by

Published November 19, 2018

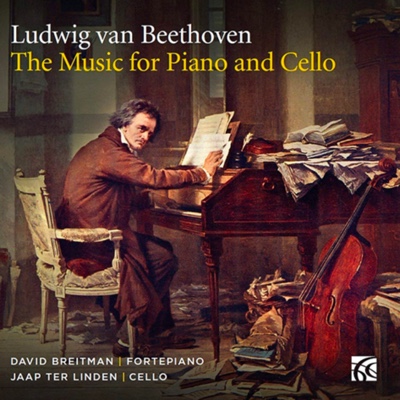

Beethoven: The Music for Piano and Cello

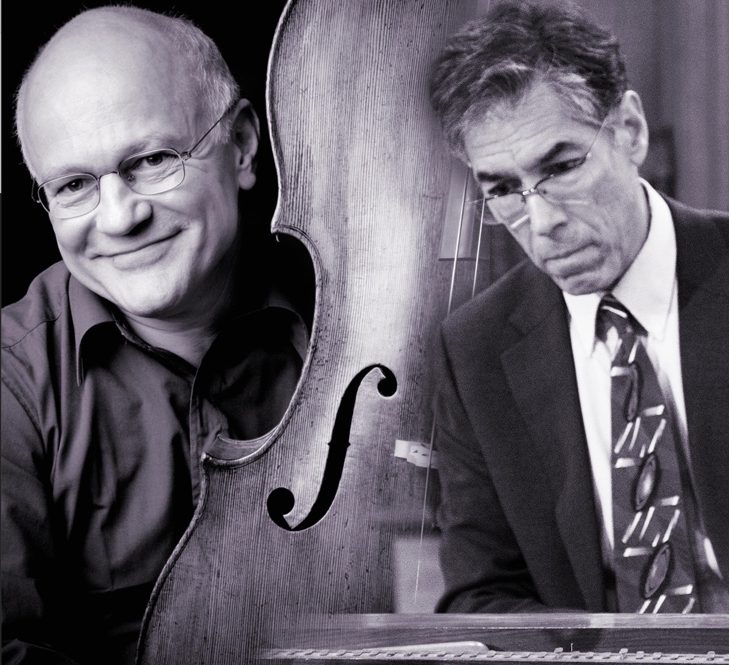

David Breitman, fortepiano, and Jaap ter Linden, cello

Nimbus NI 6362

By Andrew J. Sammut

Mark Kaplan’s chapter on Beethoven’s chamber music in The Cambridge Companion to Beethoven notes that, by the time of the composer’s third of his five cello sonatas, “greater compositional technique allowed Beethoven the possibility of using fewer notes with confidence.” This idea of the power of restraint came to mind listening to fortepianist David Breitman and cellist Jaap ter Linden throughout this complete collection of Beethoven’s music for piano and cello.

The third statement of the opening movement of that third sonata follows a light piano cadenza and enters on a minor chord, immediately swerving into darker territory. Breitman and ter Linden underline the tension of this moment without melodrama or dynamic hairpins; an excuse for excess becomes all the more effective for its self-control. This is more than a matter of “letting the music speak for itself.” Both musicians add their own organic phrasing: ter Linden can go from lyrical to driving on a dime and Breitman’s muscular articulation makes even double-dotted notes crackle in place. Their interpretation is vivid and deliberate, yet the pair ease into and lay back from the score and each other in a way that lets the listener feel but not necessarily hear them at work.

The third statement of the opening movement of that third sonata follows a light piano cadenza and enters on a minor chord, immediately swerving into darker territory. Breitman and ter Linden underline the tension of this moment without melodrama or dynamic hairpins; an excuse for excess becomes all the more effective for its self-control. This is more than a matter of “letting the music speak for itself.” Both musicians add their own organic phrasing: ter Linden can go from lyrical to driving on a dime and Breitman’s muscular articulation makes even double-dotted notes crackle in place. Their interpretation is vivid and deliberate, yet the pair ease into and lay back from the score and each other in a way that lets the listener feel but not necessarily hear them at work.

The second movement of the second sonata is beautifully paced from the outset so that the forte comes as an exclamatory release rather than a calculated effect. The brooding fourth variation of the “Variations for Cello and Piano on Mozart’s ‘Bei Männern’” stays rhythmically buoyant and focused, creating a natural progression between the delicate preceding movement and the playful dialog following it. The sheer joy Breitman and ter Linden describe in the liner notes about getting to play this music with each other is also on display throughout the album. The fifth sonata’s opening Allegro alternates between earnest, song-like themes, dancing rhythms and surging passagi (as well as humorous, well-timed pizzicato bumps). Harmonically probing moments such as those of the first sonata’s Allegro come across as explorations, the duo performing with genuine curiosity about where Beethoven is headed, even if they may have already played his works countless times.

Breitman and ter Linden have also expressed excitement about the opportunity to cover Beethoven’s entire catalog for piano and cello on period instruments. Breitman’s comments in the liner notes emphasize how the right instruments allow fidelity to Beethoven’s dynamic markings while maintaining proper balance. Unsurprisingly, his choice of instruments here proves illuminating. He alternates between Philip Belt’s copy of an Anton Walter fortepiano from circa 1800 and Paul McNulty’s copy of a model by Conrad Graf from 1819. Both keyboards are bright but resonant across all registers, with bass notes displaying an attractive grain that never simply “booms” into a blur. Linden’s 1799 cello by Johannes Cuypers (a.k.a. “The Dutch Stradivari”) gives an agile, warm voice to all of these musical roles while remaining relentlessly beautiful.

Above all, the imagination Beethoven displays in these eight works for two instruments comes across as an organic and personal biography. Music historians describe a progression from the lyrical and piano-centric first two sonatas from 1796, through the cello and piano being placed on virtuosic equal footing in the third sonata from circa 1807, and up to the more experimental and dramatic last two sonatas. Yet all of these works, as well as the “lighter” three sets of variations on arias by Handel and Mozart, exploit a range of structural, harmonic, emotive, dynamic and textural ideas. Breitman and ter Linden’s poised, flexible playing and musicianship offer it all up as narrative, not musicology. Clear acoustics and engineering at Oberlin Conservatory of Music’s Clonick Hall provide an ideal vehicle for it all.

Andrew J. Sammut has written about early music and traditional jazz for Early Music America, The Boston Musical Intelligencer, All About Jazz and his own blog. He lives in Cambridge, MA.