by

Published January 14, 2019

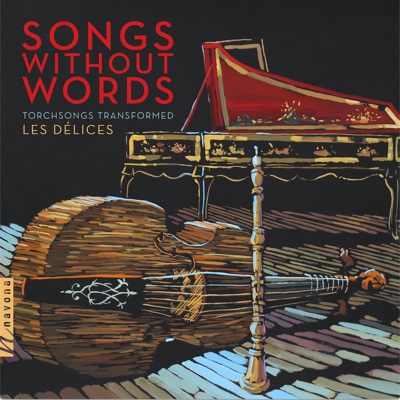

Songs Without Words

Les Délices

Navona NV 6195

By Andrew J. Sammut

The Cleveland-based chamber ensemble Les Délices finds ample common ground between French Baroque airs and modern popular standards on Songs Without Words. The material shares a penchant for bittersweet melodies and piquant harmonies, so Marais’ Prelude In A Minor (from the fourth suite of the Quatrième Livre) feels like a tense meditation after Johnny Mandel’s earnest 1964 love song “Emily.” The musicians’ spacious and expressive arrangements also bridge each period’s sensibilities. “Tristes Apprêts” from Rameau’s Castor Et Pollux reflects on losing a friend with the directness of a song on the radio. “Tomorrow Is My Turn” was written by Charles Aznavour, France’s Sinatra, in 1962. Here, its prediction of better days ahead unfolds as a courtly dance in triple meter that adds to the underlying doubt.

Lyrics are not included but would have been superfluous. The meaning of Lambert’s “D’en feu secret” (“From a Secret Fire”) is clear enough in Mélisande Corriveau’s palpitating viola da gamba and Debra Nagy’s hushed oboe. A cool reading of Billy Strayhorn’s “A Flower Is A Lovesome Thing” conveys loneliness amid beauty. The torch-song element alluded to in the disc’s subtitle is sometimes obvious in the songs themselves, at other times subtle, as in the slow burn on The Beatles’s “Michelle” and Erroll Garner’s “Misty.” The trio’s blend occasionally resembles the wash of an accordion. Eric Milnes’ harpsichord also adds understated percussive colors in the right spots like a tasteful jazz drummer.

Lyrics are not included but would have been superfluous. The meaning of Lambert’s “D’en feu secret” (“From a Secret Fire”) is clear enough in Mélisande Corriveau’s palpitating viola da gamba and Debra Nagy’s hushed oboe. A cool reading of Billy Strayhorn’s “A Flower Is A Lovesome Thing” conveys loneliness amid beauty. The torch-song element alluded to in the disc’s subtitle is sometimes obvious in the songs themselves, at other times subtle, as in the slow burn on The Beatles’s “Michelle” and Erroll Garner’s “Misty.” The trio’s blend occasionally resembles the wash of an accordion. Eric Milnes’ harpsichord also adds understated percussive colors in the right spots like a tasteful jazz drummer.

Les Délices captures an ideal balance between French restraint and earnest American sentiment. Yet when the trio opens up, for example in the Peruvian waltz “La foule” made famous by Edith Piaf, the results are rhythmically infectious yet never frivolous. “Crazy,” the jazzy pop ballad written by Willie Nelson and made famous by Patsy Cline, features Corriveau slapping her gamba, Milnes strumming the keys, and Nagy catching the drawl and lilt of a country singer.

Downright impressive playing underpins all the emotion and energy. Nagy’s oboe is strong and nuanced, clearly enunciating Hotteterre’s ornate flute transcription of Bousset’s “Des mes soupirs.” Corriveau also shows microscopic attention to detail and meticulous yet natural phrasing crucial to this repertoire. Yet they can both just plain belt out a tune, for example Nagy’s bell-like upper register on Lambert’s “Vos méspris chaques jour” or Corriveau’s tonal and rhythmic play on “Misty.” Corriveau also plays a violin-like lead on pardessus de viole in Joseph Chabanceau de la Barre’s “Allez Bergers.” Milnes’ harpsichord provides a lush texture throughout the album. The recording captures the instrument’s big sound and Milnes rich voicings — both in accompaniments and “comping” — from Clonick Hall at the Oberlin Conservatory of Music in Ohio.

The clearest link between these periods/styles is the emphasis on improvisation, spontaneity, and treating the composer’s music as a springboard to the musicians’ realization. Baroque ornamentation comes across as on-the-spot embellishment, as in Marais’ La Folía variations, and ensemble improvisation sounds like orchestration, for example the gamba sliding under the oboe’s vocalizations like the string section of a dance orchestra on “Emily.”

Jam-session warhorse “Autumn Leaves” closes the album with Corriveau walking a bass viol and Milnes adding spare chords under Nagy’s bebop lines. It’s the most overtly jazz-influenced track and, at less than two minutes, enough of a glimpse into how other groups might have approached this project. Rather than simply playing jazz on period instruments or Baroque interpretations of popular music, Songs Without Words is an inventive and warm performance of what Duke Ellington astutely called “good music.”

Andrew J. Sammut has written about early music and traditional jazz for All About Jazz, Boston Classical Review, The Boston Musical Intelligencer, Early Music America, the IAJRC Journal, and his blog, The Pop of Yestercentury. He has also written and copy-edited liner notes for independently-produced historical reissues of jazz from the twenties.