by Aaron Keebaugh

Published August 3, 2020

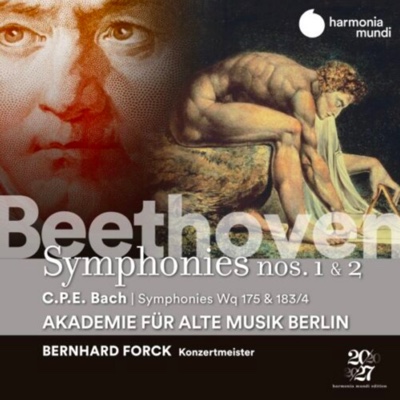

Beethoven: Symphonies Nos. 1 and 2; C. P. E. Bach: Symphonies in F major and G major. Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin. harmonia mundi HMM 902420

Hearing Beethoven’s symphonies on period instruments can reveal the freshness of the composer’s original conceptions. That is the sense conveyed by the Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin, which offers Beethoven’s first two symphonies on a new recording from harmonia mundi. Crisp and teeming with vitality, the readings suggest that these familiar works, often seen as transitional, are in fact true experiments in form.

Made to celebrate the composer’s 250th birthday in 2020, the recording is part of a multi-year, multi-ensemble project to release new versions of Beethoven’s complete symphonies. The Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin has so far released a colorful rendering of the Symphony No. 6 on the label, and it will follow with the Fourth and Eighth Symphonies next year.

Made to celebrate the composer’s 250th birthday in 2020, the recording is part of a multi-year, multi-ensemble project to release new versions of Beethoven’s complete symphonies. The Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin has so far released a colorful rendering of the Symphony No. 6 on the label, and it will follow with the Fourth and Eighth Symphonies next year.

Led by concertmaster Bernhard Forck, the ensemble plays with a laudable cohesion that allows for the intricate details in these works to emerge. In their hands, the Symphony No. 1 takes on an unfamiliar dramatic weight. The orchestra carefully maneuvers between the contrasting interplay of strings and winds in the first movement while carrying the tension to the final resolution. The minuet, under a brisk tempo, contains all the power and punch of Beethoven’s later scherzos. The musicians push the momentum forward in the finale, where witty lines swell into grand statements by the end. There are other moments to savor, particularly in the opening lines of the Andante, that flower in the ensemble’s middle strings.

Beethoven’s Symphony No. 2 is more daring on paper as the composer expanded the form in several movements. The Akademie für Alte Musik unveils all of its pent-up energy while also finding the work’s humor. The bassoon passages in the finale offer an especially light moment, recalling the clucking of hens in Haydn’s Symphony No. 83 (“La Poule”). The Scherzo offers an ear-tickling play on shifting dynamics and textures.

There are lovely lyrical moments here as well. The passages traded between the strings and winds in the Allegro’s second theme reveal Beethoven’s gifts as a melodist. The Larghetto, with its rising and falling gestures, is likewise an essay in utmost sensitivity.

Beethoven’s early symphonies are obviously in the vanguard when compared with the music composed in prior decades. To amplify the comparison, this disc includes two short symphonies by Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach.

Bach, fifth son of Johann Sebastian and Maria Barbara, possessed a voice capable of wide expressive possibilities, if not technical daring. As performed by the Akademie, the three movements of the Symphony in F major, Wq. 175, course with intensity. Strings dominate much of the texture in the outer movements, though the orchestra’s superb winds establish warm contrasts. The Andante takes on the freedom of a recitative — a principal element of Bach’s style — the line rising, twisting into arcs, and falling away.

The Symphony in G major, Wq. 183/4, dates to the mid-1770s, the most prolific period of Bach’s life, and showcases the joy and emotional tension of the composer’s style. The Akademie musicians traverse the first movement’s surprising key changes, using dynamic shading to further highlight such far-away tonalities as C-sharp major and F-sharp minor. The finale takes on a terpsichorean flair, while the Poco andante again moves with an improvisational freedom. Bach, as relayed here by Forck and the Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin, pushed musical boundaries in his own way.

Aaron Keebaugh has written for The Musical Times, Corymbus, and The Classical Review, for which he serves as Boston critic. A musicologist, he has taught courses in music and history at North Shore Community College in Danvers, MA.