by Karen Cook

Published May 11, 2020

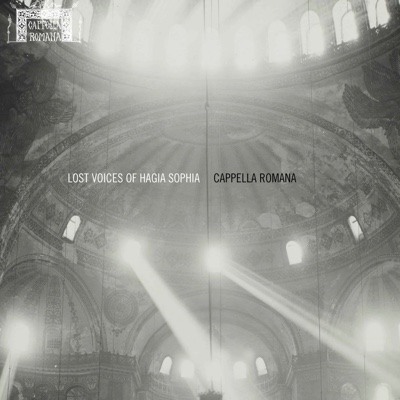

Lost Voices of Hagia Sophia: Medieval Byzantine Chant. Cappella Romana. CR420-CDBR. Audio CD & Audio Blu-Ray with documentary film.

Until the 16th century, Hagia Sophia was the largest cathedral in the world. Built in Constantinople in 537, it survives today as one of the greatest examples of Byzantine architecture, although it is no longer a house of worship; since 1935, it has been a museum.

While the adhan rings out twice a day from the building’s minarets, Hagia Sophia’s interior is a strictly secular space. Thanks to the wonders of modern technology and painstaking work of two college professors, however, it is possible to imagine what a medieval Byzantine service might have sounded like. Bissera Pentcheva, a professor of art history, and Jonathan Abel, a consulting professor at the Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics, co-direct the interdisciplinary Icons of Sound project at Stanford University. Utilizing the sounds of balloons popping in the interior space, they constructed an acoustical filter that could be applied to recordings and even performances.

While the adhan rings out twice a day from the building’s minarets, Hagia Sophia’s interior is a strictly secular space. Thanks to the wonders of modern technology and painstaking work of two college professors, however, it is possible to imagine what a medieval Byzantine service might have sounded like. Bissera Pentcheva, a professor of art history, and Jonathan Abel, a consulting professor at the Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics, co-direct the interdisciplinary Icons of Sound project at Stanford University. Utilizing the sounds of balloons popping in the interior space, they constructed an acoustical filter that could be applied to recordings and even performances.

The music on this album belongs to the Feast of the Holy Cross and is performed by Cappella Romana, an ensemble in Portland, OR, whose specialization in early Christian music made them an integral part of this project from its earliest days. The antiphons, psalms, and hymns are all monophonic, with textural and timbral contrasts wrought in the interplay between soloists and full ensemble and the alternation between lower and higher voices; common to Byzantine traditions, the ensemble frequently adds an ison, or drone.

Hagia Sophia is gigantic — big enough to hold 16,000 people and with a resultant reverberation time of more than five times as long as a modern concert hall. The singers must therefore significantly elongate words and phrases, as intoning words quickly would cause them to be all but lost. The prolonged phrases flow over each other in layers and waves, collecting and resonating in the dome. Listen to this sonic accumulation at the beginning of Psalm 140 and notice how it gradually dissolves into the higher voices; at the end, furthermore, the sound reverberates for nearly 12 seconds after the ensemble stops. The dome is particularly sensitive to higher frequencies, as in the single female voice at the beginning of the Prokeimenon.

The drones exacerbate this accumulation, blurring lines between phrases and creating a sense of sonic stasis, as in the last choral portion of the Cherubic Hymn. In many cases, the meaning of the text is also blurred, linking this music to the metaphor of divinity as light and water. The dome catches the sound like ascending breath and sends it showering back down like a sonic waterfall. The ensemble’s sound is rich and radiant, the sonic equivalent of the gold leaf that dominated the iconography of this tradition. They sound like light filtering through stained glass, glinting off of tiny dust particles as they float away. I wonder how the acoustical space might differ if it also recreated the building full of worshipers.

According to the Icons of Sound project, “Lost Voices of Hagia Sophia is the first vocal album in the world to be recorded entirely in live virtual acoustics.” The two-disc set includes a 24-minute documentary that explains the building and the project. The liner notes are incredibly detailed, replete with bibliographies, high-quality images, and musical examples. For the novelty of its digital recording process, attempts at historical recreation, and preservation of this repertoire, the album would be worth hearing. The quality of its musical creation, however, cements it.

Karen Cook specializes in the music, theory, and notation of the late medieval and early Renaissance periods. She is assistant professor of music at the University of Hartford in Connecticut.