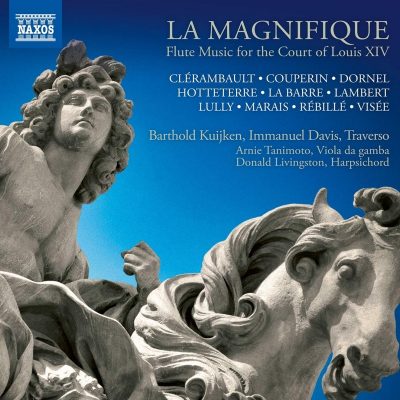

La Magnifique: Flute Music for the Court of Louis XIV. Barthold Kuijken, Immanuel Davis, transverse flutes; Arnie Tanimoto, viola da gamba; Donald Livingston, harpsichord. NAXOS 8.579083

It’s fun to think about the fashionable members of Louis XIV’s court as early adopters of the latest technological device — only instead of an iPhone, it was the flute. Flutes, of course, have long and well-documented histories. But as with other woodwind instruments, the flute went through a transformation in the 17th century. It began to be built in three sections, with a conical bore and a single key, allowing it to better navigate chromatic music and have a wider dynamic range and more flexible tone.

This new “Baroque” flute first started to catch on at Louis’s court, especially at first to imitate or replace the voice or to perform gentle airs on ideas of love. Later on, composers began to explore the possibilities of the flute as an instrument unto itself, and thus flute sonatas and suites began to proliferate. As flutists Immanuel Davis and Barthold Kuijken point out in the liner notes of their new recording, none of these are sweepingly Romantic, exhibitionist pieces, for in French society, decorum ruled and emotions were never displayed but carefully restrained. Louis was apparently quite enamored of the new instrument, holding regular concerts in his private chamber, and a number of the works on this new album might well have been performed at just such occasions.

This new “Baroque” flute first started to catch on at Louis’s court, especially at first to imitate or replace the voice or to perform gentle airs on ideas of love. Later on, composers began to explore the possibilities of the flute as an instrument unto itself, and thus flute sonatas and suites began to proliferate. As flutists Immanuel Davis and Barthold Kuijken point out in the liner notes of their new recording, none of these are sweepingly Romantic, exhibitionist pieces, for in French society, decorum ruled and emotions were never displayed but carefully restrained. Louis was apparently quite enamored of the new instrument, holding regular concerts in his private chamber, and a number of the works on this new album might well have been performed at just such occasions.

The recording walks the listener through this progression in flute performance and composition at the French court, beginning with some of the earliest music composed for the new Baroque flute: Jean-Baptiste Lully’s 1681 “Ritournelle pour Diane” from Le Triomphe de l’Amour. The listener is also treated to some of those delicate airs, here from Michel Lambert, Jacques Hotteterre, and François Couperin. Excerpts from flute suites by Philbert Rébillé, Louis-Antoine Dornel, and Robert de Visée mark the next stage of flute composition, which reaches its height in the full sonatas, suites, and concertos included by Hottetterre, Couperin, Michel de La Barre, and Marin Marais.

The disc kicks off with a lengthy Simphonia by Louis-Nicolas Clérambault. Some of these names are much more widely known than others, so it is exciting to note that this is the world premiere recording of Lambert’s two airs, Rébillé’s menuet, and de Visée’s sarabande; no less exciting, though perhaps more surprising, is that the same can be said for Lully’s “Ritournelle,” Hotteterre’s excerpt from his Recueil d’airs sérieux et à boire, and Couperin’s excerpt from a publication of the same name. What is more, Couperin’s Concert No. 13 in G major was written for any two same-ranged instruments; this version for two flutes also receives its world premiere recording here. For such a list of French warhorses, this is an astonishingly new amount of repertoire to hear for the first time.

The ensemble performs everything delightfully. For all their emotional reserve, these works are charming, graceful, and sensitive, the musical equivalent of a carefully displayed ankle, a subtle turn of the wrist, a glimpse of an eye behind a lacy fan. The historically informed instruments have the warmth and gentle rasp of wood, their timbres interweaving so well that it’s impossible in places to tell the two flutists apart. Special praise goes to the acoustical space and miking that allow the listener to hear the wide variety of articulations used by the performers (listen in particular to Rébillé’s Menuet). These are well-described in treatises of the time, thus linking the performance choices made today to those documented in the past, and also to the desire for this kind of music to emulate vocal song and even elegant conversation. It’s an album that rewards at first hearing, and even more so upon repeat listening.

Karen Cook specializes in the music, theory, and notation of the late medieval and early Renaissance periods. She is assistant professor of music at the University of Hartford in Connecticut.