by Karen Cook

Published November 29, 2021

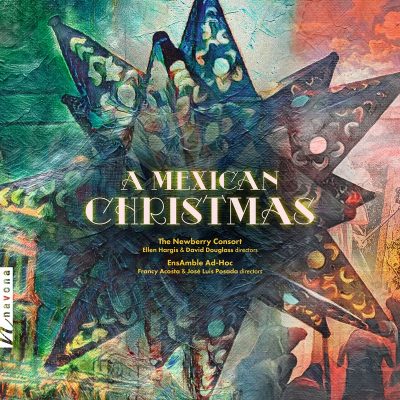

A Mexican Christmas. The Newberry Consort and EnsAmble Ad-Hoc. Navona NV6375.

In 17th-century Mexico, the Christmas season was boisterous and lively, a time as much of rejoicing as of sacred wonder, and convents were central to these celebrations. In these past Christmas celebrations, music would happen both within and outside the convents, from the nuns’ solemn musical worship to the villancico bands that gathered outside the cloister walls.

On this latest album, a joint effort from the renowned Chicago-based Newberry Consort and Colombian newcomers EnsAmble Ad-Hoc, listeners are treated to a modern rendition of this historical soundscape. The two groups alternate between sacred plainchant, motets, and “learned” villancicos appropriate for liturgical worship on the one hand and a variety of secular genres with a full complement of colonial and Mexican traditional instruments on the other.

On this latest album, a joint effort from the renowned Chicago-based Newberry Consort and Colombian newcomers EnsAmble Ad-Hoc, listeners are treated to a modern rendition of this historical soundscape. The two groups alternate between sacred plainchant, motets, and “learned” villancicos appropriate for liturgical worship on the one hand and a variety of secular genres with a full complement of colonial and Mexican traditional instruments on the other.

The album, recorded live in 2019, opens with a raucous mélange of sounds that quickly settle into a joyful street villancico, filled with hand claps and foot stomps, violin, and a host of descendants of the Spanish guitar. But this exuberance is quickly interrupted by the serene voices of the Newberry Consort’s female choir, who represent the nuns by singing Juan Gutiérrez de Padilla’s motet Christus natus est nobis. The beautiful “Voces, las de la capilla” (also by Gutiérrez de Padilla) follows, chock full of musical symbolism and puns of which the original singers must certainly have been aware.

From there, the album alternates between similar liturgical works for inside the convent — and of these, Joan Cererols Montserrat’s “Suspended, Cielos, vuestro dulce canto” is a real standout for its superb build toward the final cadence — and groups of lively songs for the streets. These include villancicos, ensaladillas, and a baile, or dance, but also guineos and negritos, genres of songs that reflect the mix of Spanish, African, and indigenous heritage present in 17th-century Mexico. For example, another musical highlight is Gaspar Fernandez’s “Dame albriçias, mano Antón,” whose fascinating rhythmic and harmonic shifts underpin a dialogue between people of African descent rejoicing to hear that Jesus was born in Guinea. Two shorter instrumental works by Santiago de Murcia (“Cumbé” and “La Azucena”) let the villancico ensemble really dig into some of the exciting rhythmic vitality featured in this repertory. The album concludes with Juan García de Zéspedes’s “Convidando está la noche,” the ensembles combining to let their hair down in an exuberant dance.

The album is, in a word, fun. It’s easy to hear that both ensembles are enjoying themselves, as is the audience, which claps and cheers enthusiastically. As a live recording, the ambience occasionally muffles the clarity of the text, and my only frustration is that I have yet to locate the texts and translations* for the vocal works, which I hope is my own error — it would be a surprising omission, given how little known many of these pieces are. Overall, though, it’s an enjoyable, exciting photograph of a Christmas season gone by.

Karen Cook specializes in the music, theory, and notation of the late medieval and early Renaissance periods. She is assistant professor of music at the University of Hartford in Connecticut.

*Update, 12/1/21: Details about the recording, including the texts and translations, are now available on the Navona Records website.