by

Published July 29, 2019

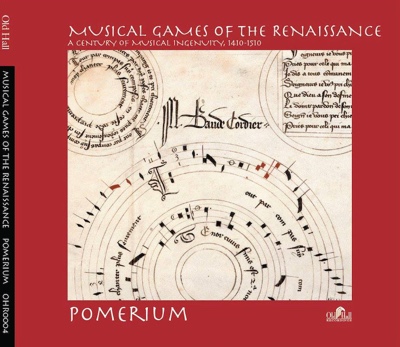

Musical Games of the Renaissance: A Century of Musical Ingenuity, 1410-1510

Pomerium

Old Hall OHR0004

By Karen Cook

Anyone privileged enough to have spent any time at the Met Cloisters in New York City will already know just what a treasure trove it is, full of gorgeous historical artifacts, thoughtfully arranged to highlight different aspects of life in the past. In 2016, one such exhibit comprised hand-painted playing cards, which were a source of both entertainment and art. To complement this unique display, the ensemble Pomerium performed a concert of Renaissance music showcasing musical games and puzzles. That concert became their latest recording, which will be available soon from the ensemble’s website and Amazon.com.

Pomerium is here the curator of their own musical exhibit, one that demonstrates some of the ways in which late Medieval and Renaissance composers engaged with what musicologist Katelijne Schiltz calls “riddle culture” — the fascination in Renaissance society with games to stimulate the intellect and to entertain. Such riddles in music could be musical or textual, formed by quotation or made through notation, or any combination of the above. (For those interested in such things, Schiltz’s recent book, Music and Riddle Culture in the Renaissance, is a fantastic resource.) The album features 11 tracks, each of which demonstrates a different kind of approach to musical games.

Pomerium is here the curator of their own musical exhibit, one that demonstrates some of the ways in which late Medieval and Renaissance composers engaged with what musicologist Katelijne Schiltz calls “riddle culture” — the fascination in Renaissance society with games to stimulate the intellect and to entertain. Such riddles in music could be musical or textual, formed by quotation or made through notation, or any combination of the above. (For those interested in such things, Schiltz’s recent book, Music and Riddle Culture in the Renaissance, is a fantastic resource.) The album features 11 tracks, each of which demonstrates a different kind of approach to musical games.

The clever reuse of pre-existing music was perhaps one of the most widespread of musical practices, whether one might consider it a game or not. The album begins with the beautiful antiphon “Argentum et aurum,” followed by two movements of the Mass built on it by Heinrich Isaac. But quotation is not Isaac’s only trick; he sets the chant at different rhythmic speeds, syncopates some voices, and in fascinatingly minimalist fashion, each voice of the first “Kyrie” sings only one type of duration (the uppermost voice, for example, gets to sing only dotted breves). Later, three different works borrow the famous “L’homme armé” tune: first, the polytextual rondeau “Il sera par vous conbatu/L’homme armé,” likely by Du Fay, followed by movements of the Mass by Ockeghem and the Missa L’homme armé sexti toni by Josquin.

Two other works are shaped in different ways by proportions. Busnoys celebrated his teacher Ockeghem in the motet In hydraulis, for which both the pitch and rhythmic durations are structured by Pythagorean proportions. The Sanctus of Josquin’s Missa Di dadi, on the other hand, has a pair of dice printed in the margins of the work that tell the performer what level of augmentation certain note values should have. (And for anyone confused by such a canon, Petrucci also printed the resolution to the riddle.)

The last two works are the two famous “picture songs” by Baude Cordier, “Tout par compas” (in the shape of a circle) and “Belle, bonne, sage” (in the shape of a heart); both also contain other notational, proportional, and canonic complexities.

Active since 1972, Pomerium, led by Alexander Blachly, is certainly no stranger to these works, and it shows. Each is handled like an old friend, with warmth, understanding, and a sense of invitation. The larger works are lovely, but for me the real standouts are the ones for smaller ensemble: the two Baude Cordier songs, and especially the witty, gorgous “L’homme armé” rondeau. It’s a comfortable recording, gentle and solid.

Karen Cook specializes in the music, theory, and notation of the late medieval and early Renaissance periods. She is assistant professor of music at the University of Hartford in Connecticut.