by Aaron Keebaugh

Published September 6, 2021

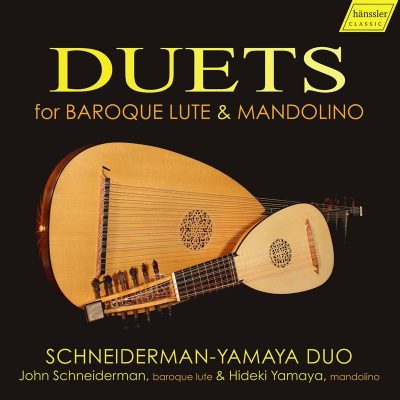

Duets for Baroque Lute and Mandolino. John Schneiderman, baroque lute, and Hideki Yamaya, mandolino. Hänssler Classic HC21006

In the early 18th century, the lute was enjoying a second golden age. Though it was no longer the instrument of choice for monarchs around Europe, music for the lute flourished in Germany and the Eastern countries, and many composers adapted styles from earlier Italian models.

But the baroque lute never seems to have caught on in Italy. In fact, there is no evidence that the 11- to 13-course instrument, invented in the early 1600s, had ever been played alongside its Italian cousin, the mandolino, despite music for the smaller instrument surviving in Berlin, Vienna, and Prague.

But the baroque lute never seems to have caught on in Italy. In fact, there is no evidence that the 11- to 13-course instrument, invented in the early 1600s, had ever been played alongside its Italian cousin, the mandolino, despite music for the smaller instrument surviving in Berlin, Vienna, and Prague.

Lutenist John Schneiderman and mandolinist Hideki Yamaya are making a case for this combination in Duets for Baroque Lute and Mandolino, released on the Hänssler Classics label. By turns joyful and stately, the album reveals this pairing to be a natural fit.

Three works on the recording were composed by Ernst Gottlieb Baron (1696-1760), perhaps the best-known lutenist of the late Baroque era. A familiar figure in the court of Frederick the Great, Baron composed mainly for the lute, amassing a considerable corpus of suites, fantasias, partitas, and concertos.

His two concertos in D minor, heard on this recording, showcase technical prowess and wide emotional contrasts. The melancholic Adagio and the ensuing bright-toned Allegro in the first concerto (originally for recorder and lute) bring Corelli to mind. Schneiderman and Yamaya engage in gentle melodic dialogue in the Siciliana to release the tension momentarily. The closing Gigue, with its angular melodies, tips the music once again towards darkness.

Baron’s second concerto reveals the composer’s interest in counterpoint. Schneiderman and Yamaya handle the quicksilver lines of the Allegro with the ease of friendly dialogue. In the Vivace, the two instruments are also equal partners, particularly in passages where they spin a constant rhythm over a harmonic vamp to create an orchestral effect. Schneiderman and Yamaya play this movement with urgency. But the Largo, originally scored for violin and lute, is the heart of the work, a scene of sweet melancholy in the duo’s sensitive reading.

Schneiderman and Yamaya make Baron’s Duetto in G major into a sonata in all but name. They trade lines gracefully in the Allegro to capture a dance quality. That sense of motion carries into the improvisatory Adagio before the duo heightens the tension in the concluding Presto.

The other concerto on this recording is by Blohm, a composer from the 18th century whose biography has been lost to history. His Concerto in C major, originally for violin and lute, flips expectations, as the lute is given the lead role.

The buoyant Allegro features Schneiderman and Yamaya in bright musical conversation, trading lines with assurance. A sense of joy marks the Menuet, with brief shifts to the minor key in the trio bringing hints of gloom. Here too, the middle movement — a Siciliano — is the gem of the setting, where the duo craft their phrases in long arcs.

Corelli’s influence can also be heard in Bernhard Joachim Hagen’s Duetto in C minor, here played with panache and expressivity. The work offers a contrapuntal display for each musician. Schneiderman performs with a zest and energy that is finely balanced with Yamaya’s jovial statements in the outer movements. The Amoroso offers another sensitive point of departure. The players place the mordents and trills on every line with utmost care.

Hagen’s Sonata in G major showcases the players in equally spirited moments. Bright arpeggios and fanfares convey the ebullience of the opening Allegro and concluding Vivace. The central movement brings lush contrast.

Though originally scored for violin and lute, Paul Charles Durant’s Duetto in G minor is well-suited to the lute-mandolino combination. Both musicians revel in the ornamental figures reminiscent of the dance music of the era. Schneiderman’s lute supplies weighty bass to Yamaya’s singing mandolino line, and the two deftly navigate the sudden shifts in tonality. The concluding Menuet brings equal parts delicacy and brooding intensity.

Silvius Leopold Weiss’s Ciacona offers the album’s greatest sense of mystery. The work originated as a movement in the composer’s Sonata in G minor, contained in the so-called London manuscript, a major source of Weiss’s music. Schneiderman and Yamaya reveal every curve and flourish of the work’s melody. Lute phrases flow smoothly into the mandolino line, making the score, much like the rest of this recording, a true conversation among friends.

Aaron Keebaugh has published articles in The Musical Times, Corymbus, and The Classical Review, for which he serves as Boston critic.