by Jarrett Hoffman

Published January 4, 2021

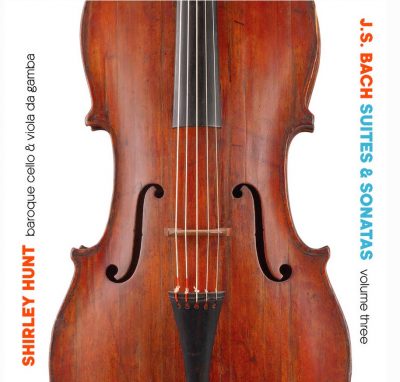

J.S. Bach Suites & Sonatas, Vol. 3. Shirley Hunt, cello and viola da gamba; Ian Pritchard, harpsichord. Letterbox Arts.

If some higher being stepped down from the sky, called a press conference, and revealed exactly which instrument J.S. Bach had in mind for his challenging and high-register-heavy Cello Suite No. 6, it would of course be confusing for the majority of people on the planet. But it would be cause for celebration among many musicologists and musicians. No more puzzling over the number of strings for which Bach was writing — likely a fifth upper string — or whether he instead was thinking of a separate instrument entirely, a relative of the cello known as the violoncello piccolo.

Given that hypothetical scenario, here’s another valid reaction: mixed feelings. That’s because all the mystery surrounding the piece has resulted in a beautiful diversity of compelling interpretations, the latest from Boston-based Shirley Hunt.

Given that hypothetical scenario, here’s another valid reaction: mixed feelings. That’s because all the mystery surrounding the piece has resulted in a beautiful diversity of compelling interpretations, the latest from Boston-based Shirley Hunt.

On J.S. Bach Suites & Sonatas, Vol. 3, Hunt performs that final suite using a rare creature: an 18th-century, five-stringed cello still in playing condition. Built by Marcus Snoeck in 1720 (around the time the suites were written) and housed at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, the instrument here makes its studio recording debut. The disc continues in the key of D Major with the Second Gamba Sonata and finishes with the Third Cello Suite in C Major as Hunt closes the book on her impressive survey of Bach’s contributions to those two genres.

Hunt’s performances throughout the album are technically strong and interpretively absorbing. One aspect of her playing that stands out is her judicious use of rubato, maintaining the flow of the music while creating some particularly satisfying moments, like the final stretch of the Prelude in the Sixth Suite. Adding to the experience is the intimate nature of the recording, engineered and mastered by Vince Go. The occasional sounds of breath moving and fingers working add a special vibrancy without becoming distracting.

As for the Snoeck instrument, its earthy, grainy tone charms more and more as the Sixth Suite progresses, from that life-affirming Prelude to the boundless energy of the Gigue. The fifth string doesn’t suddenly make the music sound easier — things still get tense, even a little strained, as per usual with this singular piece. That might be disappointing for those hoping for a magic fix, but for others maintains the work’s appeal.

The Third Suite introduces Hunt’s own 18th-century cello by William Forster, Sr. — more robust and velvety but with a grit that matches the Snoeck well. And in between the suites, we hear contemporary reconstructions of old instruments in the gamba sonata, in which Hunt is joined by harpsichordist Ian Pritchard. The sonata brings a refreshing contrast of sound and style, due both to the leaner and focused sound of the gamba and the harpsichord and the humbler atmosphere of the piece, especially compared to the epic suites.

But in one way, the contrast goes too far. In great performances like those on this disc, the suites conjure a remarkable sense of wide-open space that can even feel healing, as cliché as that is. But the second and fourth movements of the sonata counteract that effect with near-constant motion in both parts. Even as Hunt and Pritchard bring impressive agility and character to those long streams of notes, the result is claustrophobic.

Still, a curatorial complaint like that doesn’t take away from the historical and artistic achievement represented by this set of recordings, now complete.

Jarrett Hoffman is the managing editor at ClevelandClassical.com and served as a fellow at the 2014 Rubin Institute for Music Criticism. As a clarinetist, he performs in the Hudson Valley and New York City and runs a private studio.