by Andrew J. Sammut

Published June 20, 2022

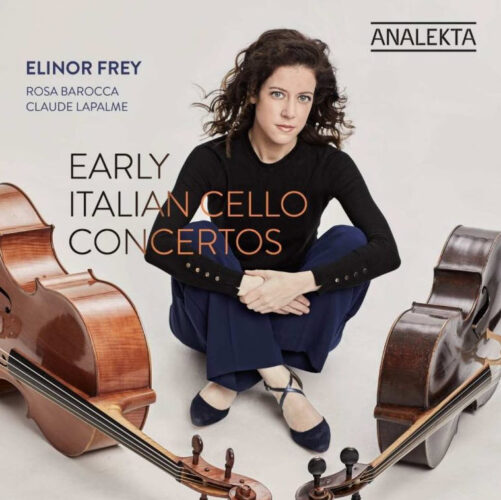

Early Italian Cello Concertos. Elinor Frey, cello, with Rosa Barocca directed by Claude Lapalme. Analekta AN29163.

After mainly recording sonatas with continuo, Early Italian Cello Concertos is Frey’s first release focused on that genre. She partners with the period-instrument ensemble Rosa Barocca and their artistic director, Claude Lapalme. Founded in 2016, the Alberta-based collective of Canadian and U.S. musicians specializes in historically informed performance. This CD with Frey is the group’s first recording.

Virtuosity abounds in these concertos: high notes, fast runs, and techniques such as bariolage in Giovanni Battista Sammartini’s Concerto in C Major. And there’s plenty of Italian lyricism. But there are also novel compositional touches—like Leonardo Leo’s five-movement Concerto No. 2 in D Major demonstrating both his theatrical and polyphonic styles or the brooding minor-key Largo in Antonio Vivaldi’s otherwise exuberant Concerto in G Major (RV 414). The soloist’s transcriptions of slow minor key movements from Giuseppe Tartini’s Sonate Piccole for violin and continuo add further variety.

Frey highlights these works’ expressiveness as well as their beauty and fireworks. Her sense of unity and proportion add flow to the highly ornamented Larghetto of Tartini’s Concerto in A Major (GT 1.A28). She joins the first movement of the Leo concerto in measured, noble flourishes like an opera seria protagonist coming onstage for their entrance aria. Moving double-stops and bass notes heighten the melancholy in the Andante Cantabile from Tartini’s Violin Sonata No. 6 in E Minor (B.e1).

Clear tone and subtle articulation maintain the arc of individual phrases in faster movements; Frey says something even as she executes impressive feats. Oscillating lines in the closing Allegro of the Vivaldi, for example, leap in with character as well as momentum. She adds a smooth sound with lots of rich harmonics to the syncopated Allegro of Tartini’s concerto. The bright color and slight swagger in Sammartini’s concerto show she enjoys this music and this instrument.

For the Sammartini concerto and Tartini’s works, Frey performs on a cello that is ¾ the size of a modern instrument (made in 1770 by German luthier Matthäus Friedrich Scheinlein). Pitched one octave below the violin with a glistening tenor register, Frey describes this instrument as well-suited for fast passages and upper-register phrases. For the Vivaldi and Leo pieces, Frey uses the more common variety of cello (built by Karl Dennis of Rhode Island, after a 1708 Stradivarius). This larger, slightly darker instrument stays pliant in Frey’s hands, for example, in the skipping Con Bravura of the Leo concerto. It also creates unique textures alongside the orchestra’s strings.

Rosa Barocca’s tight, responsive playing adds color and spark. They shine in orchestral spots like the robust introduction to Sammartini’s concerto and the truly “grazioso” curling figures in Leo’s music. Lapalme’s well-judged tempos and nuanced direction find the sweet spot between refinement and fire. The orchestra becomes an engaging accompanist (rather than background or filler). Sensitive dynamics and balance between voices also bring clarity to sections like Leo’s shimmering and rhythmic fugue.

Rosa Barocca and director Lapalme are wonderful partners for another example of Elinor Frey’s inventive, assured, and expressive advocacy for “new” 18th-century music. A soft acoustic inside the University of Calgary’s Rozsa Centre, clear audio, and Frey’s informative liner notes round out an already enjoyable album.

Andrew J. Sammut writes about classical music and jazz for All About Jazz, The Boston Classical Review, The Boston Musical Intelligencer, Early Music America, The Syncopated Times, and his blog. He also works as a freelance copy editor and content writer.