by

Published May 20, 2019

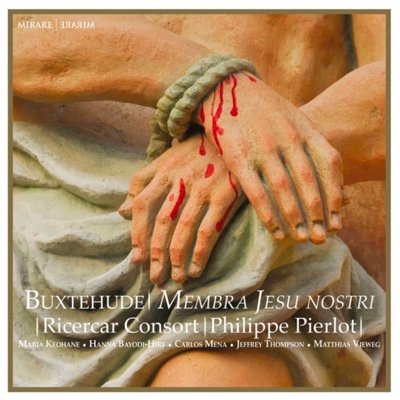

Dietrich Buxtehude: Membra Jesu nostri

Ricercar Consort (Philippe Pierlot, director)

Mirare MIR444

By Karen Cook

Over the past four decades, the Ricercar Consort has proven to be a formidable force in early-music performance whose reputation was founded on German Baroque music. It stands to reason, then, that the Belgian ensemble’s new recording of Buxtehude cantatas would continue their legacy of excellence — and it does.

Dietrich (or Dieterich) Buxtehude (c. 1637–1707) has until relatively recently been best known for his keyboard works. He was a very well-known organist in his day, and the legend persists that Johann Sebastian Bach himself once traveled for over three hundred kilometers to hear him play. But Buxtehude was also a prominent and influential composer of vocal works, and more than 100 such compositions survive, a fact to be celebrated given that so many of his pieces were lost. Of all these vocal works, only one is dated by Buxtehude himself: The cycle of seven cantatas collectively called Membra Jesu nostri was dedicated to Gustav Düben, an organist, composer, and director of music to the King of Sweden, in 1680.

Dietrich (or Dieterich) Buxtehude (c. 1637–1707) has until relatively recently been best known for his keyboard works. He was a very well-known organist in his day, and the legend persists that Johann Sebastian Bach himself once traveled for over three hundred kilometers to hear him play. But Buxtehude was also a prominent and influential composer of vocal works, and more than 100 such compositions survive, a fact to be celebrated given that so many of his pieces were lost. Of all these vocal works, only one is dated by Buxtehude himself: The cycle of seven cantatas collectively called Membra Jesu nostri was dedicated to Gustav Düben, an organist, composer, and director of music to the King of Sweden, in 1680.

The fact that it is dated is not the only thing that sets this work apart. While the rest of Buxtehude’s cantatas adhered to the Lutheran style of setting sacred works in German, Membra Jesu nostri is entirely in Latin — not a marker of Catholicism, but rather of the kind of musical erudition Buxtehude saw in Düben. Buxtehude wrote or compiled its text himself, largely from the Medieval hymn “Salve mundi salutare.” The text of this hymn is divided into seven parts, and thus the work itself is divided into seven self-contained cantatas, each describing a different section of the crucified body of Jesus. In this respect, the piece is a musical counterpart to Martin Luther’s sermons on the Passion of Christ, which emphasized both its ecstasy and its anguish.

So does the Consort. They show off their exquisite blend in movements such as the intimate, tortured “Vulnerasti cor meum,” the gorgeously intense concerto “Quid sunt plagae istae,” or the rocking lilt of “Salve, caput cruentatum,” but also their great precision in the agitated off-beat accents of the concluding Amen. The much shorter concluding cantata Gott, hilf mir also gives them a chance to show off their more urgent side, over and against the pathos of the longer first work. If there were such a thing as a drawback here, it would be that the violas da gamba are so sparingly called for by Buxtehude that we only get to hear them in the “Ad cor” cantata.

Having performed the piece myself, there are moments in which their decisions on tempo or phrasing differ from what lives in my mind’s ear, but their choices are effective, suiting well both the works themselves and the particular construction of their ensemble. Vocalists and instrumentalists (and director) alike are to be commended for such a beautifully transparent, luminous performance, which certainly earns a high place in the field of Buxtehude recordings.

Karen Cook specializes in the music, theory, and notation of the late medieval and early Renaissance periods. She is assistant professor of music at the University of Hartford in Connecticut.