September 24, 2018

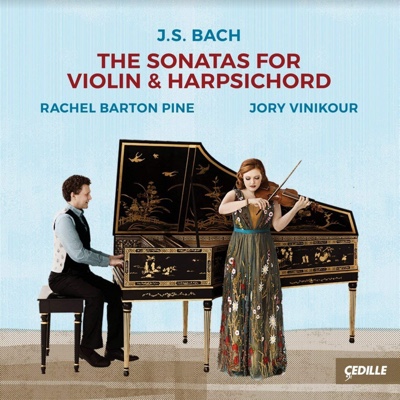

J.S. Bach: The Sonatas for Violin & Harpsichord

Rachel Barton Pine and Jory Vinikour

Cedille Records CDR 90000 177

By Daniel Hathaway

The personal friendship and professional relationship between violinist Rachel Barton Pine and harpsichordist Jory Vinikour dates back to Chicago in the late 1990s, when Vinikour returned occasionally to their mutual hometown and the two read sonatas together. “After I heard his extraordinary recording of the Goldberg Variations, I knew that we would have to record BWV 1014-1019 together someday,” Pine writes in her liner notes for their new recording on Chicago’s Cedille Records.

That someday began to take shape in 2015, when Vinikour moved back to the shores of Lake Michigan following an extended stay in Europe. After refining their interpretations over breaks between their respective concert tours, the duo recorded all six of Bach’s sonatas for violin and obbligato harpsichord in Nichols Hall at the Music Institute of Chicago over four days in September 2017. Pine plays an unaltered 1770 Nicola Gagliano violin with a replica of an 18th century bow by Louis Bégin. Vinikour brought a personal harpsichord to the sessions, an instrument inspired by a 1769 Pascal Taskin double built by Tony Chinnery in Vicchio in 2012.

That someday began to take shape in 2015, when Vinikour moved back to the shores of Lake Michigan following an extended stay in Europe. After refining their interpretations over breaks between their respective concert tours, the duo recorded all six of Bach’s sonatas for violin and obbligato harpsichord in Nichols Hall at the Music Institute of Chicago over four days in September 2017. Pine plays an unaltered 1770 Nicola Gagliano violin with a replica of an 18th century bow by Louis Bégin. Vinikour brought a personal harpsichord to the sessions, an instrument inspired by a 1769 Pascal Taskin double built by Tony Chinnery in Vicchio in 2012.

These wonderful pieces were never published during Bach’s lifetime, although they were obviously admired: They circulated widely throughout Europe in manuscript copies and, because of the expressive qualities of their sophisticated counterpoint, never went out of fashion like other Baroque works. They’re also remarkably varied in mood and texture, even though written in trio-sonata format, the harpsichordist taking the second melodic line as well as the bass.

Multiple recordings are already available of BWV 1014-1019, but this album comes with a bonus track: the Cantabile, ma un poco adagio the composer excised from Sonata No. 6 in G during one of several reworkings that make the history of that sonata rather complicated.

In the earliest manuscript of BWV 1014, copied by Johann Heinrich Bach in 1725, the sonata has six movements, of which the last merely repeats the first. Two solo movements in dance forms, for harpsichord and violin respectively, also made appearances in Bach’s E-minor keyboard Partita. Bach subsequently removed them, recasting the sonata in four movements and adding a long Cantabile, possibly an arrangement of an aria from a secular cantata.

The composer finally arrived at a five-movement version more closely related to the form of the other five sonatas, withdrawing the Cantabile altogether. Vinikour speculates in his liner notes that at 8 minutes and 22 seconds, Bach may have felt that it overbalanced the rest of the movements. It makes a fine Anhang to this disc, and although Pine doesn’t want to name a movement of the six sonatas she prefers over others, she confesses in the liner notes that “the ‘discarded’ Cantabile in G major is definitely my favorite: it’s truly the music of angels.”

It’s obvious from their excellent ensemble playing and total agreement on matters of articulation and phrasing that Pine and Vinikour have lived intimately with these pieces over an extended period of time and given ample thought to interpretative decisions.

Even in the HIP era, Bach performances cover a spectrum of styles and tastes from the austere to the ornate. Pine’s playing here leans toward the spartan. She uses vibrato with great restraint, though some long notes could use a bit of warmth, and she prefers short phrases. Pauses before bar lines and points of harmonic inflection sometimes sound mannered. Vinikour, consistently elegant, is the consummate collaborator.

With this disc, Pine and Vinikour have made a valuable addition to the list of complete recordings of these sonatas. Finely-nuanced and vibrantly captured by Cedille’s production team of James Ginsburg, Bill Maylone, and Jeanne Velonis, these performances will generously repay repeated, careful listening.

Daniel Hathaway founded ClevelandClassical.com after three decades as music director at Cleveland’s Trinity Cathedral. He studied historical musicology at Harvard College and Princeton University, and orchestral conducting at Tanglewood, and team-teaches Music Criticism at the Oberlin Conservatory of Music.